The Growth of the Network Media Economy in Canada, 1984-2017 (UPDATED)

The workbook and reports were revised in early January 2019 to replace estimated revenue values for the mobile wireless, internet access and internet advertising markets with published final revenue figures from the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) on December 21, 2018 and by the Internet Advertising Bureau of Canada on December 10, 2018.

Download a PDF of this report here.

The Canadian Media Concentration Research project is directed by Professor Dwayne Winseck, School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University. The project is funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and aims to develop a comprehensive, systematic and long-term analysis of the media, internet and telecom industries in Canada to better inform public and policy-related discussions about these issues.

Professor Winseck can be reached at either dwayne.winseck@carleton.ca or 613 769-7587 (mobile).

Open Access to CMCR Project Data

CMCR Project data can be freely downloaded and used under Creative Commons licensing arrangements for non-commercial purposes with proper attribution and in accordance with the ShareAlike principles set out in the International License 4.0. Explicit, written permission is required for any other use that does not follow these principles. Our data sets are available for download here. They are also available through the Dataverse, a publicly-accessible repository of scholarly works created and maintained by a consortium of Canadian universities. All works and datasets deposited in Dataverse are given a permanent DOI, so as to not be lost when a website becomes no longer available—a form of “dead media”.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Ben Klass, a Ph.D. student at the School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University, Lianrui Jia, a Ph.D student in the York Ryerson Joint Graduate Program in Communication and Culture and Han Xiaofei, also in the Ph.D. program at the School of Journalism and Communication, Carleton University. They helped enormously with the data collection and preparation of this report. Ben wrote key aspects of the wireless section. Sabrina Wilkinson, a graduate of the School of Journalism and Communication at Carleton University and currently doing her doctoral studies at Goldsmiths University in the United Kingdom, also offered valuable contributions to the sections on the news media. Agnes Malkinson, another Ph.D. student in the Media and Communication program at Carleton University, is responsible for the look and feel of the reports, and keeps the project’s database in good working order.

Executive Summary

Every year the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project puts out a series of reports on the state of the telecoms, internet, and media industries in Canada. This is the first installment in this year’s series.

The report examines the development of the media economy over the past thirty-three years. We do so by examining a dozen or so of the biggest telecoms, internet and media industries in Canada, based on revenue. These include: mobile wireless and wireline telecoms; internet access; cable, satellite & IPTV; broad- cast, specialty, pay and over-the-top TV; radio; newspapers; magazines; music; and internet advertising. We call the total

of these sectors “the network media economy”. Our method is simple: we begin by collecting, organizing, and making available stand-alone data for each media industry individually. We then group related, comparable industry sectors into three higher level categories: the “network media” (e.g. mobile wireless, internet access, broadcast distribution), the “content media” (e.g. televi- sion, newspapers, magazines, etc.) and “internet media” (e.g. in- ternet advertising, search, internet news sources). Ultimately, we combine them all together to get a bird’s-eye view of the network media economy. We call this the scaffolding approach.

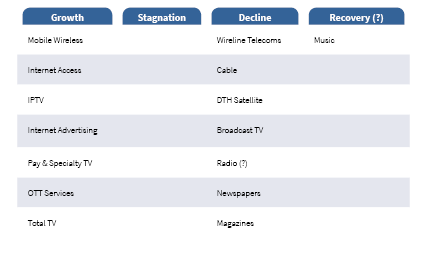

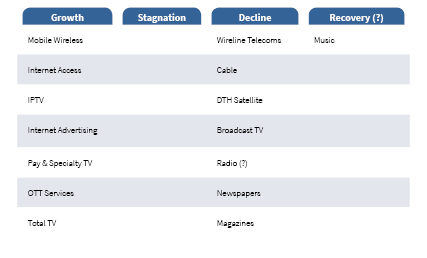

Why do we do this? Simply put, it helps us understand the state of the telecoms, internet and media industries in Canada. It helps us to see which of these industries are growing, which are stag- nating, which are in decline, and to identify those that appear to be recovering after years of misery. The following figure offers a high-level snapshot of where things stood at the end of the last year.

Table 1: The Growth, Stagnation, Decline and Recovery of Media within the Network Media Economy, 2017

Understanding the media environment also helps to focus attention on the pressing issues of the day. Communication and media scholars, for example, typically emphasize the importance of content media and accordingly place a central focus on develop- ments in advertising-based media. Our analysis, however, suggests that “bandwidth,” “connectivity”, and media that we pay for either by subscription (e.g. internet access, mobile wireless service, pay and internet streaming TV services such as Crave, Netflix, Amazon Prime, etc) or directly (e.g. books, mobile phones, TV, etc.) are far more import- ant than is often assumed.

In fact, in terms of all of the sectors of the “network media economy” that we look at in this report, subscriber fees outstrip advertising dollars by a five-to-one ratio. Moreover, total advertising spending across all forms of media has been declining relative to the size of the overall economy for the last five to ten years, both in real dollar terms and on a per capita basis. This year’s report adds a new section and much expanded discussion that illustrates and analyzes the significance of the declining place of advertising rev- enue within the network media economy and the broader Canadian economy. It also draws out the implications of this for how we think about media and cultural policy in the age of an evermore internet- and mobile wireless centric media universe. This helps to inform consideration of the alleged impact of Google, Facebook and the internet more generally amidst such a critical but heretofore fundamental reality of the media economy.

The upshot of these observations is that focusing solely or primarily on advertising-based content media is akin to looking at the world through the wrong end of the telescope. For those who long to “repatriate” advertising dollars from Google and Face- book, such a strategy is like re-arranging the deck chairs on the titanic—that is, if the decline of advertising is really such a terrible thing after all. To be sure, advertising-sup-

ported media are undoubtedly facing tough times. But it would be misguided to take this singular problem as the basis for making diagnoses and policy recommendations that apply across the network media economy as a whole, as is all too common. Within this context, our work and reports can be seen as a plea to reset the hierarchy of intel- lectual and research priorities, and to match them with the increasingly broadband- and mobile-centric media universe, and one where “the pay-per media”, not advertis- ing-supported media, are the number one priority.

Our goal is also to bring a wealth of historically- and theoretically-informed empirical evidence to bear on contentious claims about the media industries. Within a context where the role of policy and regulators looms large, knowing both the details and the broad sweep of the network media economy allows us to make informed contributions to the debate from an independent standpoint. This is especially true this year given that reviews of the Telecommunications Act, the Broadcasting Act, the Copyright Mod- ernization Act and the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA) are now in full swing. In light of such realities we need the best, independent view of the landscape that we can get, and that is what we strive to do with our annual reviews and regular updates to our data sets (which are available freely to anyone). In short, doing this kind of research is about tooling up for the policy battles to come.

In these ongoing “battles over the institutional arrangements of the information econ- omy” (Benkler, 2006), our research is about contributing to results that benefit the citizens and businesses they affect. Our approach contrasts with that of the companies who stand to gain directly by influencing policy that impacts the bottom line; such rep- resentations are typically partial, and they are certainly designed to win policy battles rather than to offer rigorous and fair-minded analyses of the media world. Independent research like ours aims to bring balance to the record.

We view our efforts as all the more important given the vast difference in resources available for such endeavours. Consider, for example, that Bell maintains a stable of lawyers reputed to be forty or more deep, Telus and Rogers in the mid-twenties, and Quebecor more than a dozen—human resources that are in constant motion attempting to influence the outcome of relevant government policy and regulatory affairs. This ob- vious disparity weighs against the idea that we can totally balance the scales. Nonethe- less, there is much value in contributing what we know about the communications and media services and markets in Canada because increasingly they are the foundations upon which more and more of our economy, society, polity and daily life depend.

Moreover, a rising backlash against the growing dominance of global internet gi- ants—e.g. Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft and Netfix—has led to the revival of the antimonopoly movement in the US; it has put blackbox algorithms under greater regulatory scrutiny than ever; and it has raised probing questions about the compatibility between the kind of “surveillance capitalism” their activities portend, on the one hand, and people’s rights and security, and even the integrity of democracy, on the other. The feverish pitch of this backlash makes the kind of measured, independent research we present in this report more essential than ever.

The revelations in early 2018 that Cambridge Ana- lytical harvested personal information from 87 mil- lion Facebook users’ profiles—including 620,000 in Canada—and that that information was then used as part of questionable electoral campaign strate- gies and disinformation campaigns—i.e. the 2016 US presidential election, the Brexit referendum in the United Kingdom, elections in the Netherlands, Germany, Brazil and other countries around the world—has added a whole new dimension and sense of urgency to such concerns. Fundamental questions about whether the very business mod- els and extraordinary market power of internet giants such as Facebook and Google are inherently primed for such nefarious possibilities, regardless of their owners’ best intentions to connect the world and foster community, are now on the table like never before.

Questions are also being raised about whether these entities have, essentially, become too big to effectively govern—either through self-regulation or by government (see Standing Committee on Access to Information, Privacy and Ethics’ report as well as the Information Commissioners Office’s report). Indeed, the Canadian at the head of the Information Commissioner’s Office in the United Kingdom, Elizabeth Denham, now questions whether commercial business models based on the unlimited harvesting of personal data and brute market power are compatible with funda- mental privacy rights, personal data protection, and even the integrity of democratic elections, That Amazon, Facebook or Google could be bro- ken up just like AT&T was in 1984 is no longer a far-fetched idea (Khan, 2017; Vaidhyanathan, 2018; Wu, 2018). Indeed, the issue is no longer if the plat- forms and internet content will be regulated but when and how (see, for example, President Em- manuel Macron of France’s speech to the Internet Governance Forum in November 2018).

