Growth and Concentration Trends in the English-language Network Media Economy in Canada, 2000-2012

This is the fourth post in a series on the state of the media, telecom and internet industries in Canada. It focuses on the growth of and concentration trends in ten sectors of these industries in the predominantly English-language speaking regions of Canada from 2000 until 2012: wireline telecoms, mobile wireless, internet access, broadcast TV, pay and specialty TV, total television, radio, newspapers, magazines and online (see here, here and here for the last three posts in this series) (for a downloadable PDF version of this post please click here).

The data and methodology underpinning the analysis can be found at the following links: Media Industry Data, Sources and Explanatory Notes, English-language Media Economy, CR and HHI English Media, and the CMCR Project’s Methodology Primary.

The Growth of the English-Language Network Media Economy, 2000-2012.

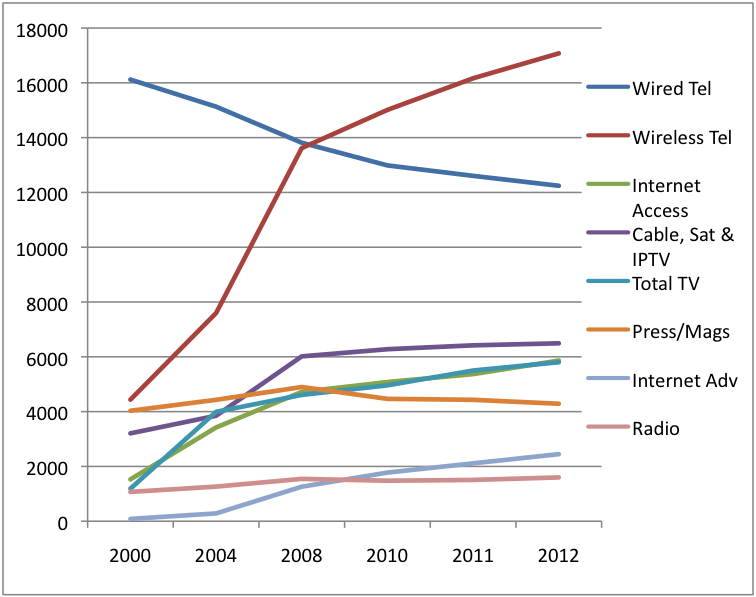

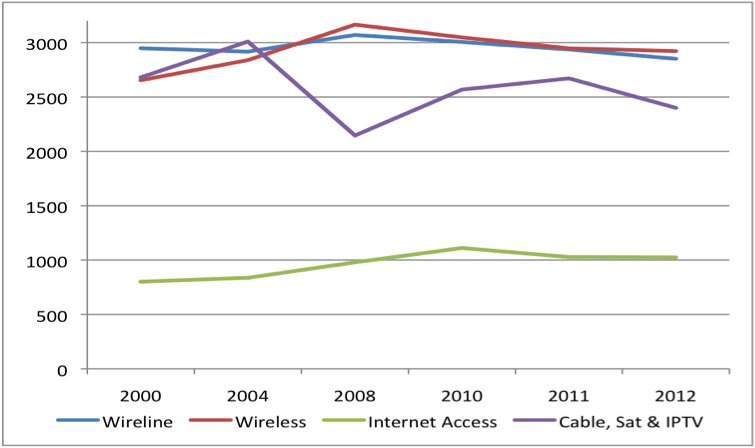

As with the rest of Canada, the English-language media economy expanded greatly from $31.7 billion in 2000 to $55.8 billion in 2012. Figure 1 below shows the trends over time.

Figure 1: The Growth of the English-Language Network Media Economy, 2000-2012 (Millions $)

Sources: English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

The fastest growing sectors of the English-language media economy have been internet advertising (2,782%), internet access (284%), mobile wireless services (284%), cable, satellite and IPTV (103%) and television (74%). The rapid growth of mobile wireless, internet access and cable, satellite and IPTV are leading to an ever more internet- and mobile wireless-centric media ecology, hence the notion of the network media ecology. For the most part, these trends are similar to patterns in the French-speaking regions of Canada.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, revenue for wireline telecoms has fallen by nearly a quarter since 2000. Newspaper and magazine revenues also seem to have peaked in 2008, and have fallen since then from $4.9 billion to $4.3 billion last year – a drop of 13%.

