Media and Internet Concentration in Canada, 1984–2019

Contents

Methodology: How Do We Know if Media Concentration is Intensifying or Declining?

The Historical Record and Renewed Interest in Media Concentration in the 21st Century

Communications Infrastructure Media

Internet Advertising: The case for why Google and Facebook dominate online advertising in Canada

Do Google and Facebook Dominate Advertising Across All Media?

Broadcast Television and Radio and Specialty and Pay Television Services

Beyond the Online Video Market: Digital Games, Music and App Stores

Newspapers, Magazines and Online News Sources

Digital Audiovisual Media Services (Media Content): Growth, Diversity and Consolidation

Some Concluding Observations on the Political Economy and Power of Communication and Culture Policy

This is the second of two annual reports that review current developments and long-term trends in the communications, Internet and media industries in Canada (the first report can be found here). Its main goal is to investigate whether the telecoms, Internet and media industries in this country have become more or less concentrated over time, and whether the fear of domination by a handful of global Internet giants such as Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and so forth is justified.

The report takes the position that media concentration matters, especially in an age of mobile phones, the Internet and digital media. It is also underpinned by the conviction that, at a time when some media players are struggling for their lives, research is being weaponized in the battles over the future of the media and Internet like never before, and thus the need for reliable data and analysis is heightened.

In this context, good quality evidence and independent study of the issues at stake are very hard to come by and good stories needed to withstand those who mobilize knowledge and publicity in the service of their own interests and at the expense of the many people and different publics that make up Canadian society. The CMCR Project aims to meet these needs.

To do so, our research examines roughly twenty sectors of the telecoms, Internet, and media industries over the last thirty-five years.[1] It focuses on the communications infrastructure parts of the network media economy (i.e. mobile wireless, retail Internet access, cable television) just as much as it does on the fast-evolving digital audiovisual media that are increasingly aggregated and made accessible over the Internet:

- Online video services

- Digital games

- Music download and streaming services

- Online news sources

- App stores (i.e. Google Play and the Apple Appstore)

It also examines “traditional media”, or “legacy media”, essentially the advertising-funded mass media of the 20th Century that still carries on in our own times but is increasingly facing ever more dire straits: broadcast television, radio, newspapers and magazines.

Our focus on media concentration is not to “prove” one point or another but to help create a consistent and coherent body of data and evidence to help shed light on the complicated and fast-evolving communication, Internet and media industries, or what we refer to as the “network media economy” and to inform some of the central policy, public and regulatory debates of our time.

Of course, we also study media and Internet concentration because we think it is important. This stems from the usual concerns about the relationship between markets, communication, the free press, people and democracy.

It also reflects an awareness that the more that core elements of the networked media economy are concentrated, the easier it is for the dominant players to use their control and influence of various layers and elements of “the Internet stack” that they possess to blunt the sharp edges of competition. This happens, for example, when dominant carriers raise their prices for mobile wireless and Internet services—both at the retail and wholesale levels–or when carriers control the size of subscribers’ monthly data allowances. This type of behaviour deeply influences how people—if they have a mobile phone or Internet connection at all–use these services to access entertainment, learn about the world, play, do business and communicate with others that they care about, love or work with, amongst many, many other things.

Such considerations also extend to examining how audiences access film and television content, news, music, games, and so on. An ever-widening range of media are being aggregated and delivered over the Internet by a relatively small number of global Internet giants; as we show throughout this report, concerns with concentration and the troubles associated with market power are not limited to the infrastructure side of the equation.

Market power also confers the potential for gatekeeping power, which can manifest in new and unexpected ways. The ability to regulate which content, apps and messages gain access to a platforms’ ‘technical interfaces, software development kits, online retailing and billing systems, advertisers, audiences, and so forth, are examples. These are the ‘hidden levers of power’ that determine whether Alex Jones, Donald Trump and adult content on Tumblr stay up, come down, or are limited in their visibility.

In fact, many of the world’s biggest platforms have, essentially, forged a “content moderation cartel” (Doeuk), to share the latest in AI and Machine Learning. Originally this was done for the noble purpose of suppressing child sexual abuse material, but it has since been increasingly used to harmonize, at least to a degree, these firms’ content moderation practices in order to, ostensibly, bring them in line with their social responsibilities—and to avoid stricter government regulation.

With governments around the world conducting at least eighty public inquiries into the digital platforms and potential models of Internet regulation in the last five years or so, it is clear that these have become grave concerns.[2]

The list goes on: the more powerful Internet, communication and media companies become, the greater their ability to set exploitative privacy and data protection policy norms that differ from what people actually want. The more concentrated the market and powerful the firms, the more prone policy-makers, politicians and regulators are to regulatory capture, if not explicitly then implicitly because of their dependence on the companies they regulate for the knowledge and expertise they need to effectively do so. Making available independent, reliable empirical evidence can help to counter these undesirable tendencies.

In sum, answers to the media and Internet concentration question hold out the prospect of shining a light on the complex forces and interests that are shaping the overall communications ecology.

Our initial question also holds out the lure of new knowledge and surprising discoveries. Below is a list of a few important and, in some cases, surprising findings that stand out in this report:

- Total revenue for the network media economy last year in Canada reached $91.3 billion—more than quadruple its size in 1984.

- While many have fervently believed that the Internet would be immune to high levels of concentration, only two digital media services that are aggregated and delivered over the Internet can be considered have met that expectation: online news and digital games.

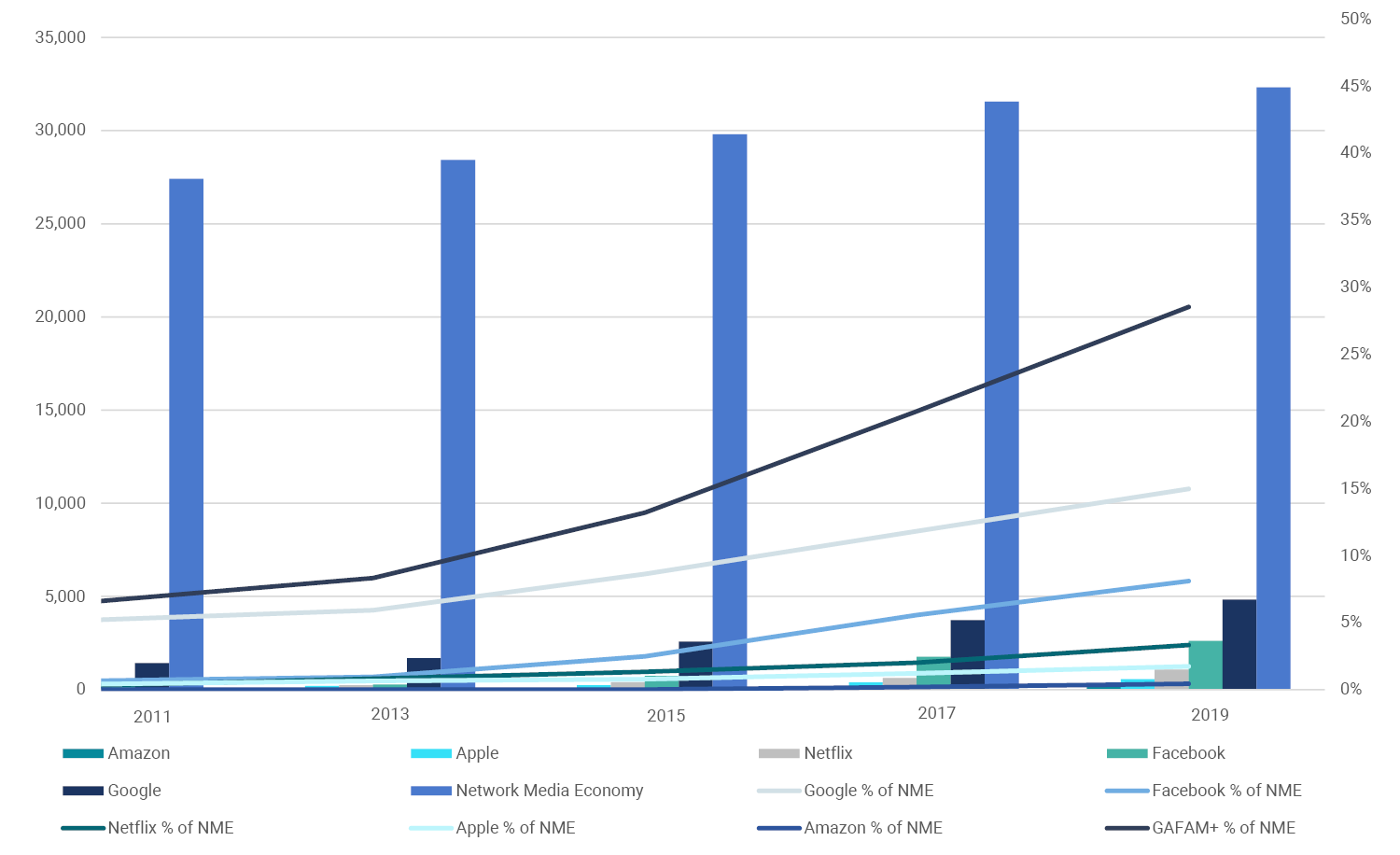

- The “big six” US-based Internet giants—Google, Facebook, Netflix, Apple, Amazon and Twitter—had combined revenue of $9.3 billion in Canada last year—close to ten percent of all revenue across the network media economy.

- With revenue of $24.9 billion and a 28% share of the network media economy last year, BCE is the biggest communications, Internet and media company in Canada—its revenue single-handedly account for close to triple that of the “big six” US Internet giants in Canada, combined.