While some smell “blood in the water”, there is also a need to distinguish between tough regulatory remedies and being propelled over the edge of the cliff by a hyped up sense of moral panic. The rush to harness Facebook, Google, Twitter, and other in- ternet intermediaries to the tasks of cracking down on disinformation, mass piracy, counterfeit goods, the sex trade, terrorist propaganda, and so on, are all examples of real problems to be dealt with. But the remedies commonly proposed to address these problems–treating the platforms as publishers, broadcasters or media companies—could be worse than the ailment they seek to cure, and so care must be taken to properly understand the situation before blindly rushing to action.

As this report indicates, experience to date already shows that these companies tend to be ham-fist- ed when it comes to making refined judgements about art, sexuality, culture and context. The idea that they should take on content filtering and blocking efforts on their own or be dealt with by the state in the same way as traditional publishers, broadcasters or media companies, seems ill-fitting, and threatens to open the sluice gates to a never-ending list of self-seeking demands from special interests. Unless the rules governing such companies’ conduct arise from, and are guided by, duly constituted legal and democratic oversight by parliaments, the courts, or administrative agencies, such demands will likely make the “black box” nature of internet platforms even more opaque than they already are.

Ironically, labeling the internet companies as either publishers or broadcasters in order to imbue them with a greater sense of responsibility with respect to content moderation could bolster their claims that they are entitled to the highest stan- dards of free speech protection possible—at the expense of their users’ speech rights and other democratic fundamentals. Such an outcome would strengthen corporate rule while ignoring a funda- mental problem: governments’ failure to govern on behalf of their citizens. The upshot overall would be yet greater accumulations of ‘power without responsibility’.

Later in this report we will also suggest that, in- stead of the analogy to broadcasting or media companies, perhaps a better analogy is to banks? This is because, like banks, Google and Facebook, for example, are repositories of what many see as the main source of wealth in the digital economy: data. Perhaps they should also have, again, like banks, fiduciary obligations towards their users, including safe-guarding their data and personal privacy. Furthermore, just as banks are regulated by strong authorities and must undergo certified audits and report those to regulators, similar regulatory requirements would open up the “black box” containing the algorithms and other critical infrastructure that underpinning more and more of the economy, society and our day-to-day lives? And just as HSBC, for example, sets up branches in each country it operates—i.e. HSBC Canada, HSBC Mexico, etc.—so, too, might it be a good idea to re- quire Facebook and Google to establish a national branches where they operate.

To be clear, we are fully supportive of concerns regarding the scale of these companies, their clout, and the threats that they pose to the internet, de- mocracy and society in general. However, our anal- ysis suggests that a healthy amount of skepticism should meet claims that the internet hypergiants’ fortunes are being made solely off the backs of “content creators” and by cannibalizing the reve- nue that journalism and the music, movie, televi- sion and publishing industries need to survive as, for example, Jonathan Taplin’s polemic against the “vampire squids of Silicon Valley”, Move Fast and Break Things, asserts. Such sentiments have been embraced in Canada, where industry players and think tanks as well as the trade associations and labour unions that represent the “creative industries” vilify Google, Netflix and Facebook

for allegedly laying waste to Canadian media and culture (the Public Policy Forum’s Shattered Mir- ror and Democracy Divided reports exemplify the point; also see Winseck, 2017 for a critique of the first of the Shattered Mirror).

To help understand this tangled knot of issues we need to better appraise where the internet giants currently stand within Canada. Of course, we know that they loom large, but how large?

Our data show that the US-based internet giants may, in fact, be on a path to monopoly in some media and data markets. Indeed, the shift to the “mobile internet” has helped Google and Facebook to consolidate their strangle-hold on the $6.8 billion internet advertising market in Canada. They accounted for three-quarters of the internet advertising market by 2017, and over a third (~37%) of the $13.6 billion advertising spent across all media. This is critical to comprehending the bleak place that many advertising-based media now stand.

However, it is a fundamental error to generalize from the digital duopoly’s dominance of the in- ternet advertising market in Canada to the $81.2 billion network media economy as a whole. The same applies globally.

Treating developments in the advertising-based sectors as representative of the overall direction of the industry also obscures the reality that whilethe internet companies may be giants globally and on the basis of market capitalization, within coun- tries (Canada in particular), and on the basis of revenue, they continue to be outstripped by a large margin by the biggest national communications and media groups: e.g. Bell, Rogers, Shaw, Quebe- cor and Telus (the “big 5”). The Canadian situation is also unique insofar that all the main commercial

TV services are owned by telecoms companies and their operations span aspects of the network me- dia economy that go far beyond internet advertis- ing as well. Given this set of facts, while the im- pact of GAFAM is undoubtedly great, we must ask whether they really pose as much of a challenge to the network media economy in Canada as so many commentators assert? The answers to these and other questions have significant implications for how we understand the media and what we do about the very real problems that do exist, as our research shows.

To get a better sense of all the moving parts and how they intersect and overlap, we need to un- derstand the many media markets in which these and other companies operate and whether, sim- ply put, they are becoming bigger or smaller in terms of revenue and more or less profitable over time. The answers to those questions informs our understanding of how the entities that comprise the broad network media economy interact and sometimes compete with specific firms like Net- flix, Google and Facebook. In other words, the approach our research takes provides context that is crucial to developing an informed and holistic understanding of contemporary developments within and across the various sectors of the net- work media economy.

The answers to the questions posed above also have much to add when evaluating assertions that we should discard the regulatory and legal frame- works set down a quarter-of-a-century ago, when the internet was just a glimmer in a few people’s eyes, in order to unshackle Canadian players so that they can rise to the challenge posed by the internet hypergiants and the shift to what some refer to, amorphously, as “the digital media universe”.

All-in-all, the media’s place in the economy, society and our everyday lives is changing dra- matically and is now up for grabs in ways seldom seen. The stakes are high; they are not just about numbers, revenue, market shares, and economic trends, but what kind of communications and me- dia landscape we want and deserve, and how such a landscape fits within a democratic society. Some communication historians call times like these a “critical juncture”, or a “constitutive moment”, when decisions made will become embedded in technology, markets and institutions, and then press down on us, for a very long period of time thereafter, perhaps a century or more if the les- sons of “the industrial media age” offer any guide to the contemporary debates surrounding the “in- ternet” or “digital media age”. The CMCR Project does its best to engage with such realities in a bid to help secure the communication and media that we need and deserve.

Summary of key findings and insights

- The network media economy has more than quadrupled in size, from $19.4 billion in 1984 to

$81.2 billion last year.

- mobile wireless and internet access services continue to grow briskly, with revenues rising to

$25.8 billion and $11 billion, respectively, last year; while cable, IPTV and satellite TV con- tinued to slide to $8.5 billion—a decline from all-time highs of $8.9 billion four years earlier. Wireline revenues (e.g. revenues from “plain old telephone service”) continued their long- term fall to $13.1 billion in 2017.

- the adoption and use of wireline internet access is high in Canada relative to other OECD countries, but speeds are mediocre, prices high, data usages slightly below average, and data caps extensively used and set at low levels whereas in most countries that are compara- ble to Canada they are rare and the cost of exceeding them not as punishingly

- mobile wireless (i.e. the mobile internet) adoption in Canada ranks very poorly against other OECD countries. For example, Canada ranks a lowly 30th out of 36 OECD countries in terms of adoption—a drop in rank compared to other countries over the previous Canada also does not fare well in terms of mobile data use, either, ranking 27th out of 36 OECD countries surveyed with an average of 1.9 GB of mobile data usage per subscriber per month—well be- low, for example, Finland (15.5 GB), Austria (11.2GB), Denmark (5.7 GB), France (3.4GB) and the United States (3 GB).

- nearly one-in-three households in the lowest income quintile do not subscribe to a mobile wireless service, while only one-in-seven of those on the next rung up stand in the same po- sition. By contrast, mobile wireless service is nearly universal for the most well-off in

- the cost of media devices is plunging but the cost of communication services like broadband internet access, mobile phone and cable TV (including IPTV) continue to rise briskly relative to the consumer price

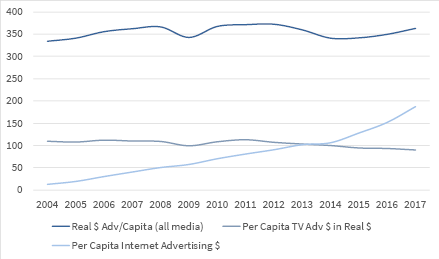

- advertising spending has been in decline in inflation-adjusted “real dollars”, on a per capita basis, relative to the media economy, and in relation to the gross domestic of Canada for the past half-decade or so, although last year there was a reversal in fortunes. Whether that will

continue, however, it is too early to tell. Last year’s reversal aside, however, on a per capita basis, it was $362 per person in 2017—down from $371 a half-decade earlier.