One crucial thing distinguishes English-language dailies from their French counterparts: paywalls. Two out of ten French-language dailies – Quebecor’s Le Journal de Montréal and Le Journal de Québec – have put up paywalls that limit readership to paid subscribers only (albeit with a soft cap that allows several free articles per month). For the English-language daily press, in contrast, twenty-four dailies accounting for two-thirds of average daily circulation are now behind paywalls.

All of the major English-language daily newspaper ownership groups have put paywalls into place over the last two years. Brunswick News (Irvings) led the charge in early 2011, followed by Postmedia (May 2011), Quebecor (September 2011), the Globe and Mail (October 2012) and the Toronto Star (August 2013). Many smaller papers are testing the waters as well (Glacier, Transcontinental and Halifax News). There are no hold-outs among the English-language daily newspapers equivalent to the role played by Power Corporation’s La Presse group of papers in Quebec.

While it is difficult to say exactly what accounts for this contrast, the fact that the CBC plays a much smaller role in English-language regions of the country compared to its place within the Quebec media landscape, probably explains much of it. As the fifth largest player with over 5% market share in Quebec, Radio Canada/CBC has maintained a large place for the public service model of news within the French-media ecology, whereas the CBC’s seventh place rank and two percent share of the English-language market means that it is correspondingly easier to carve out a near universal role for the commercial news model (see Picard and Toughill). Recent statements by the Globe and Mail about its target audience being households with more than $100,000 in income demonstrate exactly the kind of market failure that makes news a public good to begin with.

Radio still constitutes an important medium within the media ecology and actually grew significantly from 2000 to 2012, with revenues rising from $1070 million to $1,600 million. While revenues dropped for the two years following the financial crisis of 2008, the medium appears to be more resilient than many might have once thought, with revenues increasing ever since and reaching an all-time high last year – a pattern that mirrors trends worldwide.

As I have pointed out many times, the economic fate of the media hinges tightly on the state of the economy in general (see Picard, Garnham, Miege). This can be seen in Figure 1, which shows how the growth of several media flat-lined, declined and sometimes even dropped steeply after the onset of the “great financial crisis. Even fast growing segments like mobile wireless, internet access and total TV were not immune to this, while growth for cable, satellite and IPTV tapered off considerably.

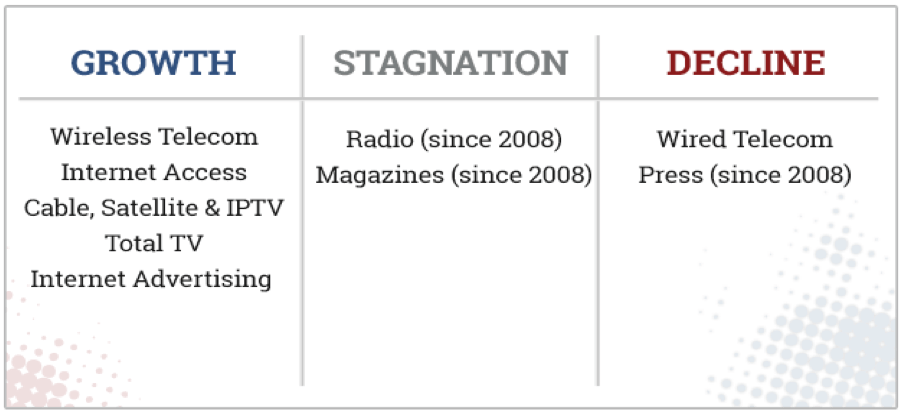

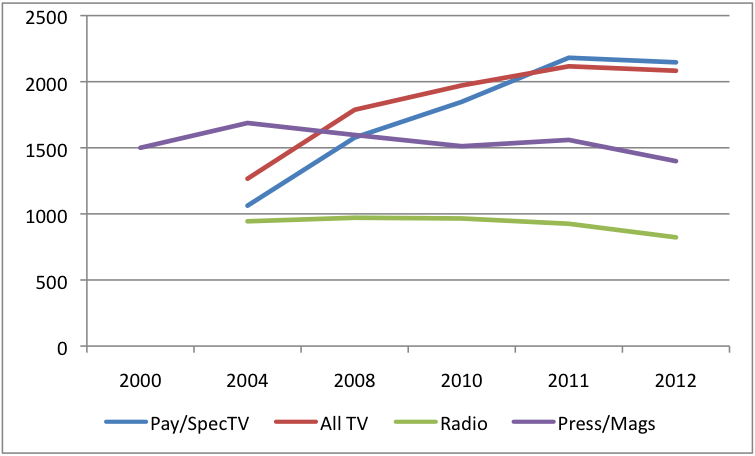

Figure 2 below gives a snapshot of the patterns of growth, stagnation and decline that have taken place within different media sectors since 2000.