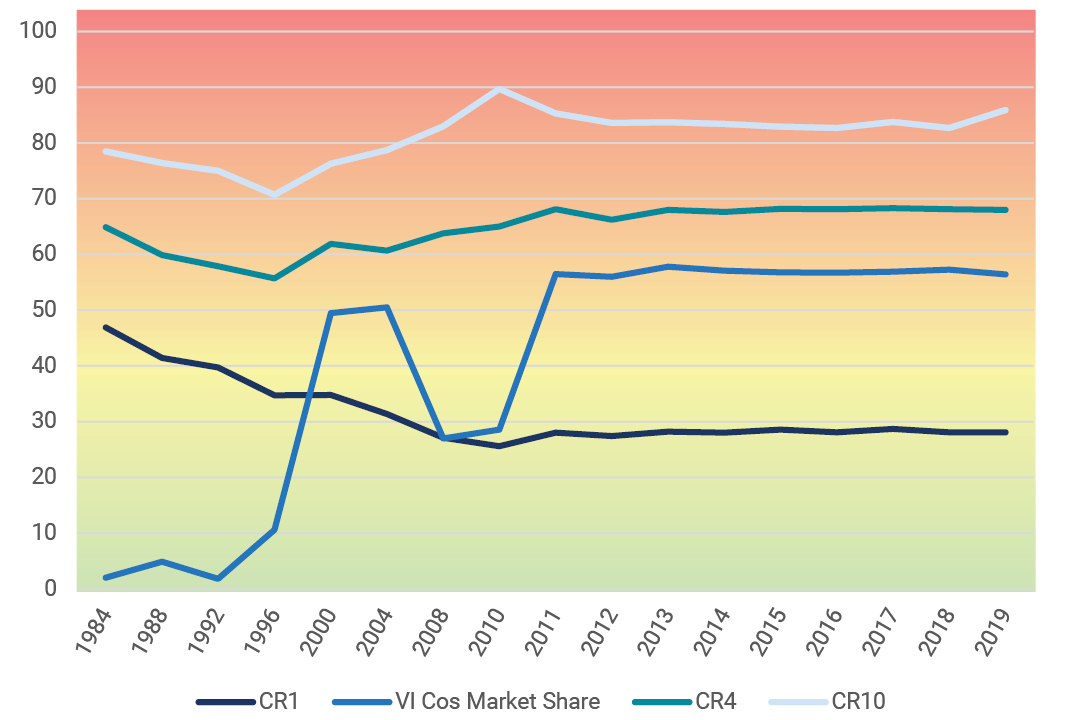

- While the top four and top ten companies’ share of the network media economy fell from 1984-1996, it then rose steadily until reaching an all-time high in 2011 where it has stayed relatively stable ever since. The “big four” then were Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Telus; they are still the big four today, with the exact same market share now as then—68%—albeit the media economy today is far larger and much more complex.

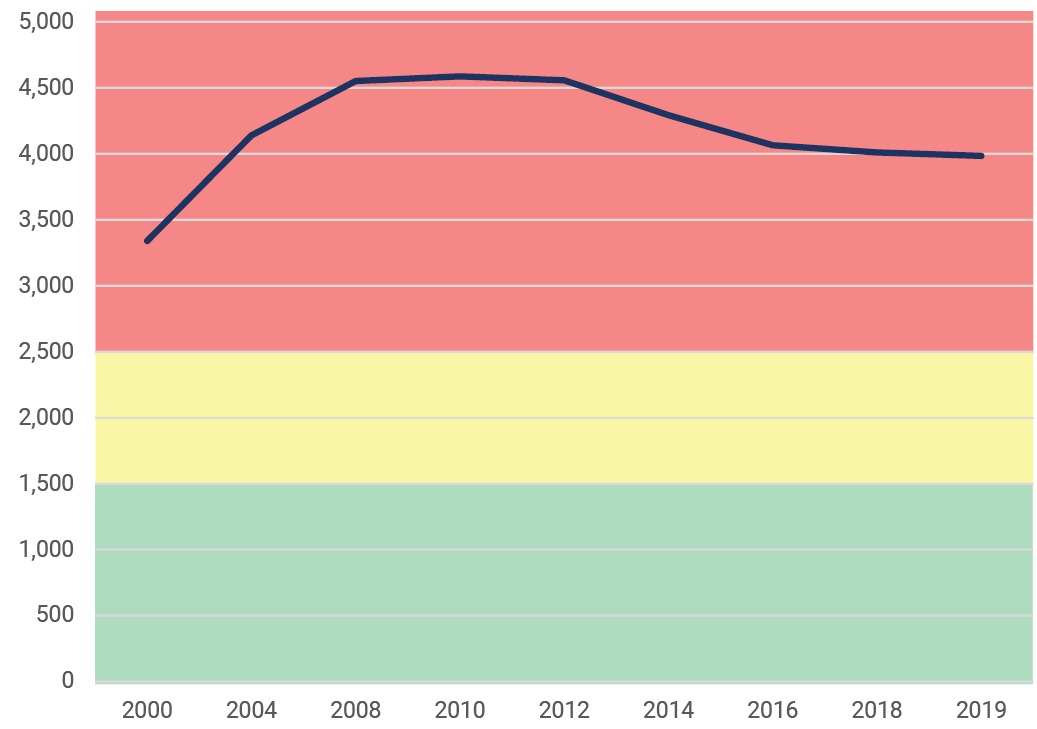

To determine whether media markets have become more or less concentrated, our research applies two commonly used economic metrics: Concentration Ratios (the CR4) and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI). Using these methods, we focus the lens on each of the media industries that we study and compare the results across media, time (history) and different countries.