- TV advertising spending also peaked at $112 per capita in 2011 but fell to $86.2 last year in real dollar terms. Across the TV marketplace—broadcast TV, pay and specialty services, and streaming TV ser- vices—subscriber fees account for 62% of all revenue (excluding the CBC’s Parliamentary grant). TV remains a pillar of the internet- and mobile wireless-centric media ecology, but the ways in which it is accessed and paid for are

- advertising is in relative decline but internet advertising soared to an estimated $6.8 billion last year versus $5.5 billion the year

- Internet advertising is becoming more concentrated, with the top ten internet companies accounting for 85.2% of all revenue in 2017, up from 77% in

- Google and Facebook dominate the internet advertising market, with nearly three quarters of the market under their control in 2017—up from 69% a year

- Subscriber fees outstripped advertising revenue by more than 5:1 in 2017. The “pay-per media” (e.g. mobile phones, internet access, pay and streaming TV services) are vastly more significant in terms of sheer economic size than advertising-based media (e.g. broadcast TV, internet advertising, news- papers).

- Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw (Corus), Quebecor (Videotron), Google, Facebook, CBC, Cogeco and Sasktel are the ten largest communications and media companies in Canada by revenue, in that The “big 4” Canadian companies’ revenues are several times higher than the Canadian revenues of the US internet giants.

- The telcos in Canada own all the major TV services, except the CBC. This arrangement stands in contrast to those in the US, UK and most of Europe. This helps explain why broadcast TV and stand- alone internet streaming options have fared poorly in Canada relative to those

- While broadcasting TV in Canada is in dire straits, it is important to ask why conditions are especially bad in Canada relative to other countries where, while not thriving, broadcast TV is

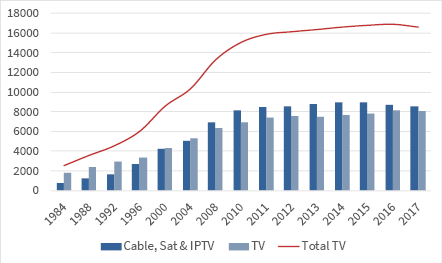

- The TV marketplace in Canada has and is thriving with fundamentally new pay TV sectors added to it over time, including the rapid growth of over-the-top streaming services Based on CMCR data, total TV revenues had soared to over $8 billion in 2017 and to an estimated $9.6 billion if the CRTC’s figures for streaming, transactional video-on-demand (TVOD) and ad-based video-on-demand (AVOD) services are used, although this report is skeptical of the value the Commission assigns to Netflix, Youtube and Apple’s iTunes.

- Netflix had an estimated year-over-year average of 6.6 million subscribers and $820.6 million i n Canadian revenue in It is now the fifth largest TV service operator in Canada, and bigger than Quebecor’s TV operations (not including cable). At year’s end, just less than half of all Canadian households subscribed to Netflix (~49%).

- Telus, Bell and SaskTel had nearly 2.8 million IPTV subscribers between them at the end of 2017 and accounted for roughly a quarter of all cable TV subscribers and revenues. Competition between the telcos’ and cable companies’ video distribution platforms has intensified in recent

- Cable “cord-cutting” is real but remains modest. Total subscribers fell from 11.5 million in 2012 to 10.7 million last Accounting for population growth, 76% of all households subscribed to a cable television service last year–down from 85.6% in 2011.

- Fibre-based broadband infrastructure is under-developed by international standards, and access for end-users is Penetration levels are roughly half the OECD average. Canada ranked 27th out of 36 OECD countries in 2017 in terms of fibre-to-the-doorstep—the internet infrastructure of the 21st Century.

- The CRTC’s actions over the past few years responded appropriately to reality and matched those of regulators in the EU and the FCC in the US—although this appears to be changing under the direction of the Commission’s new chair and as the regulatory framework in the US is hastily dismantled by the Trump administration’s appointed chair to the FCC, Ajit

- The impact of cord-cutting, Netflix, Google, on the “broadcasting system” is real but exaggerated. Framing these factors as threats to the “broadcasting system” biases how these issues are framed, and in so doing constrain the range of media and cultural policy options on the table and how they are discussed.

- Appeals to policy makers and the CRTC to adopt an “internet levy” and to require that ISPs and mo- bile operators selectively use data caps and zero-rating to promote Canadian content should be treat- ed skeptically in light of these

- Newspapers are in turmoil with revenue plunging from a high of $4.7 billion in 2008 to under $2.6 bil- lion last Laying the blame for this state of affairs at the feet of Google and Facebook is common but ignores how self-inflicted wounds and the decline in total advertising revenue, have contributed greatly to this state of affairs.

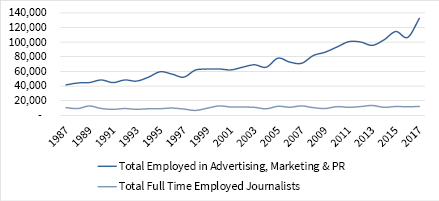

- The number of full-time journalists has grown modestly over the long run (i.e. since 1987) but stayed fairly steady at ~11,500 for the past five years. The ratio of public relations, advertising and marketing professionals to journalists, however, has soared from four-to-one in 1987 to eleven-to-one at

- Canadians consult a wide-range of “old” and “new” as well as “domestic” and “foreign” news sourc- es online: e.g. the CBC, Postmedia, Torstar, CTV, Globe and Mail, Huffington Post, CNN, the New York Times, Washington Post, The Guardian, the BBC, Yahoo!-ABC, etc. However, there are no “digital native” Canadian news organizations such as iPolitics on the list of the top 50 internet news sites visited by Canadians.

- The steady decline of advertising over the past half-decade or so reveals the fact that people have never paid the full-cost of a general news service. Such services have long been subsidized by wealthy patrons, advertising, or the public purse. It’s time to figure out who will pay what all over again, and while the “pay-per” model will pick up some of the slack, it won’t be enough and comes with the ad- ditional problem that it aggravates information

- Thus far, analogies to broadcasting, publishing and media companies have driven the agenda when it comes to proposing regulatory remedies to the dominance of digital platforms. This report suggests that we should think of them as being more like banks that store a new source of wealth—data, who have a fiduciary obligation to protect the sanctity of their users’ privacy, and whose complex machin- ery should be subject to regular and regulated audits to ensure accountability and that they operate in the public interest.

Current Developments and Debates

Every year for the past six years the CMCR Project has put out a series of re- ports on the state of the telecoms, internet and media industries in Canada (see 2016, 2015, 2014, 2013, 2012 and 2011). This report is the first install- ment in this year’s series.

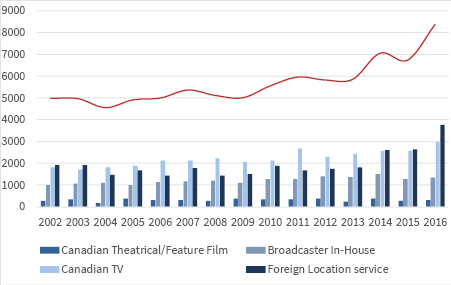

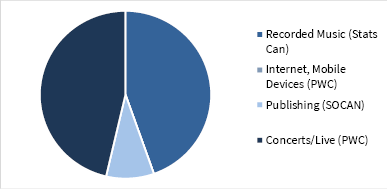

The report examines the development of the media economy since 1984, with the “media” defined broadly to include mobile wireless and wireline telecoms services; internet access; cable, satellite & IPTV; specialty and pay TV; broadcast TV; radio; newspapers; magazines; music; and internet adver- tising.Its aim is to get a good sense of how all the different sectors of the tele- coms-internet and media industries have developed over time, and how they fit together to form what we call “the network media economy”. It is also to determine which of these industries are growing, stagnating or in decline, while shining light on those that are showing signs of renewal, like the music industry. It also examines whether internet streaming services like Netflix, Crave and Spotify, and trends such as cord-cutting, are delivering lethal blows to established media or helping to expand the size and diversity of the media economy overall.

A key development identified in this report is the extent to which advertising-supported media (i.e. broadcast television, radio, newspapers and magazines) are being eclipsed by the “platform” and “pay-per” media industries (i.e. mobile wireless, wireless telecoms, ISPs, as well as cable, DTH and IPTV services). The “platform” segments of the media— the pipes, bandwidth and spectrum that people use to connect with one another, to media content, the internet, and so forth—accounted for just under three-quarters of all revenue generated within the network media economy by the end of 2017. The revenue of “pay-per” media that mainly rely on subscriptions and direct now outstrips that of advertising-based media, including internet advertising, by more than five-to-one.[1] In an increasingly internet- and mobile wireless-centric world, connectivity and subscriber fees, not content and advertising, are king (see Odlyzko).

The gap will likely grow over time because, while nominal advertising revenue for all media has inched upwards over the past decade, it fell on a per capita basis and in inflation-adjusted terms (see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook). This stagnation/slight decline is likely due to two factors: anemic and unsteady economic growth since the financial crisis of 2008, and that internet advertising displays very strong economies of scale. These strong economies of scale are driving consolidation in the internet advertising market on a national and global scale and having devastating effects on traditional advertising-based media. Local, regional, or national media outfits that lack the economies of scale and the ability to measure and target advertising as precisely enjoyed by the global internet companies, and thus find themselves at a structural dis- advantage when it comes to competition for advertising dollars (Hindman, 2018).

Given these realities, it is not surprising to learn that the top ten internet companies’ combined share of online advertising revenue grew from ~77% in 2009 to 85.2% in 2017. Google and Facebook alone accounted for an estimated 75% of the $6.8 billion in inter- net advertising revenue last year. This was a very sizeable increase from their estimated two-thirds share of the internet advertising market the year before.2 Both companies have taken advantage of the rise of mobile internet to consolidate their duopolistic con- trol over the internet advertising market—a point that we will take up in further detail in the next report. Of decisive importance is the fact that the “digital duopoly” now controls more than a third of the $13.6 billion in advertising spending across all media in Cana- da—a scale that has soared rapidly in recent years. The fact that Google and Facebook are consolidating their grip over a slowly shrinking pool of advertising revenue has also sharpened and intensified the conflict between them and other media companies that still rely on advertising to survive.