Figure 2: Growth, Stagnation and Decline in the English-language Media Economy, 2000-2012.

Leading Telecoms, Media and Internet Companies in the English-Language Media Economy

The following paragraphs shift gears to look at the biggest media, telecoms and internet companies in the English-language media. Figure 1 sets the baseline by ranking the sixteen largest media, internet and telecom companies in these areas based on revenues and market share.

Figure 3: Leading Media, Internet and Telecoms Companies in English-Language Markets, 2012.

[visualizer id=”842″]

Sources: Media Industry Data, English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

As Figure 3 shows, Bell is the biggest player by a significant stretch, accounting for just under a quarter of all revenue. In Quebec, it was also the largest player, with an even larger one-third share across the French-language mediascape. It’s share of the national market is 28%.

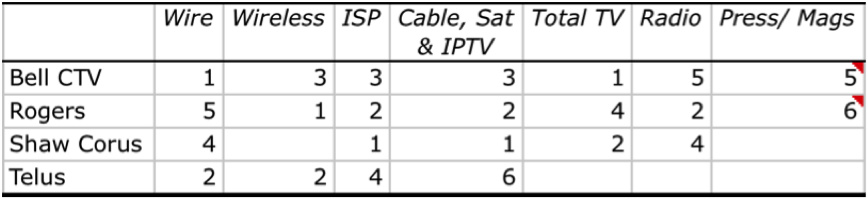

The two biggest companies – Bell and Rogers — account for 43% of all revenues; the “big four” for 70%: Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Telus. Three of these four companies — Bell, Rogers and Shaw — are vertically-integrated giants, and their reach, as Figure 1 shows, stretches across the sweep of the English-language mediascape.

Quebecor – the fourth biggest media conglomerate in Canada, hardly registers at all, ranking 13th with one percent share of revenues. Its dominance is limited to Quebec. Telus is not vertically-integrated at all, eschewing the idea that telephone companies need to own content to be effective players within the network media industries.

Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Telus’ control over communications infrastructure (content delivery) is the fulcrum of their business. Given the massively larger scale of these sectors relative to media content it is not surprising that these four firms rank at the top of the list. Their stakes in content media, while extensive, are modest; Telus is not in the content business at all beyond acquiring rights for its IPTV service, Optik TV and mobile TV.

As Figure 4 shows, between two-thirds and 100 percent of the big four’s business comes from control over connectivity and content delivery rather than content creation.

Figure 4: Content Delivery versus Content Creation

[visualizer id=”857″]

Content media are but ornaments on the carrier’s organizational structure, but they are being used to drive the take-up of mobile wireless services, broadband internet as well as cable, satellite and IPTV services, as telecom and internet gear makers like Sandvine and Cisco, and the International Federation of Phonographic Industries all observe. Illustrating this point, half the advertised roster of Bell’s Mobile TV service is filled with tv networks and specialty tv channels it owns: CTV, CTV News Channel, CTV Two, Business News Network, Comedy Network, Comedy Time, MTV, NBA TV, NHL Centre Ice, RDI, RDS, RDS2 and TSN, TSN2. Whether it ties this control over content and the means of delivering it to our doorsteps and into the palms of our hands in ways that confer preferential benefits on its own services at the expense of other content media and platform media providers and, ultimately, users, is an open question that merits further investigation.

While Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Telus tower over their peers, a dozen or so smaller entities fill out the field: MTS, Google, CBC, Torstar, SaskTel, Cogeco, Postmedia, Eastlink, Quebecor, Astral (before it was acquired by Bell in 2013), the Globe and Mail as well as newspaper and magazine publisher Transcontinental. Several things stand out from the list.

First, these companies’ revenues and market shares are less than a tenth of the corresponding figures for the big four. Second, second-tier firms, except Quebecor, are either in the content delivery business or the business of making content, but not both. In other words, they are not vertically-integrated, and depending upon which side they stand, this leaves them vulnerable to the three vertically-integrated goliaths when it comes to gaining access to either content, carriage or audiences, hence the interminable disputes over access to all three resources (see here, here, here, here, here and here for a sample of such disputes).