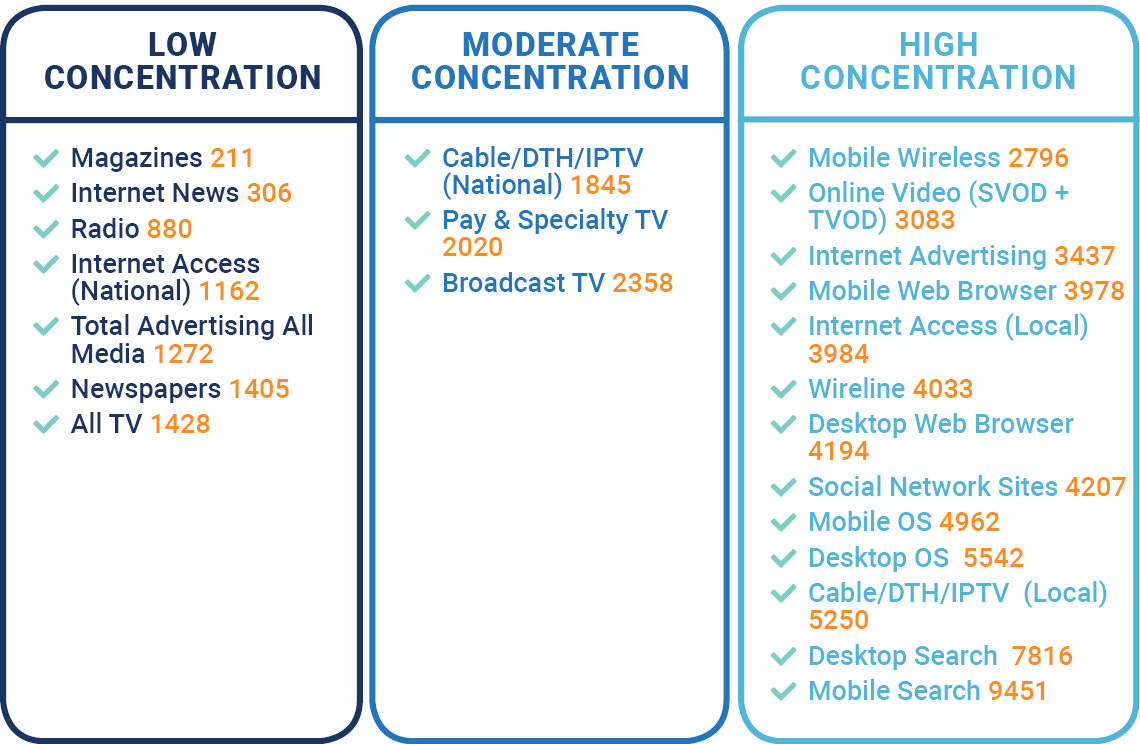

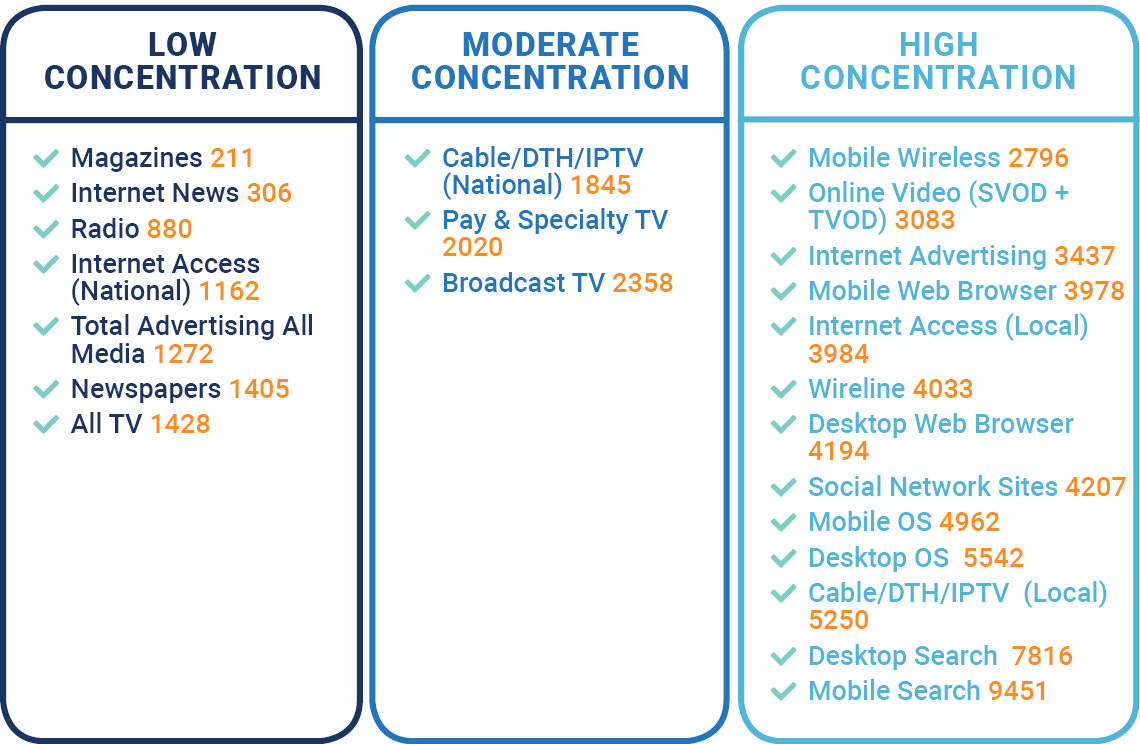

The following offers a snapshot of findings with respect to concentration levels in 2019 for each media sector covered in this report based on their HHI scores (a measure defined later in the report).

Table 1: Concentration Rankings on the basis of HHI Scores, 2019

The following passages offer high level summaries of the sector-by-sector findings from this report, followed by a summary of the report’s key findings overall.

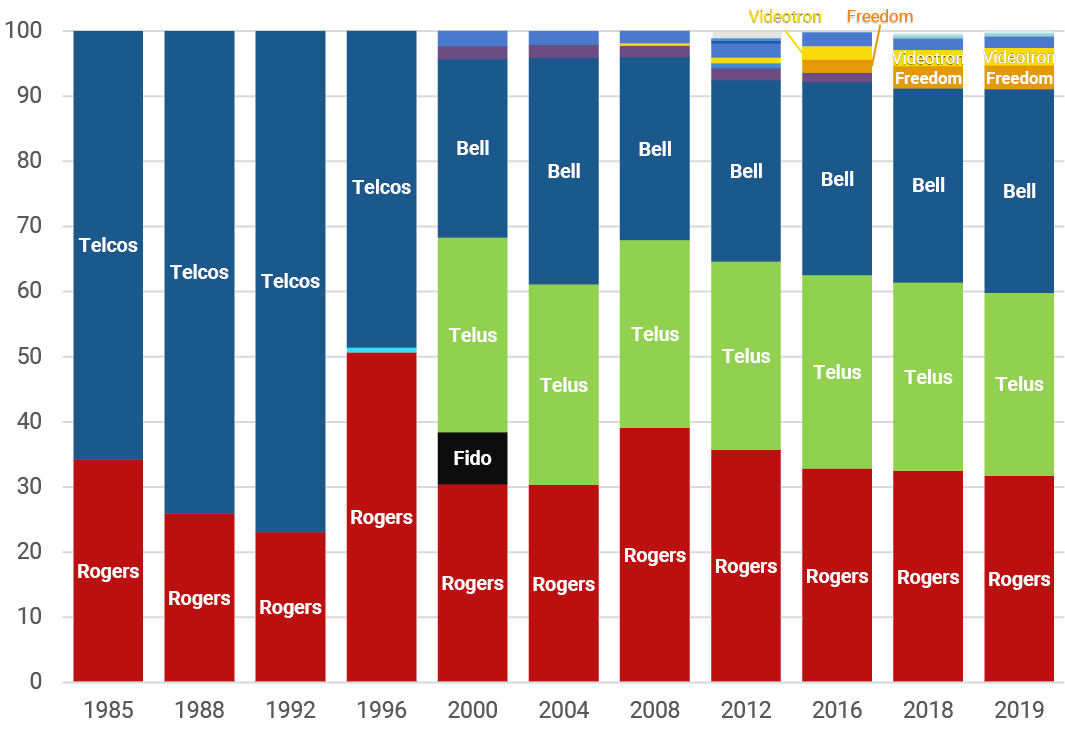

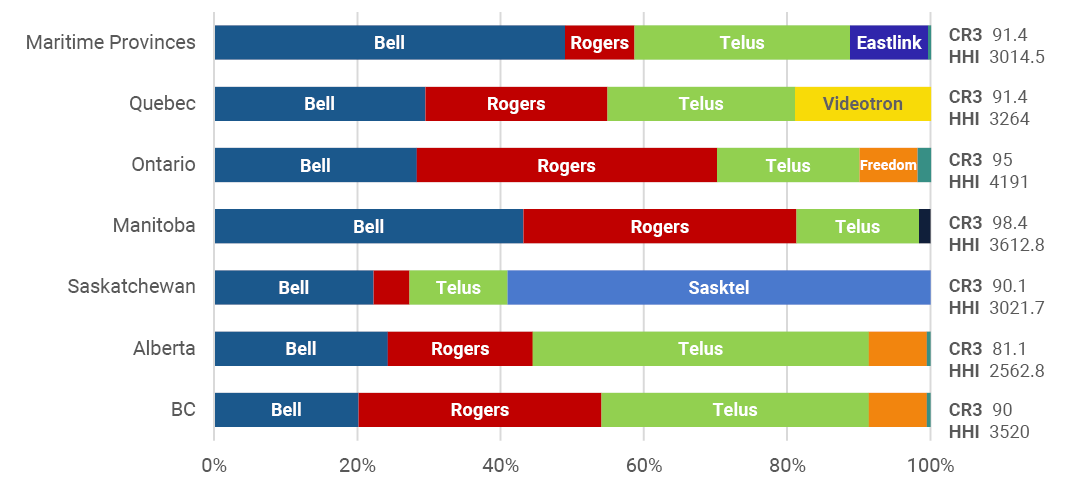

Mobile Wireless

In 2019, competition in wireless markets has improved in regions where a fourth player has emerged. For example, in Quebec, Videotron has carved out a 13% market share based on revenue (and 19% based on subscriber share) while Freedom Mobile has captured a market share of 6.4% in the areas in BC, Alberta and Ontario where it operates. That said, the big three national mobile network operators—Rogers, Bell and TELUS—have a national market share that continues to hover around 91% based on revenue—a slight decrease from 93% four years earlier—or 90% based on subscribers (CWTA, 2020).