Many media companies, trade associations, and trade unions representing the creative industries have called for a levy to be applied to internet service providers (ISPs) and mobile wireless carriers to offset these losses.[3] The Creative Canada Policy Framework released by the Department of Canadian Heritage in September 2017, however, rejected the idea. While the aim of supporting journalism and original audiovisual media content is laudable, using an ISP levy to do so deflects attention away from the decline in advertising revenue and the broader economics of internet advertising. It also ignores the fact that people have never directly paid the full cost for media that have “public good” characteristics and that such consumption has long been subsidized by either advertising, government funds or wealthy patrons.

The ISP levy is based on policy tools that have been designed within the context of a cable television-centric “broadcasting system” over the past fifty years. It attempts to take policy tools built for a single purposes network—cable TV—and to apply them to general-purpose internet access infrastructures. One major consequence of the early approach, however, was that the potential for cable systems to be developed as multi-purpose common carrier networks was delayed in favour of developing them as dedicated broadcasting distribution networks explicitly used to tilt the media ecology in favour of Canadian TV (Babe, 1990).

As a rule, a general-purpose network should not be taxed to support specific cultural policy aims. Instead, those goals should be dealt with directly through general taxes and politically—i.e. in the public arena—rather than through an opaque labyrinth of intra- and inter-corporate cross-subsidies along lines that developed in the 1960s and 1970s when cable television became the foundation of Canadian broadcasting and culture policy. Similar mistakes must be avoided today in relation to broadband internet access and mobile wireless networks because they already support a far wider and still expanding diversity of uses, users, services and apps than cable ever did.

Subordinating telecoms operators and ISPs to cultural policy goals would also embed conflicts of interest into the heart of media and cultural policy given the unusually high levels of vertical integration in the communications market. The Government’s pledge in the Creative Canada Policy Framework to increase the amount of funds it directly gives to the CMF to help offset the lost contributions from “cord-cutting” is a step in the right direction.[4] In a similar spirit, whatever funds are allocated to media and cultural policy should go directly to the media workers who make journalism, television, film or video games rather than to distributors with the hope that such funds will trickle down to others.

What we think of as culture policy often tends to be institutional and professionally-oriented. It is also often elitist and rooted in conservative notions of merit. A broader view, however, also sees “connectivity” policy as a form of “culture” policy because it encourages “mass self-expression” and social interaction (see Cas- tells, 2009; Rainie & Wellman, 2014). The principle of common carriage (Net Neutrality) is also violated when companies’ control over internet access is leveraged to promote some kinds of messages over others.

These and a wide sweep of other critically import- ant issues are now on the table in ways they have not been for years. For one, the CRTC continues to address a wide range of telecoms, internet and television issues after having found core segments in each of these markets woefully uncompetitive and unresponsive to people’s needs and desires.[5] Beyond this, questions about whether there should be an “ISP tax” or a specific “Netflix tax” earmarked for the production of Canadian content remain unanswered. Beyond such specific taxes and the thicket of issues they raise about cultural policy in the “internet age”, others see no reason why Netflix, Google, Facebook, Apple or others like them should not pay corporate income and sales taxes like every other business—a stance that this author agrees with, but one that will likely be dealt with by the Finance Minister, not the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Finally, the fact that Google and Facebook are consolidating their control over a shrinking pool of advertising revenue is sharpening the conflict between them and the commercial media com- panies that still rely on advertising to survive. The internet companies now face more pressure than ever to bring them under tighter regulatory con- trol, for better and for worse—as we shall see. The widespread concerns with disinformation cam- paigns and the integrity of democratic elections in the US, UK, France, Germany and elsewhere have reinforced the drift, making them much more vulnerable than just two or three years ago. There is a sense of “blood in the water” as the push to bring them to heel seems to grow by the day. Un- fortunately, many familiar industry-insider groups appear to see the ongoing review of the Telecom- munications Act and Broadcasting Act in singular terms, as an opportunity to harness the evermore internet- and mobile wireless centric media and cultural landscape to regulatory methods and pol- icy prescriptions drawn from the past half-century.

At the end of the day, a good body of data is better than hyperbole and nostalgia. This report aims to constructively add to the discussion of these issues out of sense that we are currently living in a constitutive moment when choices made now or in the near future will have enduring and cumu- lative effects on what the media and communica- tions ecology will look like for much of the rest of the 21st Century.

The Network Media Economy in Canada: Growth, Stagnation, Decline or Recovery?

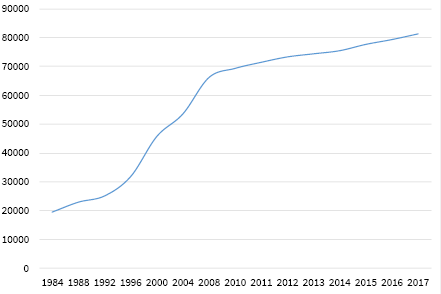

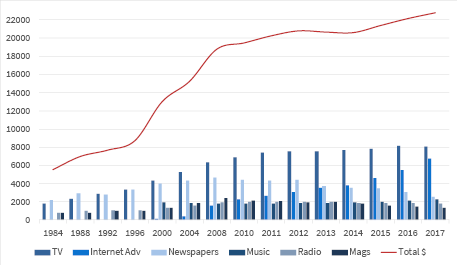

The overall network media economy continues to expand considerably. Indeed, between 1984 and last year, revenue quadrupled from $19.4 billion to $81.2 billion (current $). Figure 1 below illustrates the trends.

Figure 1: Growth of the Network Media Economy, 1984-2017 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

While the media economy in Canada is often seen as a pygmy amongst giants, especial- ly relative to the colossal size of the US media economy, the fact is that is that it ranks among the ten biggest in the world. Of the thirty countries examined in Who Owns the World’s Media, the sum total of which account for 90% of the world’s media revenues, Canada ranked 9th (Noam, 2016, pp. 1018-19).

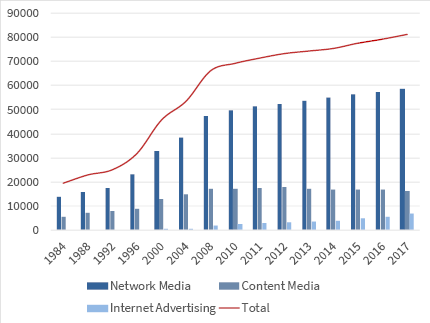

The media economy in Canada, as elsewhere, is also becoming ever more internet- and mobile-centric. “Network media” (i.e. wireline, mobile wireless, ISPs and cable, satellite and IPTV) have grown much faster than the “content media” (i.e. television, radio, news- papers, magazines, music), especially those that depend on advertising. Network media altogether accounted for nearly three-quarters of all revenue in 2017. While internet advertising has grown swiftly into a $6.8 billion industry, it represents just 8% of all reve- nue across the media economy (see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook).

Figure 2 below illustrates the divergent development trajectories for the “network media”, “content media” and “internet advertising” over the past thirty years. The most outstanding observations are, first, scale of network media is vastly larger than that of the “content media” and, second, the former has grown at a much quicker pace than the latter. Finally, while internet advertising is crucial, and growing fast, its place within the overall scheme of things is more modest than one might assume given all the attention paid to it and the sectors of the media that either depend on, or are affected by, its rapid growth, to say nothing of the two behemoths that have been its biggest beneficiaries, i.e. Google and Facebook.

Figure 3: Separate Media, Distinct Evolutionary Paths and the Network Media Economy, 1984–2017 (current $)

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

While all areas of the telecoms-internet and media industries have grown substantially over the long-run, there are unique differences among them that merit closer attention.

The rise of wholly new media sectors – e.g. mobile wireless, internet access, pay and specialty TV, internet streaming TV services, and internet advertising – has added immensely to the size of the network media economy. It has become much larger and structurally more complex as a result.

Another thing that stands out in Figure 3 is the sharp kink in the revenue lines since 2008 for all sectors on account of the impact of the global financial crisis. Indeed, the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) for the network media economy as a whole has fallen to just over two percent per year on average ever since—a third of the rate of the previous decade. In terms of inflation-adjusted dollars, the absolute size of the media economy has increased very slowly at a rate of less than one percent since 2010 amidst the uncertain economic times.

The financial crisis and economic downturn have had an impact on all media, but the severity of the impact has varied greatly. After 2008, the earlier rapid pace of growth for mobile wireless, internet access, broadcasting distribution undertakings, specialty and pay television services and even internet advertising slowed. It declined outright for wireline telecoms, direct-to-home satellite, cable television, broadcast television, news- papers and magazines. The music industry, in contrast, went into decline early in the de- cade. It bottomed out in 2012, after which it appears to have turned a corner (see Picard, Garnham, Miege, Vogel on the relationship between the fate of the media economy and the general economy).

Table 1 below gives a snapshot of which telecoms, media and internet sectors have grown, stagnated, declined or recovered in the past few years.