Third, with estimated revenue of $1,274 million from English-language markets in 2012, Google is a very big player and ranks sixth on the list. Facebook and Netflix, on the other hand, rank 17th and 18th on the list, based on estimated revenues of $182.3 and $114.2 million, respectively, and market shares of .2 and .3 percent. They are not big players on the Canadian mediascape.

The CBC still plays a significant role in English language markets, but it is steadily losing ground. At the outset of the 21st century, it accounted for about 30% of all TV revenue; today that number has been cut in half. Today, Bell and Shaw stand where the CBC stood a dozen years ago, with revenues and market shares nearly double those of the CBC.

In radio the CBC has slipped precipitously. Whereas it stood out within the field in 2004, by 2012 it was on an equal footing with Astral, Rogers and Shaw/Corus, each with between 11 and 14% market share. In English-language regions of the country, it is clear that public service core media have shrunk while the role of the market has expanded enormously.

Concentration in the English-language Network Media Economy, 2000-2012

Beyond the individual companies and their ranking, the most notable point with respect to the English-language media is that concentration levels are lower than in Quebec. While the HHI across all segments of the media combined in Quebec is at the moderate end of the scale at 1,800, in English-language markets it is 1,300 and at the low end of the scale, when we take the media as one large undifferentiated whole.

That, however, is the endpoint of analysis rather than the starting point, and it is essential to climb down from this view from the tree-tops to examine things sector-by-sector and then by broader categories (i.e platform media, content media, online media) before arriving at conclusions for the network media economy as a whole. And it should also be noted that while the HHI score is at the low end of the scale for the network media, the CR4 is not; the “big four” accounted for 70% of all revenues in 2012, as noted earlier – the same level as in French-language markets.

While Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Telus are top-ranked players in many of the sectors they operate in, none are dominant in all sectors. Table 1 below illustrates the point.

Table 1: Rankings of the Big Four by Media

The Platform Media Industries

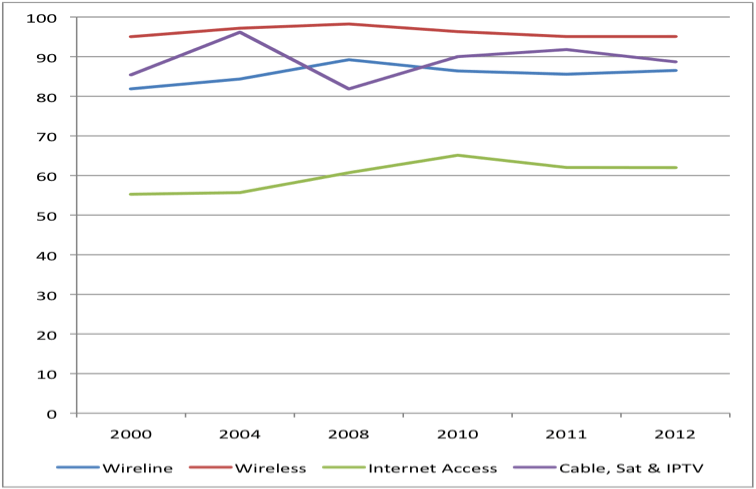

Figures 5 and 6, below, depicts the trends with respect to concentration levels over time for the platform media industries within the English-language media economy based on Concentration Ratios (CR4) and the Herfindhahl – Hirschman Index (HHI) (see methodology review in the second post in this series and the CMCR project’s methodology primer). Unlike the French-language media sectors assessed in the last post, the results are more mixed.

Figure 5: CR4 Scores for the Platform Media Industries in the English-language Media Economy, 2000-2012

Sources: CMCR Project CR and HHI English-language Media.

Figure 6: HHI Scores for the Platform Media Industries in the English-language Media Economy, 2000-2012

Sources: CMCR Project CR and HHI English-language Media.

As Figure 5 shows, all of the English-language platform media industries, except internet access, are very concentrated on the basis of the CR4 measure. Indeed, using the CR4 measure, concentration in each of these areas is similar to levels in Quebec, except for internet access, which is less concentrated in English-language parts of the country than in Quebec. While there has been some fluctuation over time, and a recent dip for wireless and cable, satellite and IPTV providers, there is no long term, significant decline concentration levels across the platform media industries.