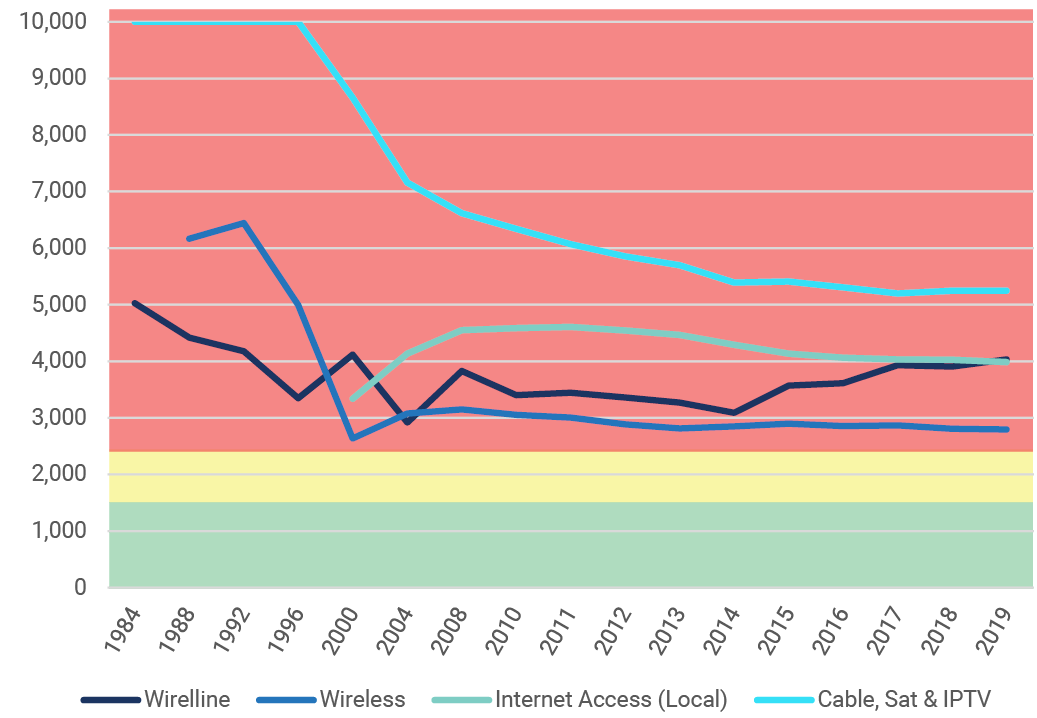

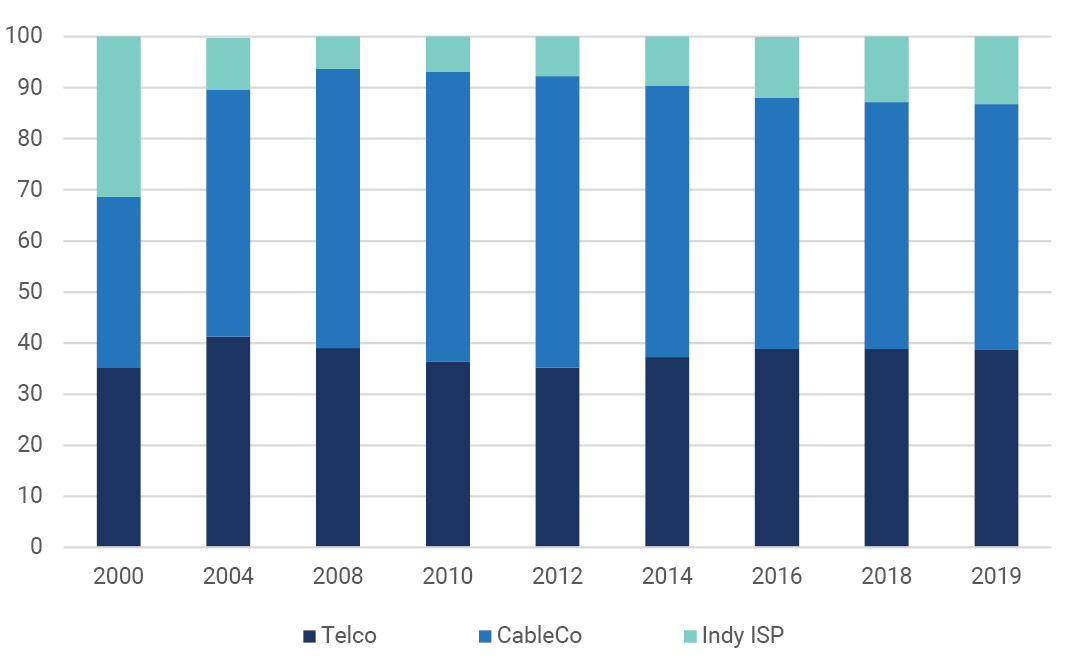

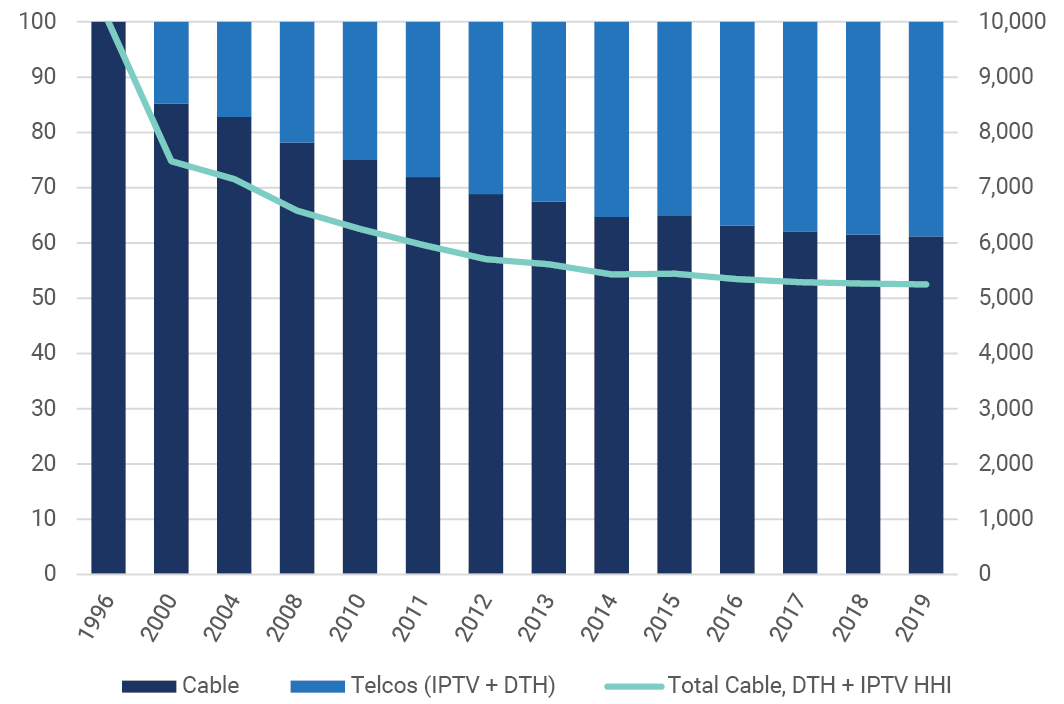

Retail Internet Access and Cable Television

Concentration levels are even higher in local retail Internet access and cable TV markets, where the legacy cable companies and telecoms operators account for 86% and nearly 100% of the market last year, respectively. In the last decade, however, the independent ISPs’ market share has doubled to 13.2% based on revenue (13.6% based on subscribers), a trend that gained traction in the wake of a series of decisions by the CRTC between 2008 and 2011 to implement a robust approach to wholesale-based competition that continues to this day. Skirmishes at the Commission, appeals to Cabinet, and in the courts over the CRTC’s decision to develop a wholesale access regime for the new generation of fibre-based Internet access infrastructure have been ongoing for five years now. These battles underscore the continued dominance of the incumbent firms and how they will fight tooth-and-nail to defend their vested interests and delay the arrival of competitors—realities that highlight the need for regulators to steel their spines if they hope to spur sustainable competition.

Wireline Telecommunications

After declining for years, concentration levels for wireline telecoms have risen in the past few years, largely due to three things: Bell’s take-over of MTS in 2017; the fact that this sector has been in decline; and the incumbent telecoms and cable companies have taken advantage of 4-play bundled communications services.

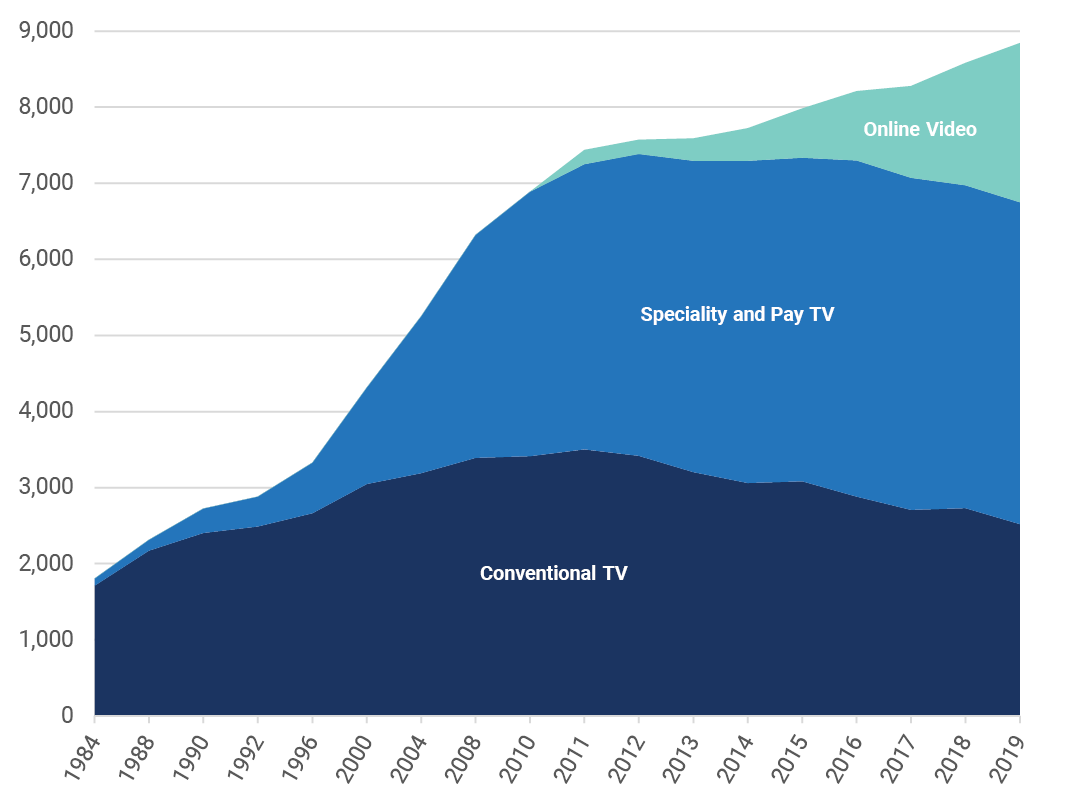

Audio Visual Media Services

After declining between 1984-2010, the level of concentration across the network media economy reversed course and rose significantly for the next few years. This shift came as result of several significant acquisitions that radically increased consolidation, cross-media ownership and vertical integration within Canada. In the last five years, the explosive growth of online video services, streaming music services, digital games app stores and online advertising—i.e. the digital AVMS sectors—has seen Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Netflix and Twitter move more deeply into Canada than ever before. Consequently, communication and media companies in Canada are facing intensifying competition with these global Internet giants, while concentration levels have begun to drift downwards, reflecting this reality. Last year, the global Internet giants accounted for more than a quarter of the $32.3 billion in revenue across all AVMS sectors.