Table 1: Growth, Stagnation, Decline and Recovery in the NME, 2017

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

The Network Media Industries: Bandwidth and the Pay-Per Media are King, Not Content and Advertising-Supported Media

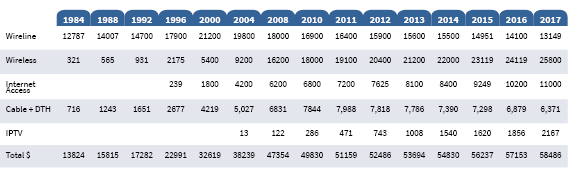

The network media industries have grown enormously, from $13.8 billion to $58.5 billion be- tween 1984 and 2017. Table 2 below shows the trends. They account for approximately 72% of all revenue, and are thus the fulcrum upon which the media economy pivots.

Table 2: Revenues for the Network media Industries, 1984-2017 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Wireline”, “Wireless”, “ISPs” and “CableSatIPTV” sheets in the Excel Workbook.

Mobile Wireless

Mobile wireless services have expanded quickly since the turn-of-the-21st century to become a cornerstone of the digital media ecology. Reve- nue grew more than five-fold during this time, from $5.4 billion to $25.8 billion last year. Wireless services also overtook plain old wireline telephone services in 2009 based on revenue, while in 2014 the number of Canadian households subscribing exclusively to mobile services for their voice calling needs exceeded those relying exclusively on land- lines for the first time (CRTC, 2015, p. 1).

The growth spurt in mobile wireless services has tracked an expanding array of devices that people use to connect to mobile wireless networks—fea- ture phones, smartphones, tablets, wifi connected laptop PCs, and so on. The scope of mobile ser- vices on offer has widened substantially as well, based on the transition from voice- and text-based networks in the early years of the century, to broadband networks that today enable a broad range of internet-based communication applica- tions. Consistent with this trend, mobile data traf- fic doubled in Canada between 2012 and 2013, and has continued to grow in the 40-60% range every year since. Cisco projects that mobile data traffic will grow five-fold between 2016 and 2021.

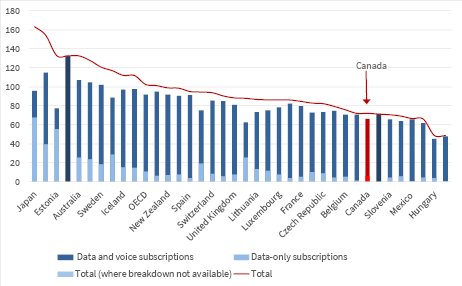

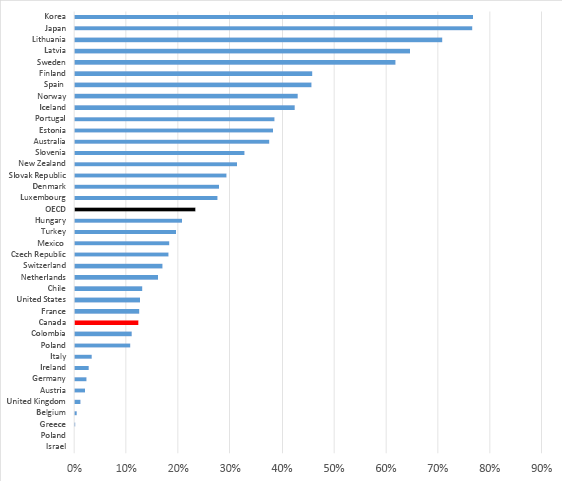

Despite this fast growth, mobile broadband (i.e. the mobile internet) adoption and usage in Can- ada continues to rank poorly against other OECD countries. Indeed, Canada ranks a lowly 30th out of 36 OECD countries in terms of adoption—a drop in rank compared to other countries over the previ- ous year. Canada also does not fare well in terms of mobile data usage, either, ranking 27th out of 36 OECD countries with an average of 1.9 GB of mo- bile data usage per subscriber per month last year. This is well below usage levels in Finland (15.5 GB), Austria (11.2GB), Denmark and Sweden (5.7 GB, respectively) and considerably less than in France (3.4GB), the US (3 GB), UK (2.5 GB) and Australia (2.1). While there are many reasons for this state of affairs, price and affordability are certainly two key considerations (OECD, 2018; FCC, 2017; Klass & Winseck, 2018). The concentrated structure of

mobile wireless markets and diagonally-integrated nature of the firms that operate in them are also key factors. Incoherent policies and inconsistent actions by the CRTC, Competition Bureau and ISED/Industry Canada also contribute greatly to this state of affairs (see Middleton, 2017 and Ben- kler, et. al. 2009).

Like other sectors, revenue growth in mobile wireless slowed post-2008. Some have argued that this is the result of a maturing market (Church and Wilkins, 2013, p. 40) but this single-minded focus is myopic.

For one, the pace set during the early uptake of new technologies cannot be sustained forever. Mobile wireless has unsurprisingly followed the classic “S-pattern” of diffusion, i.e. slow adoption at first, rapid uptake as the new technology be- comes mainstream, and a return to flatter growth thereafter as “late adopters” come on board.

However, more than just following the typical “technology diffusion curve”, the flattening of mobile wireless growth dovetails with the finan- cial crisis. In fact, revenues for the network media economy worldwide declined between 2008 and 2009. Some of the world’s biggest media econo- mies shrank in the next few years thereafter (e.g. Germany, UK, Italy and Spain), while others stalled (e.g. Japan and France) or grew only modestly (e.g. US, Canada and Korea). Mobile wireless revenues were not hit as hard as other media sectors by the collapse of the dot.com bubble in 2000 or the Anglo-European financial crisis (2007- 2008ff), but the recent let-up in the pace of wireless growth amidst such conditions is not surprising.

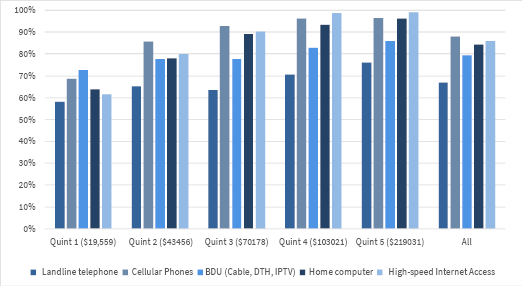

The “mature market” explanation also ignores the under-development of the mobile wireless market in Canada relative to all but a few of its OECD peers. The latest Statistics Canada data indicates that 89% of Canadian households had a mobile phone subscrip- tion at the end of 2016. That data also shows that the adoption of mobile wireless ser- vices, as well as other information and communications media, is highly unequal and stratified by income.

For households in the lowest income quintile, nearly one-in-three do not subscribe to a mobile wireless service, while just a little over one-in-seven of those on the next rung up the income ladder stand in the same position. At the opposite end of the income scale, however, mobile wireless penetration is nearly universal at 96%.

Figure 4: Household Access to Information and Communication Technologies by Income Quintile, 2016

Source: Statistics Canada (2018). Dwelling characteristics, by household income quin- tile, Canada, 2016, in Statistics Canada, 2018. Survey of Household Spending.

Rogers, Bell, Telus, and other observers who are content with this state of affairs often distract attention from these low levels of penetration by touting the supposedly large number of subscribers who have smartphones. However, fewer than three-quarters of Canadians had a smartphone at the end of 2017, whereas in a majority of OECD coun- tries this number was greater than 80% (OECD, 2018). Thus, smartphone adoption in Canada is not a triumph to be celebrated but another indicator of bigger problems that need to be redressed, i.e. low levels of mobile phone adoption, high prices, and substan- tial inequalities in terms of adoption rates.

That this is so can be seen from the fact that Canada ranks a lowly 30th out of 36 OECD countries for broadband wireless penetration as of December 2017—well below levels in the US, UK, Denmark, Australia, and many other countries. Figure 5, below, illustrates the point. Moreover, this is a position that Canada has languished in for years (Benkler, Faris, Glasser, Miyakawa, Schultze, 2010; OECD, 2011).

Figure 5: OECD Wireless Broadband Subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, by Technolo- gy, December 2017

Source: OECD Broadband Portal.

Plain Old Telephone Service, Internet Access and Internet Protocol TV (IPTV)

While mobile wireless services now occupy the centre of the media universe, the wireline telecoms infrastructure that supports plain old telephone service (POTS), internet access, cable and IPTV networks con- tinues to be a pillar in the network media economy. Combined, these services accounted for over half of all network media revenue (53%) in 2017. Mobile wireless services accounted for 44% and direct-to-home satellite services made up the rest.

On its own, however, plain old telephone service revenue has fallen to $13.2 billion (current $) last year—far off their high-water mark of $21.2 billion in 2000, but with the steep drop-off abating in recent years. Those decreases, however, have been offset by gains in internet access, IPTV and cable revenues. Telecoms and cable companies have also acquired data centre operations in recent years, although the lack of available data does not allow us to gauge the size of their revenues from these activities with any precision.

Internet access revenues have grown immensely in the past decade, similar to mobile wireless. Internet access revenues were roughly $11 billion last year, up considerably from $10.2 billion the previous year, and well over five times what they were at the turn-of-the-21st century ($1.8 billion). The adoption of wireline internet access in Canada is high relative to other OECD countries, but so too are prices, while available speeds are only mediocre, household data use comparatively low (97 GB per household per month), and data caps commonplace, whereas in most comparable countries they are rare and overage charges not as punishingly expensive (OECD, 2018; FCC, 2017; ITU, 2018; Cisco, 2017).