The HHI measure provides a more discriminating view, indicating that wireline and wireless are firmly within the ‘highly concentrated’ range, while cable, satellite and IPTV fell just under the threshold for that designation. In general, concentration in each of these sectors rose in the early 2000s, peaked between 2004 and 2008, and drift downward slowly thereafter. Every segment of the platform media industries, except wireless, is significantly less concentrated than in Quebec.

The first thing to note with respect to mobile wireless service is that is the most concentrated of all sectors reviewed. Second, the English-language market is more concentrated than in Quebec, with the recent downward drift slower in English-language markets than in French-language ones. The most important point in both cases is that concentration is and always has been “astonishingly high”, as Eli Noam has recently noted in relation to trends around the world.

New entrant’s – Wind, Mobilicity and Public – have gained ground since entering in 2008, but they do not pose a challenge similar to Quebecor/Videotron in Quebec. As a result, Rogers (37%), Telus (29%) and Bell (26%) still dominate English-language markets, with 95% of wireless revenues. An HHI score of 2922 underscores the key point: concentration remains firmly at the upper ends of the scale.

Internet access, in contrast, is the least concentrated of the platform media and un-concentrated by the standards of the HHI, with a score of 1024 and only modestly so by the criteria of the CR method. Concentration levels rose steadily during the first decade of the 21st century but remained low in comparison to other segments of the platform media industries. They have also modestly declined since 2010.

However, the reality on the ground is that when we look closely at the local level, 93% of residential internet users subscribe either to an incumbent cable or telecom company, according to the CRTC ‘s Communication Monitoring Report, pp. 143-144). In other words, seen from afar, internet access looks remarkably competitive, but up close, it is effectively a duopoly.

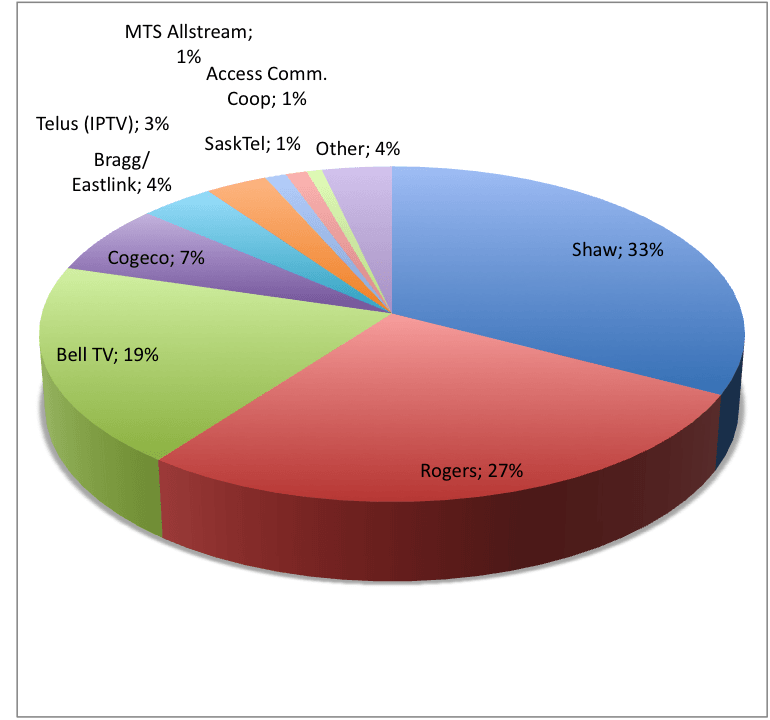

In terms of broadcast distribution markets (BDUs), IPTV services have steadily grown to become more significant rivals to the cable and satellite companies. CR4 and HHI scores have fallen as result since reaching their all time high in 2004, but still remain towards the high end of the scale with a CR4 of 88% and an HHI of 2400 — just beneath the threshold for highly concentrated markets.

Figure 7 below shows the market share and relative size of each of the main BDU players. With 79% of BDU revenues between them, Shaw, Rogers and Bell account for the lion’s share of the industry, while Cogeco, Eastlink and Telus, each with 3-7% market share, fill out much of the rest.