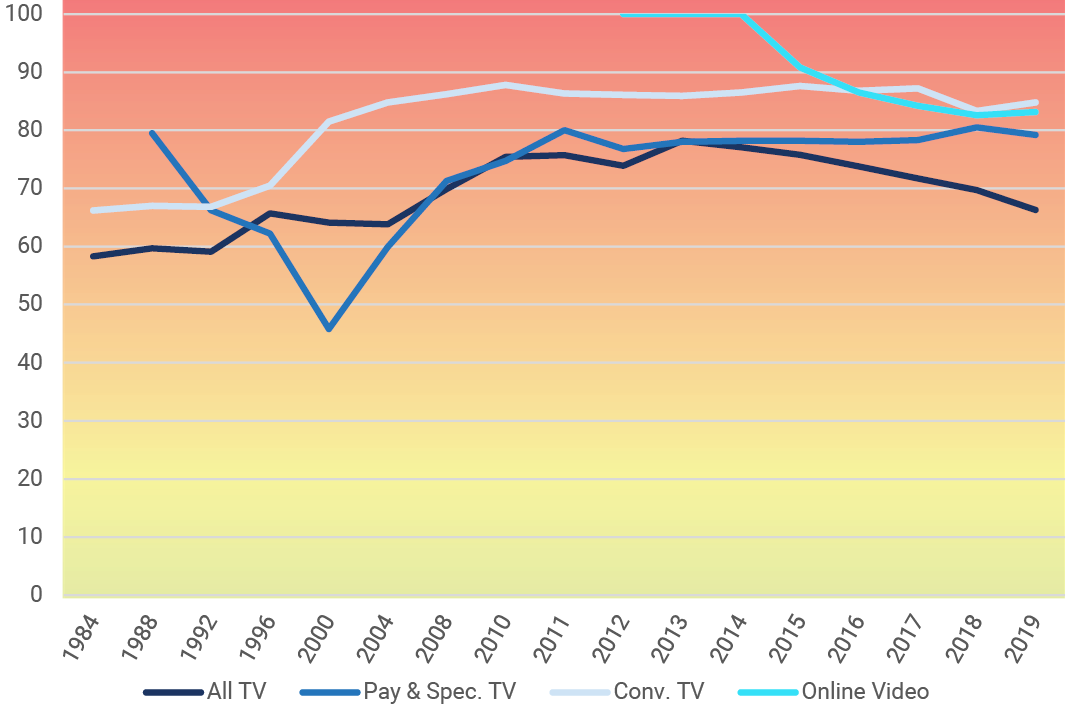

Television

With respect to television, concentration levels for broadcast TV has continuously hovered around the threshold between moderately concentrated and highly concentrated markets. When it comes to pay TV, online video services, and the overall TV universe, however, the market is expanding, becoming more diverse, and more complex. Online video services have also become more diverse over time, as Bell’s Crave, Rogers SportsNet Now, Apple+, Amazon Prime, CBC Gem and Quebecor’s illico carve out a bigger place for themselves at the expense of Netflix’s early near-monopoly on such services. On a stand-alone basis however, the online video market remains highly concentrated, with Netflix far and away the largest operator. Open the lens wider, though, and the “total TV marketplace” (i.e. the sum of the broadcast tv, pay tv and online video segments) has become more diverse in the last five years but still falls well within the highly concentrated zone by both the CR4 and HHI standards.

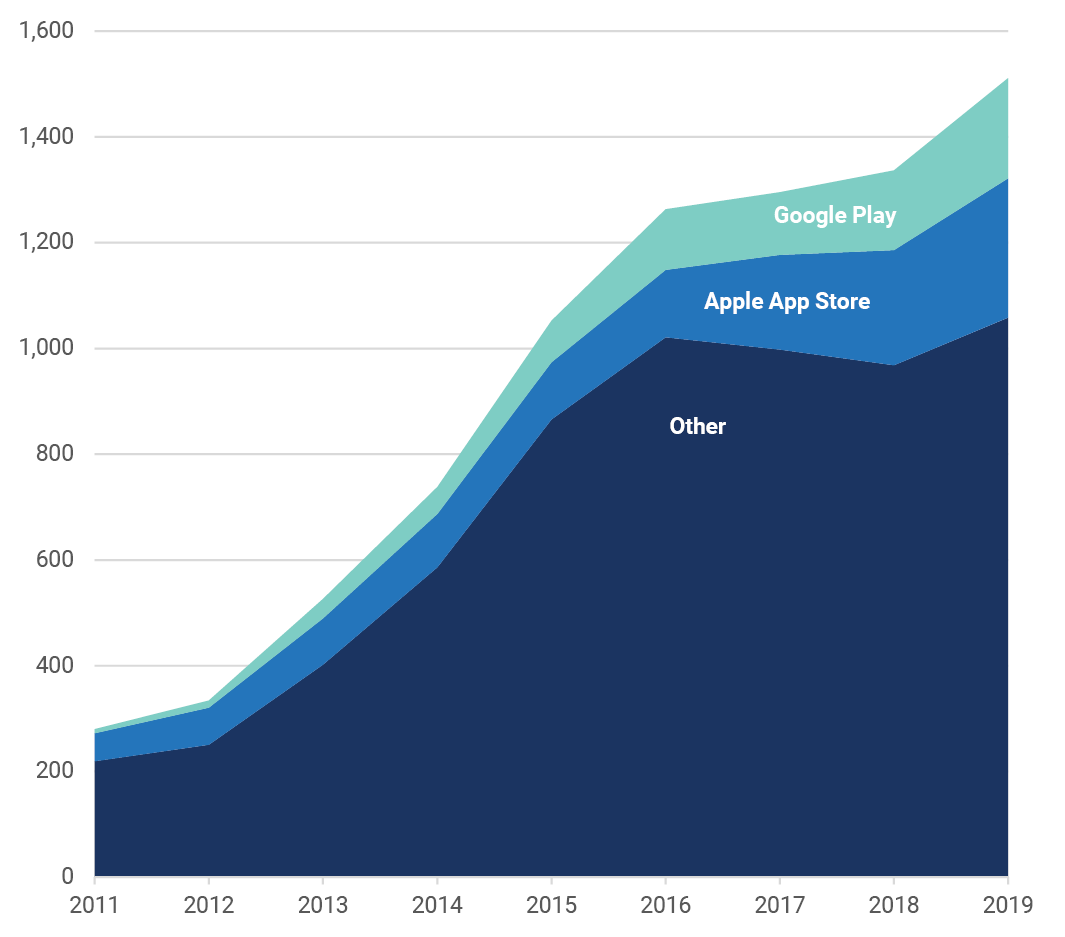

Gaming and App Stores

Obtaining consistent, high quality data for these fast-growing segments of the online digital media is difficult but the results that we present in this report are illustrative and reasonable based on the data we have been able to acquire. As this report shows, the online games, game downloads and in-game purchases sector have grown swiftly to become a $1.5 billion industry by last year. It is also characterized by a fairly diverse range of companies and business models (i.e. subscriptions to gaming platforms; subscriptions to particular games; revenues from direct-purchase game downloads and in-game purchases and advertising). Despite a crowded field, Apple’s App Store and Google Play had a combined revenue from their app stores of $979.1 million in 2019, or roughly 28% of digital games’ revenue. If we treat Apple’s iOS app store as a market in itself, three big global players stand out—i.e. Tencent, Machine Zone and Activision Blizzard—although this does not change the fact that a fairly diverse range of game publishers organized around a variety of different business models defines Apple’s app store marketplace.