While mobile wireless services now occupy the centre of the media universe, the wireline telecoms infrastructure that supports plain old telephone service (POTS), inter- net access, cable and IPTV networks continues to be a pillar in the network media economy. Combined, these services accounted for over half of all network media revenue (53%) in 2017. Mobile wireless services account- ed for 44% and direct-to-home satellite services made up the rest.

On its own, however, plain old telephone service reve- nue has fallen to $13.2 billion (current $) last year—far off their high-water mark of $21.2 billion in 2000, but with the steep drop-off abating in recent years. Those decreases, however, have been offset by gains in internet access, IPTV and cable revenues. Telecoms and cable companies have also acquired data centre operations in recent years, although the lack of available data does not allow us to gauge the size of their revenues from these activities with any precision.

Internet access revenues have grown immensely in the past decade, similar to mobile wireless. Internet access revenues were roughly $11 billion last year, up consider- ably from $10.2 billion the previous year, and well over five times what they were at the turn-of-the-21st century ($1.8 billion). The adoption of wireline internet access in Canada is high relative to other OECD countries, but so too are prices, while available speeds are only mediocre, household data use comparatively low (97 GB per house- hold per month), and data caps commonplace, whereas in most comparable countries they are rare and overage charges not as punishingly expensive (OECD, 2018; FCC, 2017; ITU, 2018; Cisco, 2017).

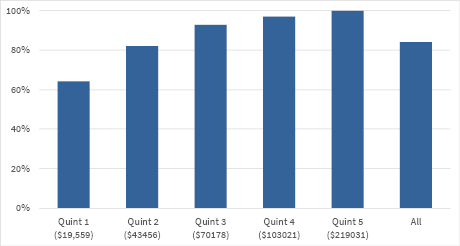

Like mobile wireless services, high-speed and broad- band internet access are far from universal. According to Statistics Canada’s most recent data (2016), 86% of households have adopted high-speed internet access service (i.e. > 1.5 Mbps). If we consider the uptake of services that meet the broadband universal service target of 50 Mbps up and 10 Mbps down adopted by the CRTC in 2016, however, the number falls to 38.6% (see CRTC, CMR 2018, Infographic 4.10). Additionally, we observe that access cuts strongly across urban vs rural and remote lines and people’s adoption of broadband is divided starkly along income lines. Figure 6 illustrates the point.

Figure 6: High-Speed Internet Access by Income Quintile, 2016

Source: Statistics Canada (2018). Dwelling characteristics, by household income quintile, Canada, 2016, in Statistics Canada, 2018. Survey of Household Spending.

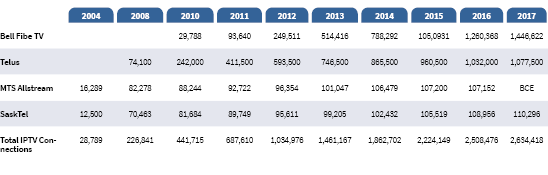

A key recent development has been the rapid growth of the telephone companies’ (e.g. Telus, Bell, SaskTel) Internet Protocol TV (IPTV) services. These incumbent telcos’ man- aged internet-based tv services now compete with traditional cable television services. The number of IPTV subscribers has more than doubled over the last five years, to 2,761,300 at the end of 2017. Table 3 below shows the trends.

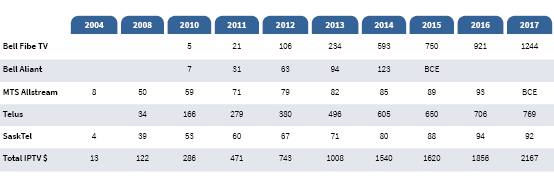

The telcos’ revenue from IPTV service has also increased sharply from $1 billion in 2013 to nearly $2.2 billion last year–again, more than double the amount five years earlier. Table 4 below shows the trends. The subscriber and revenue figures reported in Tables 3 and 4 have tended to be slightly higher than those reported by the CRTC. The dis- crepancy is probably explained by the fact that the CRTC’s data is taken from the end of August each year as opposed to the companies’ fiscal year-end, as we have done. The CRTC’s estimated “average revenue per user” (ARPU) has also been consistently lower than what the telcos cite in their own audited annual reports. Lastly, the lack of consis- tent, full disclosure by both the telcos and CRTC further obscures the exact number.

Table 3: The Growth of IPTV Subscribers in Canada, 2004-2017

Source: see the “IPTV” data sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Table 4: The Growth of IPTV Revenues in Canada, 2004-2017

Source: see the “IPTV” data sheet in the Excel Workbook.

That said, the growth of IPTV services is significant for many reasons. First, the addi- tion of IPTV as a new television distribution platform brings the telcos deeper into the cable companies’ traditional turf. By 2017, IPTV subscribers and revenue accounted for roughly a quarter of the TV distribution market—a large increase over a relatively short period of time and a change that is undoubtedly causing the cable companies to feel the increasing competitive pressures posed by the telcos’ IPTV services.

The increased competition posed by IPTV hit the western provinces earliest where Shaw has faced three companies that have been quickest to roll out IPTV services: Telus in Alberta and BC, SaskTel in Saskatchewan and, until last year before it was taken over by Bell, MTS in Manitoba. From Ontario to the Atlantic, in contrast, Bell’s roll-out of IPTV has lagged, and this deferred the competitive impact on Rogers, Quebecor, Cogeco and Eastlink until around 2013.

Cable and satellite companies are losing subscribers to the telcos’ IPTV services as a result. Altogether, they have lost nearly 3 million subscribers since 2009—the peak year for cable subscriptions in Canada. Their revenue has also dropped by 20% (~$1.6 billion) since the high point in 2011, as Table 5 illustrates.

Overall, the number of subscribers for all broad- cast distribution undertakings (BDUs as they are called in Canadian regulatory parlance) has slipped from 85.6% of households at its highpoint in 2011 to 76% last year (CRTC, Distribution Statis- tical and Financial Summaries, 2017). These loss- es—and thus the phenomenon of cord-cutting-are real, to be sure. However, they are not the calamity that some might have us believe (see the Miller Report, 2015 as an example of such claims).

Most of the cable and DTH satellite TV providers’ losses—notably, Rogers, Shaw, Videotron, Cogeco and Eastlink—have redounded to the benefit of Telus, Sasktel, MTS and Bell’s IPTV services. More- over, the loss in subscribers that has taken place has resulted only in modest revenue losses of just over four percent to the BDU sector for the last four years. This is largely because at the same time that cable subscribers were starting to cut the cord there have been steep increases in subscription prices for BDU services. Crucially, just as people have turned to the internet to access streaming

TV services directly in lieu of a cable subscription the price of internet access has jumped. Indeed, the price of subscriptions for both cable TV and internet access have risen well above increases in the consumer price index, as Figure 7 illustrates, and this continues to be the case. The sharp rise in internet access prices since 2010-2011, just as cord cutting was starting to cut into the cable opera- tors’ revenues, is especially noticeable.

The trend indicated in Figure 7, in turn, partly justified the CRTC’s efforts to promote the un- bundling of cable TV packages and pick-and-pay options in its trilogy of “Talk TV” decisions in 2015 and 2016–against the protests of industry and culture policy groups. The latter, in particular, want to retain and even extend the methods used in the past to the internet—bundling content with access to the network, and the levy on distribu- tion to subsidize content, while the former mainly want the Commission to stand aside and let the industry do as it pleases, or for the CRTC to be dis- mantled altogether and what’s left of its mandate handed to the Competition Bureau (see, for ex- ample, the reports by the C.D. Howe Institute, the Fraser Institute, the Montreal Economic Institute and the MacDonald Laurier Institute on this point).

Despite this recent reversal in direction and dispo- sition, however, the CRTC’s efforts until recently matched the realities just described and were firmly in line with similar efforts that were being taken by the FCC in the US (which have also been thrown into reverse under the Trump Administra- tion’s choice to head the FCC, Ajit Pai) as well as by regulators in Europe.

While IPTV services have taken off in many cities across the country, a few things need to be kept in mind. First, different companies have followed different strategies. For one, it was the prairie telcos, followed by Telus, that took the lead in deploying IPTV in the early- to mid-2000s. In contrast, Bell launched IPTV relatively late, first via its then affiliate Bell Aliant in 2009, before slowly rolling out the service in the high-end districts of Montreal and Toronto over the next two years—half a decade after MTS and SaskTel took such steps in the prairies. Bell’s has picked up the pace since 2012 and subscriber numbers and revenue have risen significantly for the Bell Fibe service as a result. Bell’s slow start is likely due to its desire to minimize the impact of its IPTV roll-out on its existing invest- ment in DTH satellite TV. It has turned the corner since, however, and it had nearly 1.6 million IPTV subscribers by the end of 2017. Bell has been the largest BDU in the coun- try since 2014, with a market share of just under 30% (see the “CableSatIPTV (RV)” and “IPTV” sheets in the Excel Workbook).

Table 5: Cable & Satellite Provider vs IPTV Revenues, 2004-2017 (current $, millions)

Sources: see the “IPTV” and “CableSatIPTV” data sheets in the Excel Workbook.

The telcos have also been finally ramping up their efforts to bring next generation, fiber-based internet networks closer to subscribers, mostly to neighbourhood nodes and increasingly to people’s doorsteps. If the distribution of television is key to the take-up of next generation fibre optic broadband networks, as I believe it is, IPTV is and will continue to be a key part of the demand drivers for these networks (see below).