Figure 7: Cable, DTH & IPTV English-Language Market Share, 2012

Sources: English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

The Content Media Industries

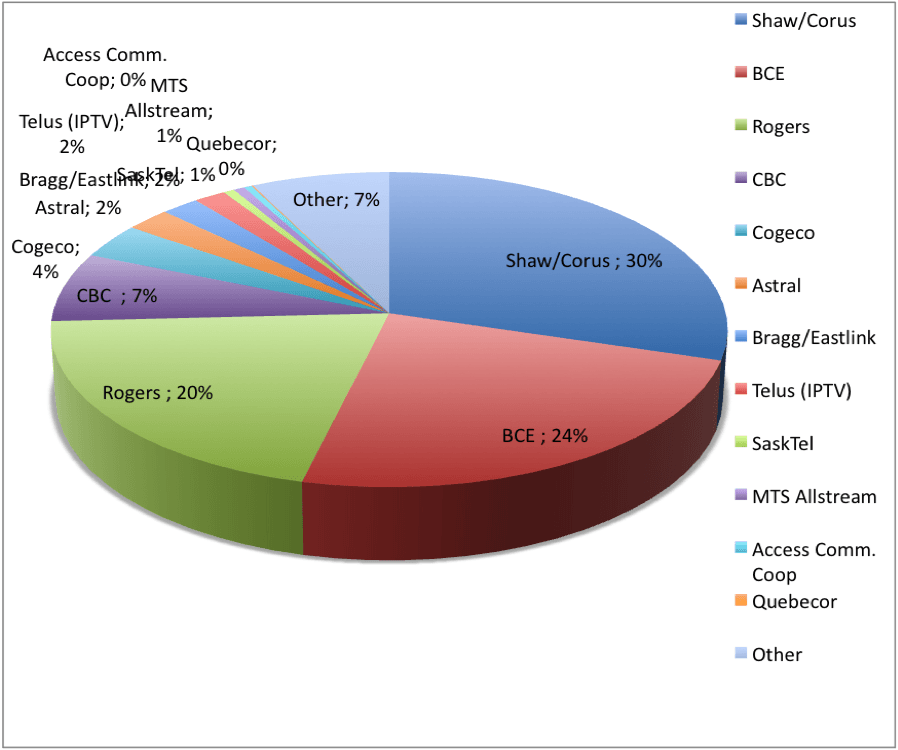

The big three – Shaw (Corus), Bell and Rogers – not only dominate the BDU side of the television industry, but the content side as well, although here it is becoming clearer over time that some clear blue water is opening up between Bell and Shaw (Corus), on the one side, and the more modest scale of Rogers, on the other, when it comes to TV holdings. I will return to explore this point further below but for now the main point to made is that, collectively, the big three control three-quarters of revenues across the entire TV landscape, i.e. distribution + broadcast TV and pay and specialty TV channels. Figure 8 illustrates the point.

Figure 8: Vertically-Integrated BDUs and Total Television by English-Language Market Share, 2012

Sources: English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

The total English-language television market – excluding the BDU side of things – needs to take account of a crucial fact that has crystallized more clearly in the past few years: the extent to which just two firms – Bell and Shaw – dominate the scene, with Rogers and the CBC falling ever further into their shadow with the passing of time and further consolidation.

Combined, Bell and Shaw controlled 57% of total TV revenues in 2012 before Bell acquired Astral Media, the fifth largest TV company in English language markets. That figure will climb closer to two-thirds once the effects of the Bell-Astral deal become reality in the revenues for 2013 – a point that will be dealt with more fully in next year’s version of this post.

The extent to which Bell and Shaw now stand at the commanding heights of English-language TV markets can be gleaned from a quick reprisal of their holdings. Thus, Shaw’s acquisition of Global TV and a slew of channels from bankrupt Canwest in 2010 gave Shaw/Corus a dozen conventional TV stations that comprise the Global TV network, additional broadcast stations in Oshawa, Peterborough and Kingston (Channel 12, CHEX TV, and CKWS TV, respectively) and fifty-one pay and specialty channels (Shaw and Corus Annual Reports). It’s share of total TV revenues? 27.3%.

Bell’s re-entry into the field after re-acquiring CTV in 2011 created an even larger entity with twenty-eight broadcast tv stations and thirty three specialty and pay tv stations (or forty after the acquisition of Astral). Bell’s 30% share of all TV revenue in 2012 ranked it as the largest TV provider in the country. Its take-over, in a joint-venture with Rogers, of Maple Leaf Sports Entertainment (MLSE) and a roster of sports channels – NBA TV, LeafTV, GolTV, etc. – with the Competition Bureau and CRTC’s blessing last year only compounds the trend.