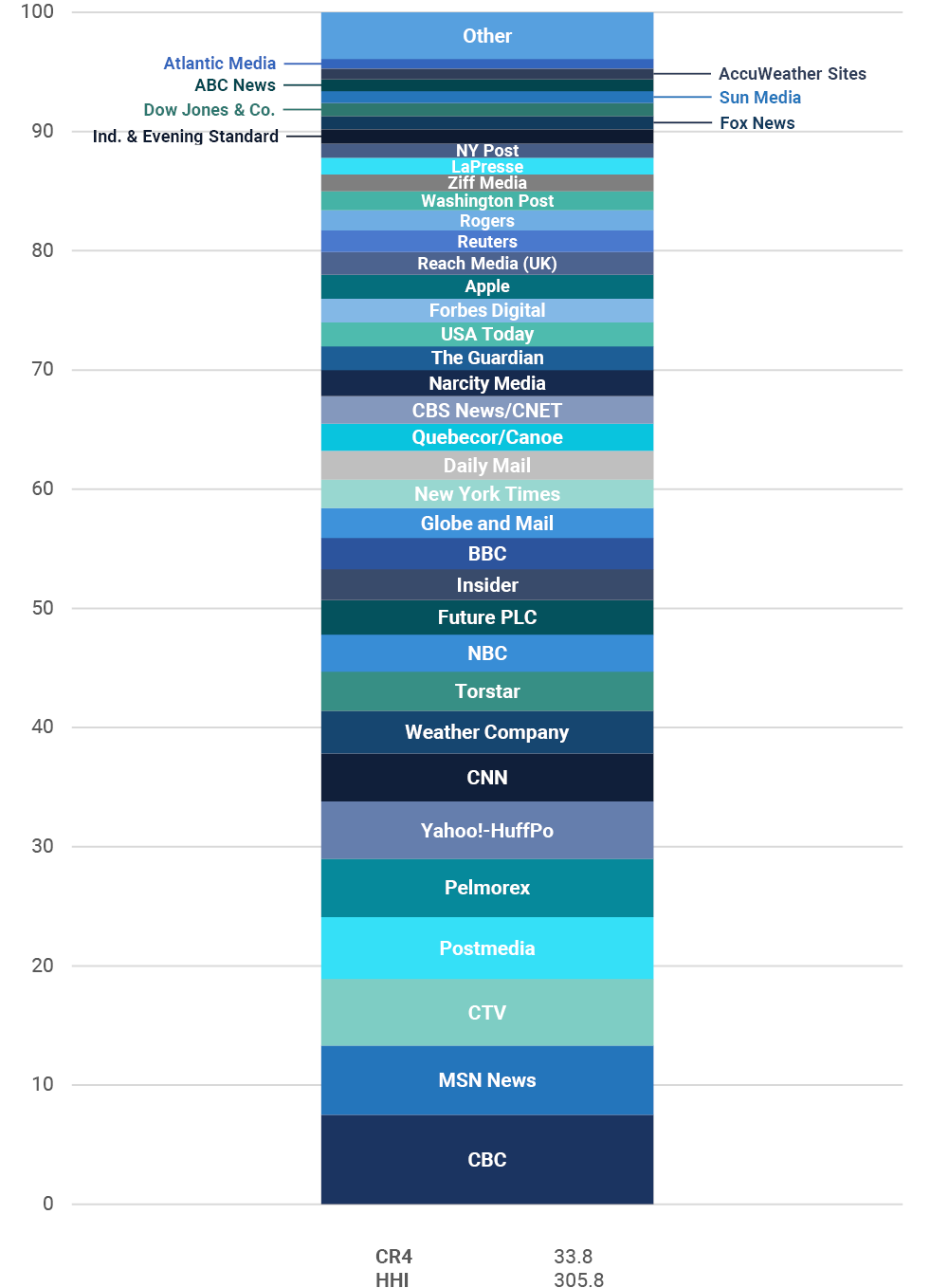

News Media: the Press and Online News Sources

The trends with respect to newspaper concentration run in two cross-cutting directions: on the one hand, newspapers are consolidating on a regional basis but, on the other hand, national concentration levels have fallen steadily over the last decade and now sit at the low end of the scale. This does not, however, reflect the development of a more diverse and healthy press, but rather responses within the industry to the reality that the press is in crisis, with revenue plunging by more than half over the last decade, as shown in the first report of this year’s series.

In terms of online news sources, Canadians continue to turn to a wide diversity of domestic and international sources, as well as well-established news organization and some newer entities. Overall, online news continues to be characterized by a great deal of diversity even though this has decreased slightly over time. That said, while relatively new sources such as the National Observer, The Tyee, AllNovaScotia, Policy Options, Canadaland, Blacklock’s Reporter, Village Media, etc. have added vibrant and credible new sources of news, information, media criticism and opinion to the media landscape, they are extremely niche in their appeal, with audiences so small that they do not even register in the rankings compiled by online audience ratings services such as Comscore.

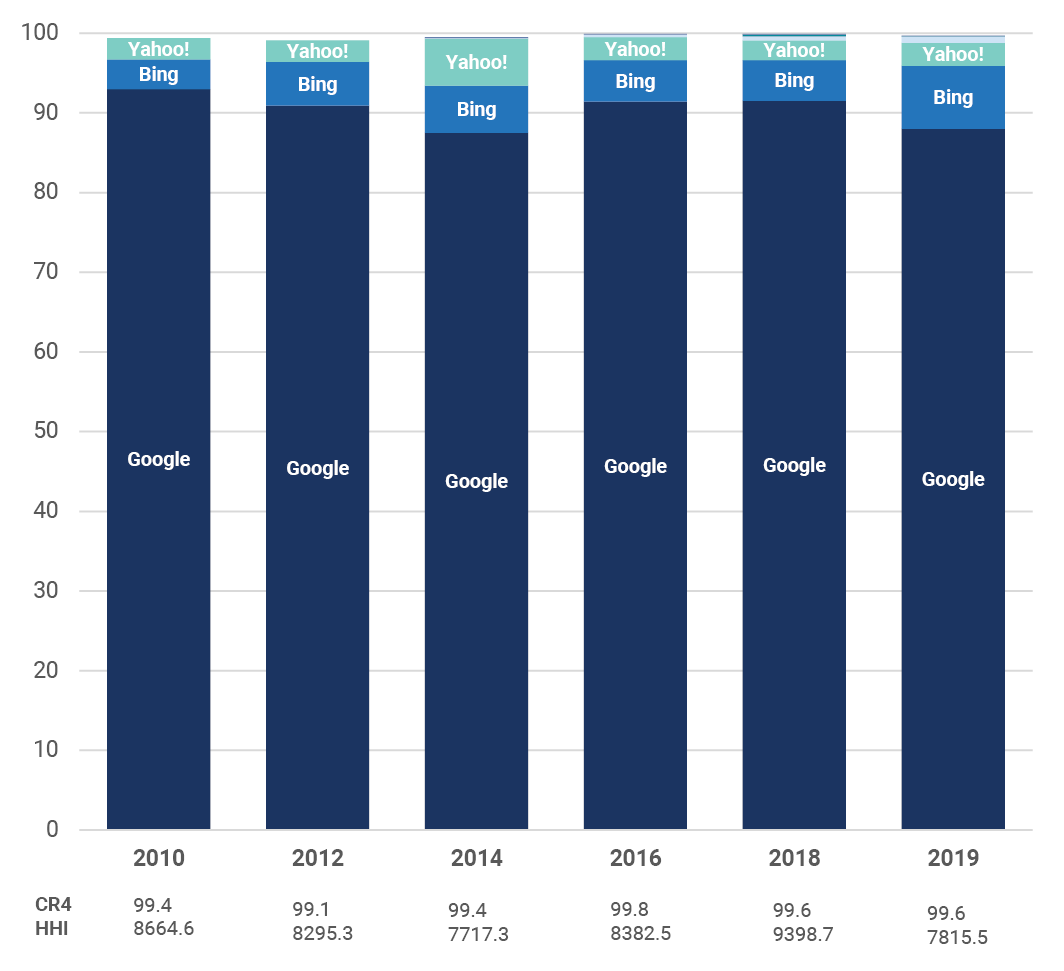

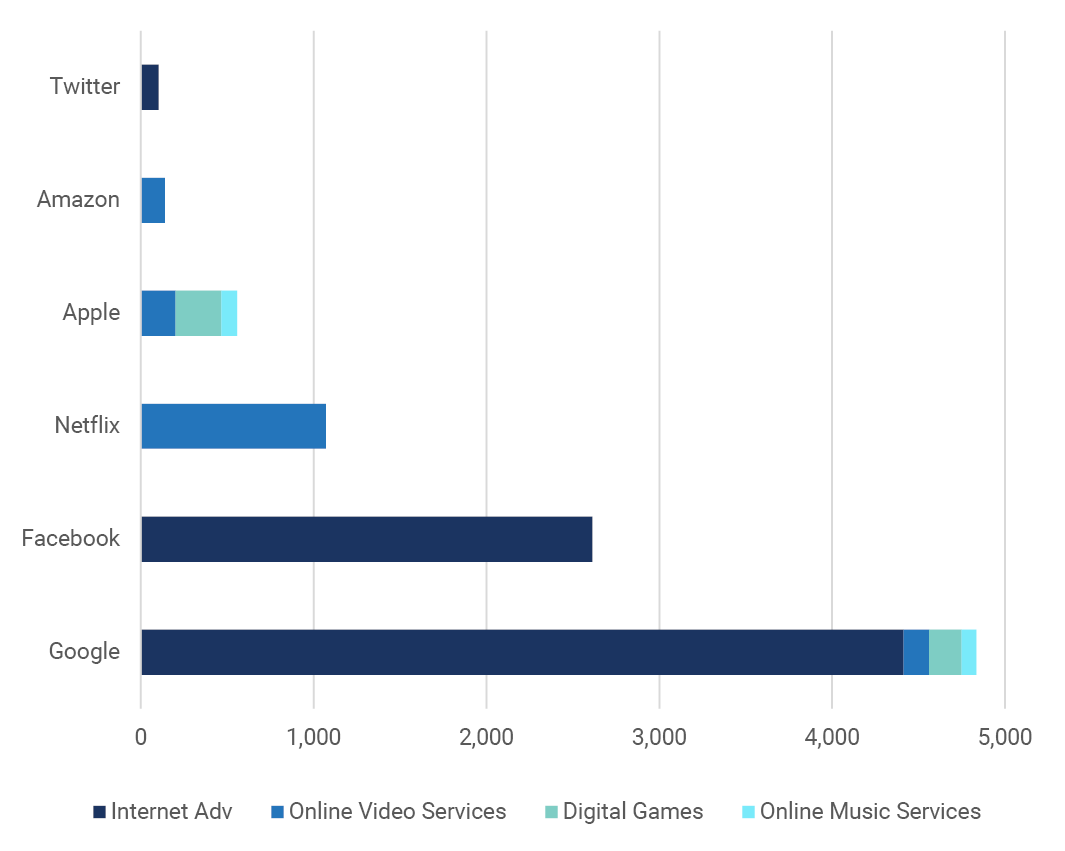

Online Advertising and Search

Strikingly, core areas of the Internet, namely online advertising, search engines, browsers and operating systems, have persistently featured sky-high levels of concentration. Thus, contrary to early enthusiasm that the Internet would be wide open, competitive and diverse, “core elements of the Internet” are susceptible to the pressures of consolidation for reasons discussed in this report.