The rate of IPTV adoption in Canada is relatively high by international standards. Just under 19% of households in Canada subscribed to IPTV services in 2017. This is similar to Spain (where uptake of IPTV reached 20% of households), China (21%) and Sweden (17%) but well above the US (9%), Japan (8%), Germany (6%), the UK (7%) and Australia (7%). However, IPTV uptake in Canada lags behind France (40%), Korea (32%) and the Netherlands (30%) (note that figures are for the end of 2016 for these other countries vs the year-over-year average for 2017 in Canada (Ofcom, p. 106).

Figure 7: The Price of Communication Services and Devices vs the Consumer Price Index, 2002-2017

Source: Statistics Canada. Table 326-0020 – Consumer Price Index, annual (2002=100)

While Canada has done well with respect to IPTV, the picture changes for fiber-to-the- doorstep (FTTP). Indeed, just 12.3% of broadband connections in Canada use FTTP— roughly half the OECD average (23.3%). At the high end of the scale, in countries such as Slovenia, Australia, Norway, Finland, Sweden, Japan and Korea, between one third to more than three-quarters of all broadband connections are fiber-based. According to the OECD, Canada ranked 27th out of 36 countries on this measure as of December 2017—a slight decline over the preceding year. Figure 8 illustrates the point.

In sum, when it comes to fibre-optic networks, the prairie telcos and Telus were ear- ly leaders, not Bell. Globally, Bell’s late turn to IPTV and FTTP in Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Provinces has also dragged Canada down in the comparative league tables. Canada continues to lag significantly behind comparable countries on this measure.

Figure 8: Percentage of Fibre Connections Out of Total Broadband Subscriptions (December 2017)

Source: OECD (2018). Broadband Portal, Table 1.10.

Broadband Policy, Politics and Public Interests: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back?

The general evolutionary pattern that we see replays a long-standing practice for new services to start out as luxuries for the rich before a combination of competitive markets, public pressures and public policies turn them into affordable necessities for people at large (see Richard John with respect to the US history, Robert Babe for Canada). Current debates over access to broadband infrastructure are the latest iteration of this old story (Winseck Reconvergence, Winseck and Pike, John, Babe, Middleton). In fact, this could be seen at the end of 2016, when the CRTC set new standards for universal and affordable broad- band internet service: minimum speeds of 50 Mbps up and 10 Mbps down to 90% of the population by 2021 (and the rest of the country a decade to a decade-and-a-half later), and with an unlimited option on offer—that is, an internet connection with no data cap, a concept that is actually the norm for most people in the developed world but rare and expensive in Canada. While policymakers have recognized that access to the internet is no longer a luxury, large strides will be needed to ensure that aspirations meet the reality on the ground, as Canada’s standing with respect to deployment and adoption of fibre-to-the- doorstep reminds us.

A similar relatively large view of the public’s interests was pursued in early 2017 under the previous CRTC chair when the regulator adopted new rules that stop the telcos and ISPs from using zero-rating to pick and choose some services, apps and content that won’t count against subscribers’ monthly data caps while everything else does. While zero-rating can be attractive to the companies as a way to differentiate their services from those of competitors, and to some consumers who see this as way of getting data for “free”, such practices are largely mar- keting gimmicks propped up by artificially low data gaps and limited choices. In places where data caps are large or non-existent, zero-rating is rarely used, whereas in countries where they are low, like Canada, it is far more common—at least until the CRTC’s ruling that effectively banned it.

Data caps are also low and extensively used where markets are highly concentrated, as mobile wire- less markets tend to be. The same is true where telephone companies own many of the most important TV and entertainment services, as is in Canada, because under circumstances where vertical integration is the norm, carriers have both the incentive and the ability to zero-rate their own services while counting everything else towards subscribers’ monthly data allowance. In other words, several structural features of broad- band and mobile wireless markets in Canada bias them toward low and restrictive data caps, with concomitant pressures from service providers to adopt “zero-rating” as an alternative to bigger data allowances, or even unlimited services as the norm versus an expensive and rare option (see, for exam- ple, Rewheel/Digital Fuel Monitor, 2018).

Ultimately, questions about zero-rating embody a philosophy of communication, one that says that when data caps are high or non-existent, people can use bandwidth to communicate, entertain, ex- press themselves, work and do with as they want— within the limits of the law, of course. When they are low, however, what people can and cannot do with “the means of communication” at their dis- posal is restricted. Seen from this angle, the issues at stake are not just about prices but whether the speech and editorial rights of people, “content creators and distributors”, apps makers and service providers come first or whether those of the tele- phone companies and ISPs are paramount. In early 2017, the CRTC ruled in favour of the first group, and drew on the principles and history of common carriage[6] to do so (see Klass, Winseck, Nanni & McKelvey, 2016).

Both rulings—the new basic service standard and the zero-rating decisions—staked out a fairly ambi- tious view of what Canadians need and deserve in “the digital media age”. On the one hand, it in- cludes affordable access to high quality communi- cation services and gives priority to the speech and expressive rights of people, content creators, apps developers and service providers over the those who own and control the networks. Consequently, people don’t have to accept only what the market gives them because communication needs have been recast in a more expansive way in the light of conditions in the 21st Century.

The telephone companies do not like this run-of- events one bit and have wasted no effort fighting to change it over the course of the last year. Thus far, however, their main success appears to have been only to slow down the pace of change and to turn back the clock with respect to the CRTC’s general disposition. The upcoming reviews of the Telecommunications Act and Broadcasting Act, and the swapping out of the public interest friendly J.P. Blais for an industry insider in September 2017, however, are fraught with risk and there is already some evidence of back-peddling by the Commis- sion.

When the new Chair of the Commission was given the reins of the CRTC he was met with skepticism but also a willingness amongst critics, reformers and public interest advocates to suspend judge- ment because in the very recent past their early suspicions of appointees who seemed too close to industry—i.e. Tom Wheeler’s position at the helm of the FCC in the US from 2013 to 2017—or too close to the government—i.e. Daniel Therrien, a former national security specialist in the Harper Government, as the head of the Office of the Priva- cy Commissioner a year later—ended up pursuing courses of actions that confounded early expec- tations, and with impressive results. That well of goodwill, however, is beginning to run dry in light of, for example:

- the new Chair’s seeming deference to industry insiders,

- the call to “harness” the internet to a model of cultural policy created over a half-century ago and maintained since (CRTC, 2018),

- similar calls by the Chair for an ISP-levy (Scott, 2018),

- the constrained basis for the Commission’s rejection of an industry proposed website blocking scheme designed to combat piracy (CRTC, 2018, TD 2018-384),

- and a seeming reluctance by the Chair to gird the CRTC’s collective spine to face the reali- ties of persistently high levels of concentra- tion and sky-high levels of vertical integration in key communications and media sectors that have not served citizens, consumers, creators or the public sphere

It may still be too early to render a final judg- ment on the current approach to policy and reg- ulation at the CRTC. However, numerous warning signs have been sounded that should not be ignored.

The Content Media Industries

Content Media and the Shrinking/Stagnating Advertising Economy

The remainder of this report looks at the content media industries: broadcast TV, pay and specialty TV, internet streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime, Crave, Illico, radio, newspapers, magazines, internet advertising and music. The analysis highlights four key themes.

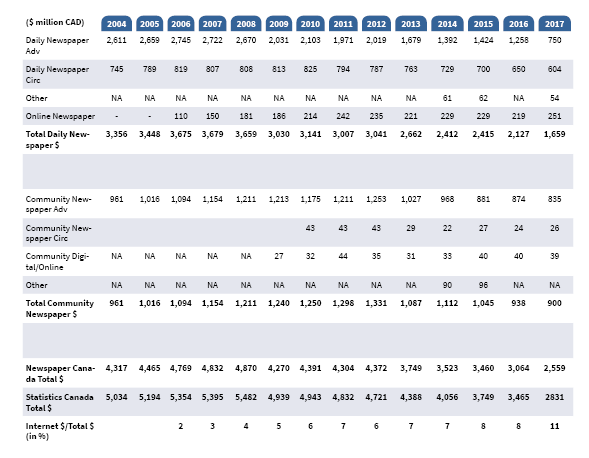

First, these sectors have grown consid- erably over the thirty-plus years covered by our project. However, most content media sectors have hardly grown at all since the financial crisis of 2008. Second, advertising is still the most significant source of revenue for the content media sectors, but the pay-per model based on subscriber fees has grown significantly over time. Third, total advertising rev- enue across all media has drifted up- wards very slowly over the past decade in current dollar terms, but it is actually declining in inflation-adjusted real dollar terms, on a per capita basis, relative to the size of the media economy, and compared to the economy as a whole.

This is a major and typically overlooked reality of the media economy. It mer- its a great deal of attention. Lastly, the advertising revenue that does remain has shifted rapidly to the internet and is being consolidated under the control of just two internet behemoths: Google and Facebook.

In 1984, nominal revenue for the content industries was $5.6 billion; in 2017, it was four times that amount, or $22.2 billion. In inflation-adjusted dollars, revenue nearly dou- bled from $11.4 billion to $21.3 billion. Growth was steady throughout this period until the Great Financial Crisis of 2008, except for several years in the early 1990s recession.