By comparison, CBC and Rogers are the distant third and fourth tv operators, with 15.6% and 13% share of total tv revenues – roughly half the scale of Bell and Shaw. The CBC had 5 cable TV channels in 2012, while Rogers had a dozen – again, paling in comparison to Bell and Shaw, i.e. 17 in total versus 90+ for Shaw and Bell.

The comparison of these four entities within just the pay and specialty tv domain is especially interesting because, first, this is one of the fastest growing domains of the media economy and, second, because Bell and Shaw’s respective stranglehold is greater here than in either broadcast TV or the TV market as a whole. In 2012, Shaw was the biggest player in the pay and specialty channel domain with 33% market share, while Bell followed close behind with 28%. Together, the two accounted for 61% of all revenues. This looks more like a duopoly then either competition or any kind of reference to the big four that lumps these two goliaths together with Rogers, the CBC or, for that matter, Quebecor.

Bell and Shaw’s respective share of the pay and specialty TV market will reach new heights in 2013 on account of the Bell Astral deal. Shaw will account for 35% of the market, Bell 34%. With just under 70% share of the specialty and pay TV market between them, this is effectively a duopoly. This is why, for instance, Rogers was not signing from the same hymn sheet as Bell at the Bell Astral hearings or the vertical integration hearings in 2011. Bell and Shaw, however, sang koombaya together on both occasions as everybody else receded from view.

In short, the TV marketplace is bifurcating, with Bell and Shaw at the apex, followed far behind by two mid-size players, Rogers and the CBC, and a smattering of small entities scattered after that: APTN, Blue Ant, CHEK TV, Pelmorex, Fairchild, and so forth. In sum, the wave of consolidation blessed by the Competition Bureau and the CRTC stand as testaments to diversity denied. Canadians and the future evolution of the network media ecology in this country will labour under these conditions for years, probably decades, to come.

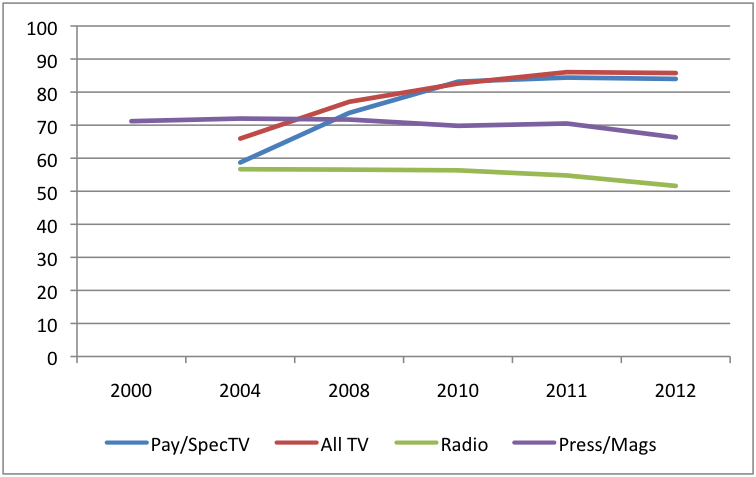

Before turning to a quick discussion of radio and then newspapers and magazine to complete this post, I want to depict the trends for the content media across time on the basis of both the CR4 and HHI scales. Figures 9 and 10 depict the trends.

Figure 9: CR Scores for Content Media in the English-language Media Economy, 2000-2012

Sources: English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

Figure 10: HHI Scores for Conent Media in the English-language Media Economy, 2000-2012

Sources: English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

Sources: English-language Media Economy, Sources and Explanatory Notes.

As has been the case at each other level of analysis, radio stands out as a clear contrast to trends in TV and in the platform media industries. The CR4 is at the low end of the spectrum, with the “big four” having just under 52% of the market between them: Astral (14.2%), Rogers (14.1%), CBC (12%) and Shaw (Corus) (11.4%).

Again, this will change in light of the Bell Astral deal with Bell catapulting from its fifth place ranking and 9.8% of the market to first place with 22% market share. Still, however, relative to the rest of the media, radio will remain relatively diverse.

This conclusion is illustrated more markedly on the HHI scale, with radio falling well into the un-concentrated zone with an HHI of 822.5. Moreover, the trend over the past half-decade has been steadily downwards – although that too is set to reverse in light of Bell’s take-over of Astral Media.

The last comments for this post are for the newspaper and magazine sectors which I treat together here, in contrast to separately in the Canada-wide analysis and hardly at all in the French-language media markets, mostly because of limits in the available data. Combining the two enlarges the size of the ‘relevant market’ and, consequently, diminishes the scale of specific players within either of these markets, nonetheless the analysis is still instructive.