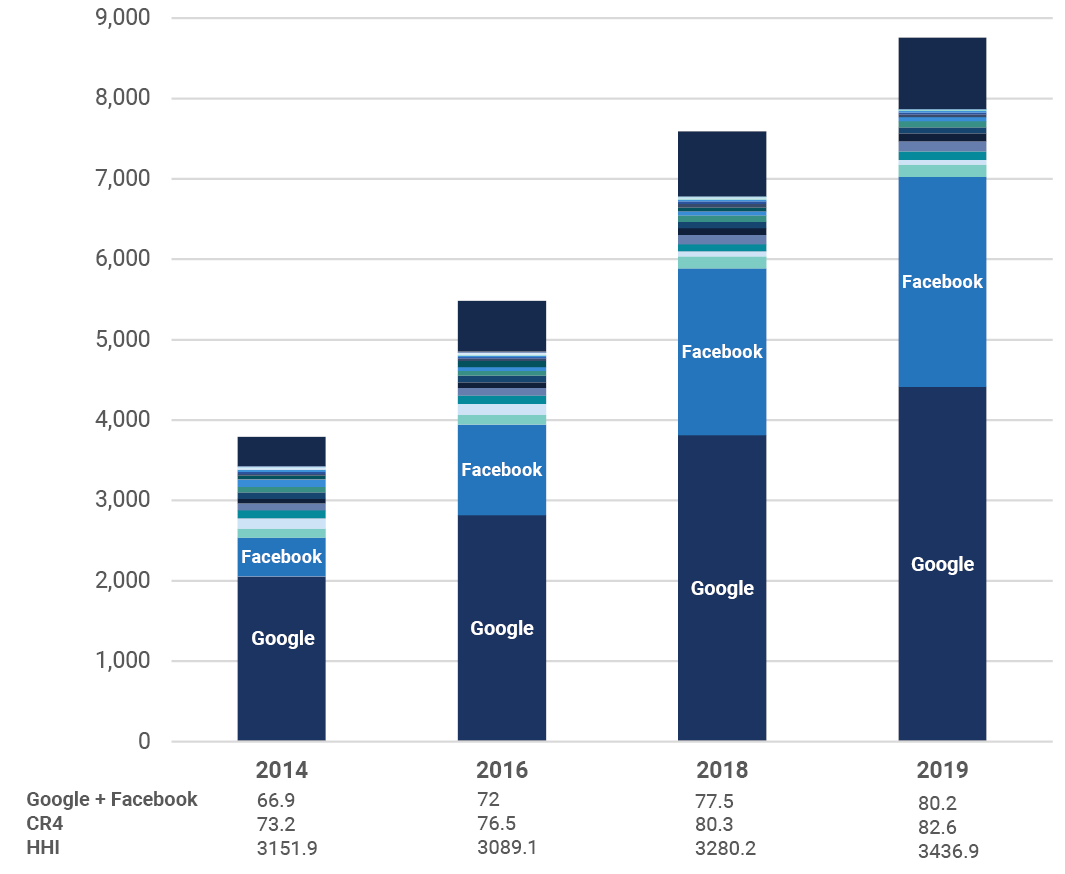

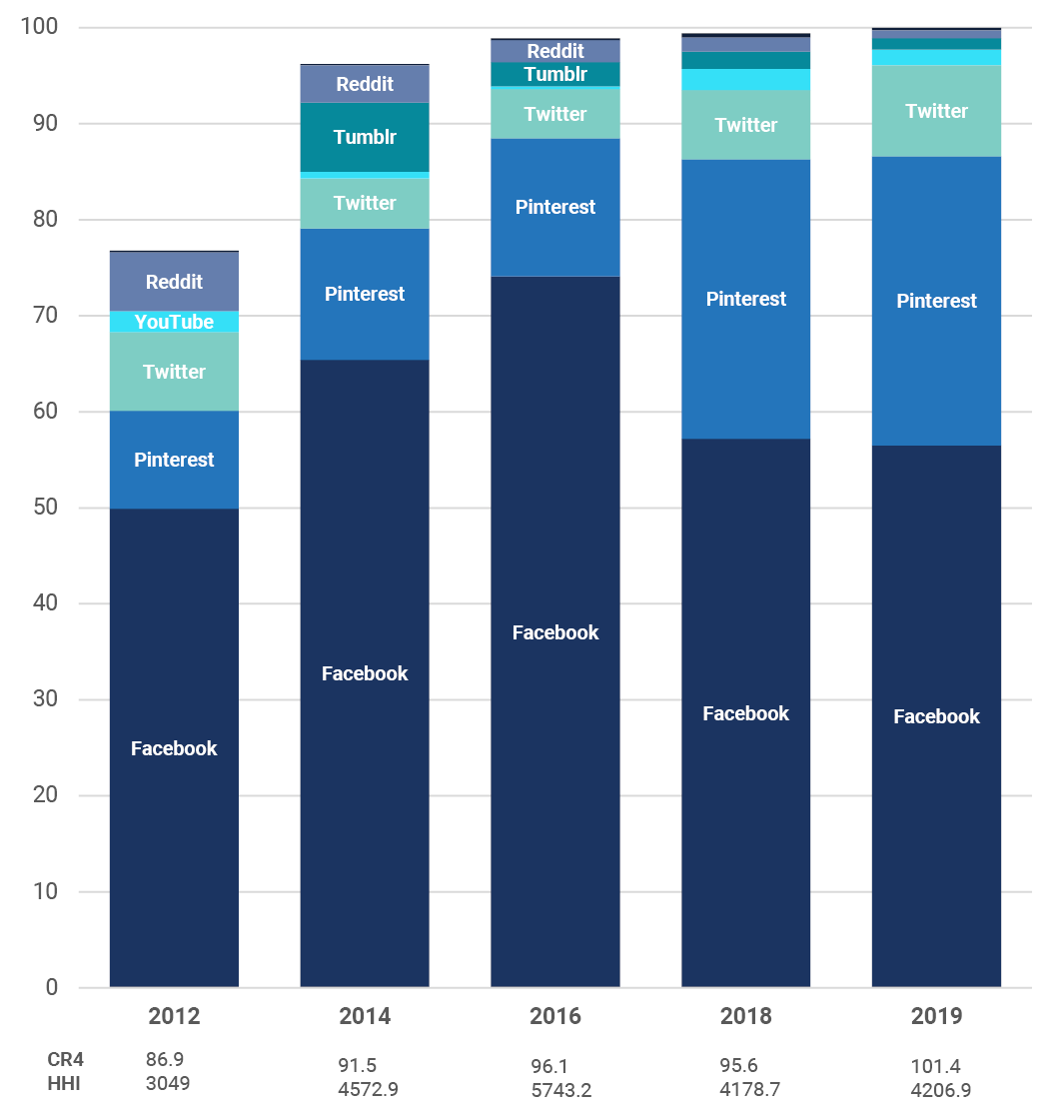

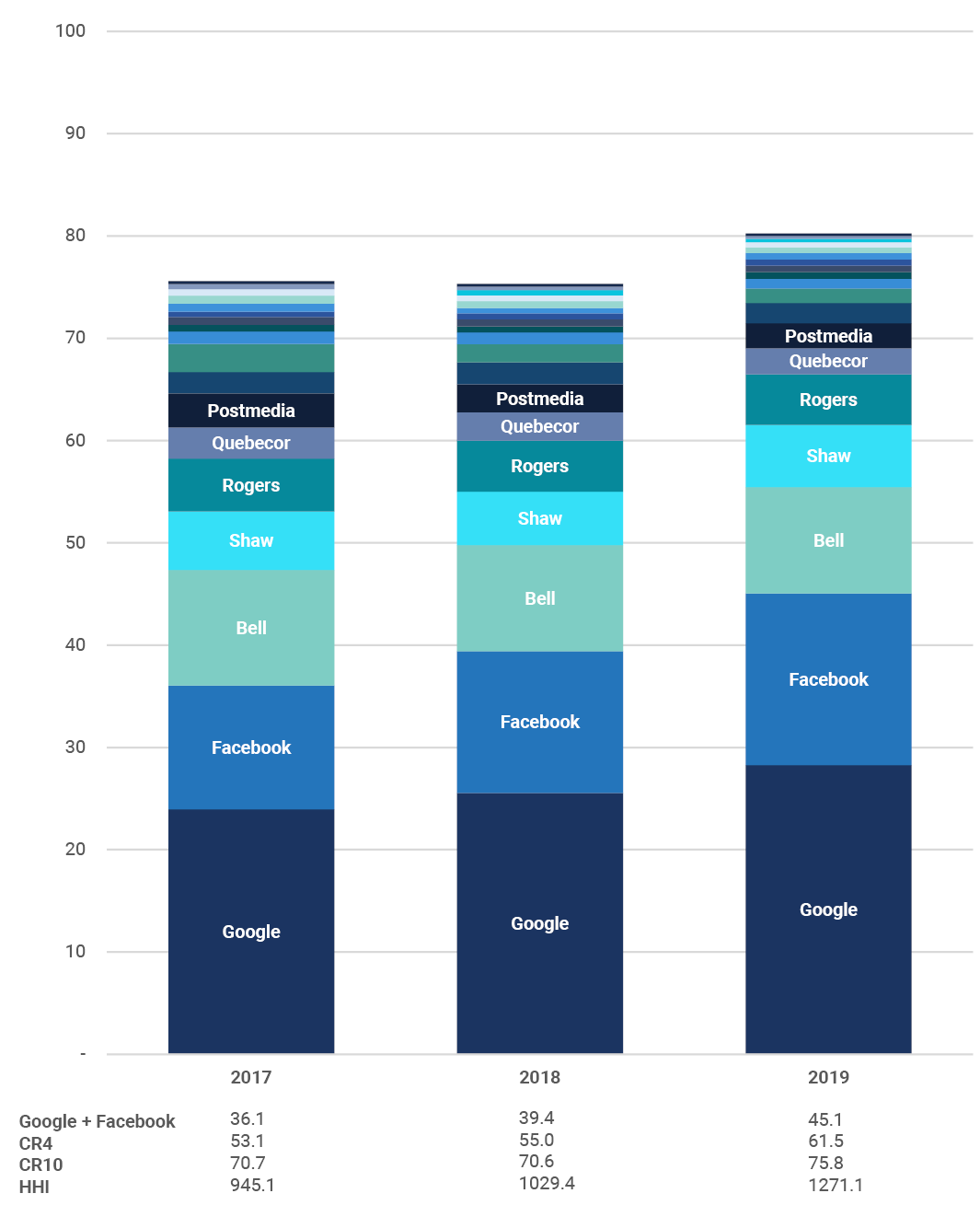

Like the first report in this series, this report focuses on Google and Facebook’s growing dominance of the $8.8 billion Internet advertising market in Canada. Last year, the digital duopolies’ combined share of the online advertising market reached 80%—up significantly from just four years ago when they accounted for two-thirds of the online advertising market.