Since 2008, however, revenue for most content media sectors has fallen. As a basic rule- of-thumb, the more a medium relies on advertising the steeper the drop-off in revenue. In contrast, pay and streaming television services and the music industries have grown significantly during this period. The latter in particular appears to have entered a recov- ery phase in the past five years, after being in what many saw as a death spin in the first decade of the 21st Century at the hands of the internet and rampant piracy. Figure 9 de- picts the growth of the content media sectors covered in this report and overall. These trends reflect the fact that the fate of the advertising-supported content media indus- tries tightly follows the twists and turns of the broader economy (see Picard, Garnham, Miege and Vogel). The upshot of that observation is that media that rely the most on advertising are also the ones that are hit hardest by a weak or faltering economy: e.g. broadcast TV, radio, magazines and newspapers.

Figure 9: Revenues for the Content Media Industries, 1984-2017 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

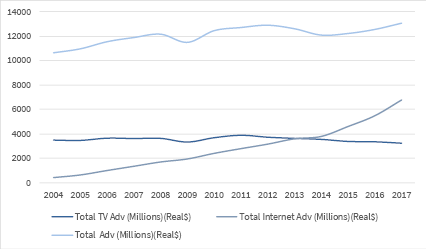

Given this, it is not surprising that the vicissitudes of advertising revenue have moved in lockstep with the state of the economy in Canada since 2008. Overall advertising spend- ing has grown from $11.5 billion in 2008 to $13.6 billion last year in current dollar terms (CAGR of 1.7%). Switch the metric to real dollars, however, and the story is one of stagna- tion, with revenue crawling up from $12.2 billion in 2008 to $13.1 billion last year (CAGR of less than 0.7%). Figure 10 depicts the point for advertising across all media and for both television and the Internet.

Figure 10: The Shrinking Advertising Economy, I—Total Advertising Revenue for Television and the Internet, 2004-2017 (Real $, millions)

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

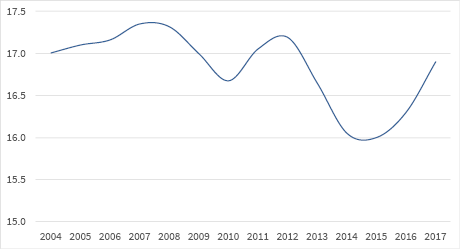

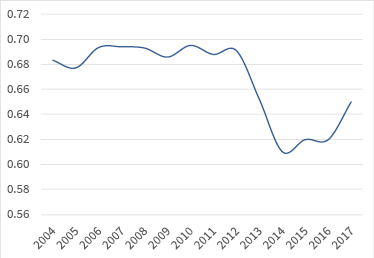

Figures 11 and 12, respectively, also illustrate the point that advertising spending is either stagnating at best or shrinking outright in real dollar terms. Figure 11 does so in relation to the size of the network media economy while Figure 12 illustrates the point in relation to annual gross domestic income.

Figure 11: Advertising Spending as a Percentage of the Entire Network Media Economy, 2004-2017

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Figure 12: Advertising Spending as a Percentage of Canadian Gross Domestic Income, 2004-2017

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Given that such realities have largely been overlooked in the existing research it is useful to sketch out a few more dimensions that help to add colour and detail to the overall picture. To do so, we can consider another telling measure, i.e. advertising revenue on a per capita basis and in real dollar terms.

On this basis, advertising spending across all media stalled between 2008 and 2012 at roughly $365 to $371 per person but fell thereafter. Last year, the downward trend appeared to turn a corner but per capita advertising spending in 2017 was still below levels five years earlier at $362. For TV alone, advertising revenue hovered around $110 per Canadian for the first eleven years of the 21st Century. Since then, however, it has fallen fast to about $86 per capita last year. Internet advertising, in contrast, has steadily risen greatly from $51 per person in 2008 three-and-a-half times that amount last year, i.e. $180.62. It bears repeating, however, that this spectacular rise in internet advertising has not offset the overall decline on either a per capita basis or in total. Figure 13 depicts these points.

The trends depicted in Figures 10 through 13 illustrate the relationship between adver- tising revenue, on the one hand, and the economy and fate of different media, on the other (see, for example, Picard, Garnham, Miege and Vogel). These figures all point to one thing: based on total ad spending across all media, relative to the size of the media economy and gross domestic income, and on a per capita basis, advertising revenue is, at best, stagnating or, worse, shrinking.

This has major implications for professional journalism, local news and original media production given the historic role of advertising in subsidizing the commercial con- tent media throughout the 20th Century. That role is now waning. It also needs to be stressed that while Google, Facebook and the internet play a role in such trends, it is unlikely that their impact alone explains the woes now afflicting advertising dependent media.

Figure 13: The Shrinking Advertising Economy, II-Ad Spending Per Capita, 2004- 2017 (Real $, millions)

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

The Rumoured Death of Television is Much Exaggerated

Broadcast TV

Advertising for broadcast television grew more or less steadily until reaching a high point of $2.4 billion in 2008. It has declined ever since. By last year, broadcast TV advertising had fallen to $1.8 million—a drop of twenty-five percent. The shift of advertising revenue to specialty cable and satellite channels such as TSN, RSN, Discovery, the Cartoon Network, etc. helped to recover some of the slack but overall advertising across the total TV land- scape has declined from a high of $3.6 billion in 2011 to $3.1 billion last year.

Cut-backs by the previous Conservative Government to the CBC of $126 million after 2012, and an additional drop of $121.1 million in payments from the Local Program Improvement Fund after 2013 until it was phased out completely by 2015, have further compounded the woes facing the CBC and broadcast TV stations (see the CBC, Annual Reports and the CRTC, CBC Aggre- gate Annual Return French and English for these years).

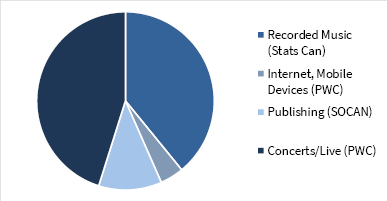

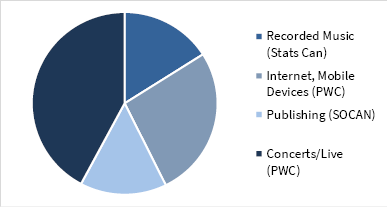

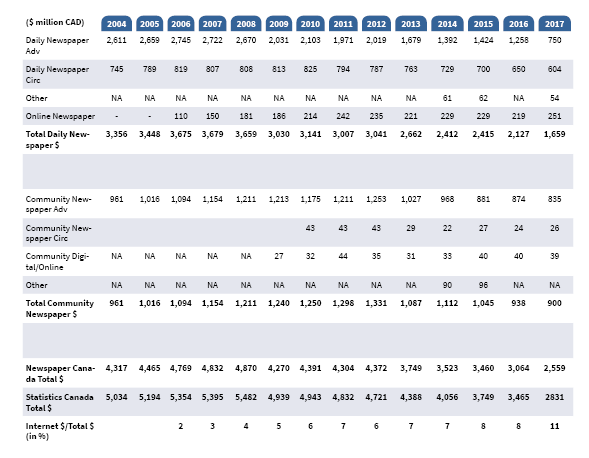

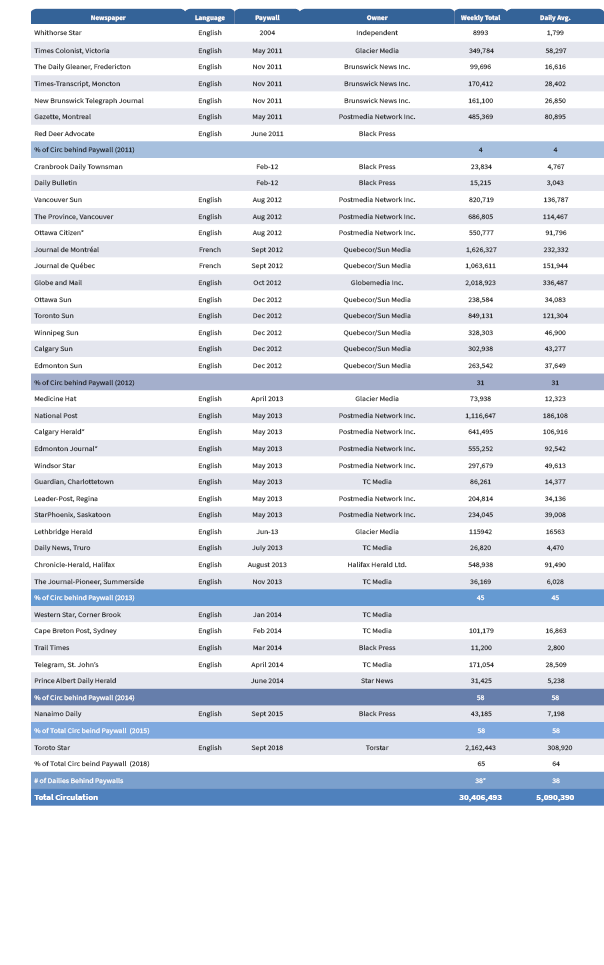

Overall broadcast TV revenues, including the CBC and its annual Parliamen- tary funding, slid from an all-time high in 2011 of $3,501.7 million to $2,728.4 million last year—a 22% decline. If we consider just the commercial broad- casters, the fall in revenue is even more pronounced, with revenue dropping 25% over the same period from $2,163 million to $1,608.3 million. As a result of these trends, eight local TV stations have closed since 2009: CHCA (Red Deer), CKNX (Midwest ON), CKX (Brandon), Sun News (Toronto), three of Rog- ers Omni affiliates in BC, Alberta and Ontario, and another station in Kenora that was closed by Shaw in 2017 (Local News Research Project, 2017).