The analysis shows several things. First, concentration levels are not high and have been falling for most of the past decade regardless of the measure used. Second, to the extent that we can speak of the “big four” press and magazine publishers, they are: Torstar (25%), Postmedia (19%), Quebecor (14%) and the Globe and Mail (8%). To be sure, while concentration levels are not sky high, that four entities account for more than two-thirds of all revenue does not seem worthy of celebration.

At the same time, however, this needs to be set against two other realities: first, both industries have fallen on hard times, newspapers more so than magazines, and as the big players stumble, they are losing market share and, in some cases, being broken up, with significant divestitures leading to the emergence of a stronger second tier of daily newspaper publishers: Transcontinental, Glacier, Black Press, notably. These entities now need to be put more firmly on the analytical radar screen.

Concluding Thoughts

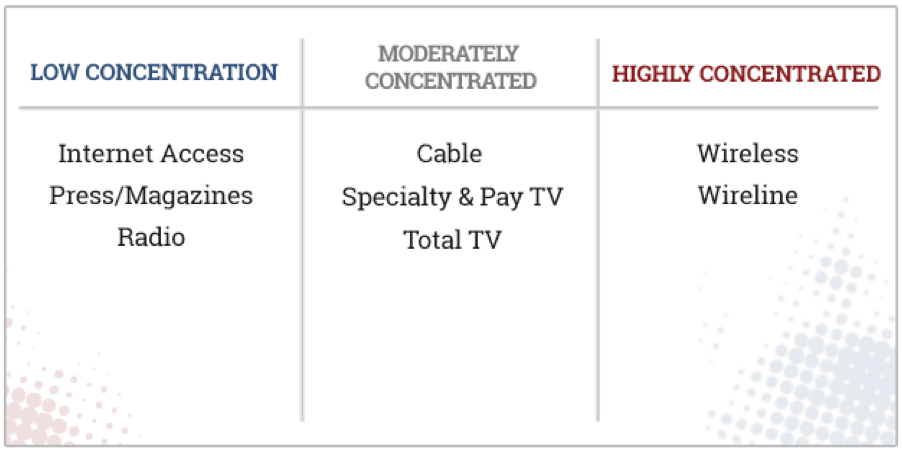

We can summarize the general results by sorting different sectors of the network media economy that rank low, moderate or high on the concentration scale according to the HHI. Figure 11 below does that.

Figure 11: Media Concentration Rankings on the Basis of HHI Scores, 2012

Over and above just giving a snapshot of where things stood as of 2012, we also need to distill the key developments over time. Several things stand out.

- the English-language media economy, like its Canada-wide and French-language counterparts, has grown greatly since 2000, although the course of development has been interrupted by economic instability since 2008. For a some sectors, notably daily newspapers, this may, with the passage of time, be seen as the tipping point in which they went into long-term decline, while for others conditions of prolonged stagnation seem to still be in play, i.e. radio and magazines;

- the media economy is increasingly internet- and wireless-centric, and mobile, but TV is still a large and significant driver within the network media ecology – carriage, not content, is king.

- Bell is the largest player in English-language markets with roughly one quarter of all revenues across a wide swathe of media, followed by Rogers, Telus and Shaw.

- the media in English-speaking regions of Canada are less concentrated than in Quebec, except for mobile wireless services;

- high levels of concentration persist across most platform media industries: wireless, wireline and falling just beneath the cut-off point, cable, satellite and IPTV services. Internet access is a partial exception when measured regionally or nationally, but not locally;

- an emerging duopoly is taking shape within the TV landscape, with Bell and Shaw currently accounting for 61% of revenues in the specialty and pay TV universe. This figure is set to rise to just under 70% once Bell’s acquisition of Astral and divestiture of several of that entity’s TV channels to Shaw (Corus) sets in. The CBC and Rogers lag far behind, with a combined market share between them much less than half the share held by Bell and Shaw;

- as a result of these trends, regulatory battles over access to the three essential resources of the media economy – carriage, content, audience attention – will persist into the future; whether regulators will rise to the occasion any better than they have to date is an open question;

- Internet access, radio, newspapers and magazines stand out as exceptions to these general trends and as media in which greater diversity and some modest competition prevails.

Next post: How do concentration levels and trends in Canada stack-up by international standards?