Google’s revenue in Canada reached $4.8 billion in 2019. It now dominates online advertising (50% market share), search (92% market share), mobile search (91% market share), desktop browsers (62% market share), mobile browsers (48% market share) and app stores (43% market share). The fact that Google owns its own digital advertising exchange and controls the currency upon which advertising buyers and sellers conducts their transactions on its exchange—audience and/or personal data—underpin its dominance in online advertising.

For its part, Facebook’s user base and revenues have risen greatly within Canada as well. Last year, it had 21.5 million Canadian users across its three main services (i.e. Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp) and revenue of $2.6 billion. After a slow start, Facebook has benefitted greatly from the shift to the mobile Internet since 2012, and through its acquisitions of Instagram and WhatsApp in 2012 and 2014, respectively.

What makes Canada special?

Media and Internet concentration is generally a lot higher than people usually think. Canada is no different in this regard, even though the evidence is not all to one side. However, two things are identified in this report that do set Canada apart from other countries: first, its extremely high levels of diagonal integration between mobile wireless, wireline and cable television markets, and second, its sky-high level of vertical integration between telecommunications and television.

Diagonal integration is where mobile wireless, wireline Internet access, and cable TV—related services offered in markets that are adjacent (and sometimes overlapping) to each other–are owned by one and the same player. In most countries, there are stand-alone mobile network operators (MNOs) such as T-Mobile or Sprint in the US, 3 in the UK and Vodafone throughout Europe and many other areas of the world where it operates whereas in Canada the last stand-alone mobile operator (Wind Mobile) was acquired in 2016 by Shaw. This is important because where there are no mobile-centric operators such as Vodafone or stand-alone mobile operators such as T-Mobile, the price of mobile subscriptions and data on a per GB basis are significantly higher, while data allowances are substantially lower—all of which depress adoption levels and put undue constraints on how people use the mobile Internet connections at their disposal.

Vertical integration in the network media economy occurs when a company that owns communication networks also owns TV and other content services delivered over that network, or when a company that produced TV and film content also controls the stages either before that production (i.e. financing) or after (i.e. distribution, exhibition and intellectual property rights). Current levels of vertical integration of the first type—between mobile network and Internet access service providers (ISPs), on the one side, and television and other media content services on the other, are extremely high in Canada by historical and international standards, after basically doubling between 2007 and 2013. As a result, four vertically-integrated communications and media conglomerates have dominated the landscape ever since. In fact, Canada stands alone in the developed world on account of the fact that all of the major domestic-based commercial TV services are owned by telecoms operators.

Key Arguments, Analyses and Public Policy Proposals for a New Generation of Internet Regulation

The observations and analysis in this report fit into a broader environment where discussions about communication, Internet, media, and cultural policy are on a high boil. It is therefore helpful to dig into the evidence and these arguments to see what they have to say. A common theme in these discussions for several years now has been the tendency to denounce the global Internet giants, especially Google and Facebook, often on the grounds that they are killing the traditional media industries by stealing away their advertising, and killing journalism and imperilling democracy in the process as well.

This report argues that these arguments are simplistic, rely on a narrow base of cherry-picked evidence, and are fundamentally misleading. Instead of vilifying the “vampire squids” of Silicon Valley, this report tries to accurately gauge their scale, scope and clout within Canada—recognizing problems where they do exist, but holding firm on the conviction that their scale and scope must be accurately understood before workable solutions can be developed.

Based on a wide body of evidence, including trends visible in both this country and around the world, this report agrees that a new generation of Internet regulation is needed. In a bid to move beyond debates that centre on free market fantasies and a 1990s vision of the Internet that no longer holds, this report concludes by sketching an outline of what this new generation of Internet regulation might look like. To do so, it builds on four cornerstones: structural separation (break-ups), line of business restrictions (firewalls), public obligations, and public alternatives.[3] These principles are drawn from telecoms regulatory history, where issues of market concentration, personal data and privacy protection, public service values and limited speech regulation have been the norm for a very long time.

Rather than treating the digital platforms as if they are the 21st Century version of last century’s broadcasters and media companies, and taking broadcasting regulation and media policy as our guiding lights, the four principles offered here could serve as the basis for a robust approach to the issues before us. If incorporated into such an approach, they would give regulators the tools that they need to simultaneously deal with the “vampire squids” from Silicon Valley” as well as Bell, Rogers, Shaw, Telus and Quebecor, all of whom as the following pages will show, have a well-established track-record of fighting tooth-and-nail against any efforts to curb their influence and harness “market forces” to public interests.

An ambitious conception of a “public alternative” fit for the 21st Century “digital age” could include creating “the Great Canadian Corporation” (GC3)—a new, public service-based digital platform, communications, information and media enterprise forged out of an amalgamation of Canada Post, the CBC, the National Film Board as well as Library and Archives Canada. The mission of the Great Canadian Communication Corporation would be to provide:

Universal and affordable mobile and wireline broadband Internet service to un- and under-served communities in cities, towns, rural and remote areas across the country, building upon the tradition of universally available communication and information infrastructures.

A platform for the aggregation and delivery over the Internet of media content, information and culture made in, and of historical, social and political significance to, Canada—and effort that reflects the core hallmarks of institutions such as the CBC and NFB.

A national digital archive and library.

Headline Facts

- Bell is the biggest communications, Internet and media player in Canada by far, with $24.9 billion in revenue last year—nearly three times Google, Facebook, Netflix, Apple, Amazon, and Twitter’s revenue in Canada combined. Bell single-handedly accounted for nearly 28% of the $91.3 billion network media economy last year.

- The top five Canadian companies—Bell, Telus, Rogers, Shaw and Quebecor—accounted for 72.5% of network media economy revenue last year; in contrast, the “big six” US-based Internet giants’ combined revenue in Canada of $9.3 billion gave them a 10% market share.

- Google and Facebook are now the fifth and seventh largest entities in the network media economy in Canada, respectively. Collectively, they accounted for 80% of online advertising revenue while their share of total ad spend across all media reached 45% last year.

- Mobile wireless remains very highly concentrated with Rogers, Telus and Bell accounting for 91% of the sector’s revenue last year—a figure that has stayed stubbornly stable despite policy and regulatory measures ostensibly designed to address such conditions.

- New mobile wireless entrants Shaw (Freedom), Videotron and Eastlink’s share of the wireless market rose to 6.8% in 2019. The most competitive mobile wireless market is in Quebec, where Videotron had 13% market share by revenue and 19% based on subscribers at the end of 2019—a small increase over the year.

- Incumbent telephone and cable companies still dominated the residential Internet access market in 2019, with 86% of the $12.7 billion sector by revenue (87% based on subscribers), although independent ISPs continue to claw out marginal gains in subscribers, revenue and market share for themselves.

- The steep rise in TV concentration seen between 2010 and 2014 is beginning to be reversed on account of the rise of online video services and the spin-off of several pay TV services by Bell and Shaw (Corus) to the benefit of smaller TV operators such as DHX, Stingray, Blue Ant, Channel Zero and CHEK. The “big 5” TV operators’ took 78% of all TV revenue (including Internet streaming) last year: Bell, Shaw (Corus), Rogers, CBC & Netflix.

- Netflix had revenue of $1.1 billion in Canada last year and a 12.1% stake of all television services revenues. On a stand-alone basis, the online video market is highly concentrated, but the trend is downward over time.

- As the crisis of journalism continues to deepen, large newspaper chains such as Postmedia, Torstar and Quebecor have spun off daily and community papers while consolidating their activities on a regional basis. As a result, the top four firms’ share of revenue on a national basis has fallen from 83% in 2010 to 62% last year. Rather than being a gain for diversity, however, the decline is taking place as even leading newspaper groups struggle to survive.

- Online, Canadians get their news from a wide plurality of news sources, both old (CBC, Postmedia, CTV, Toronto Star,) and new (National Observer), as well as domestic and foreign (CNN, CBS, BBC, NBC, Guardian, New York Times).

This report seeks to answer the following deceptively simple yet profoundly important question:

Have telecom, Internet and media markets in Canada become more or less concentrated over time and how do we know one way or another?

This question is surprisingly difficult to answer because the issue is highly politicized and good data is hard to come by. As McMaster University professor Philip Savage observed a decade ago, debates about media concentration in Canada “largely occur in a vacuum, lacking evidence to ground arguments or potential policy creation either way”. Concerns with media concentration also tend to be episodic and hinge on the events of the moment. The lack of common research methods adds to the problem too. Without clearly defining ‘the media’, some researchers see them as forever becoming more concentrated.[4] Others cast the net widely to include traditional media, data-driven platforms, ICTs, mobile phones, Internet access, the Internet-of-things, and others—creating a vast ‘digital ecosystem’ where even the biggest digital media goliaths appear as tiny specks.[5]

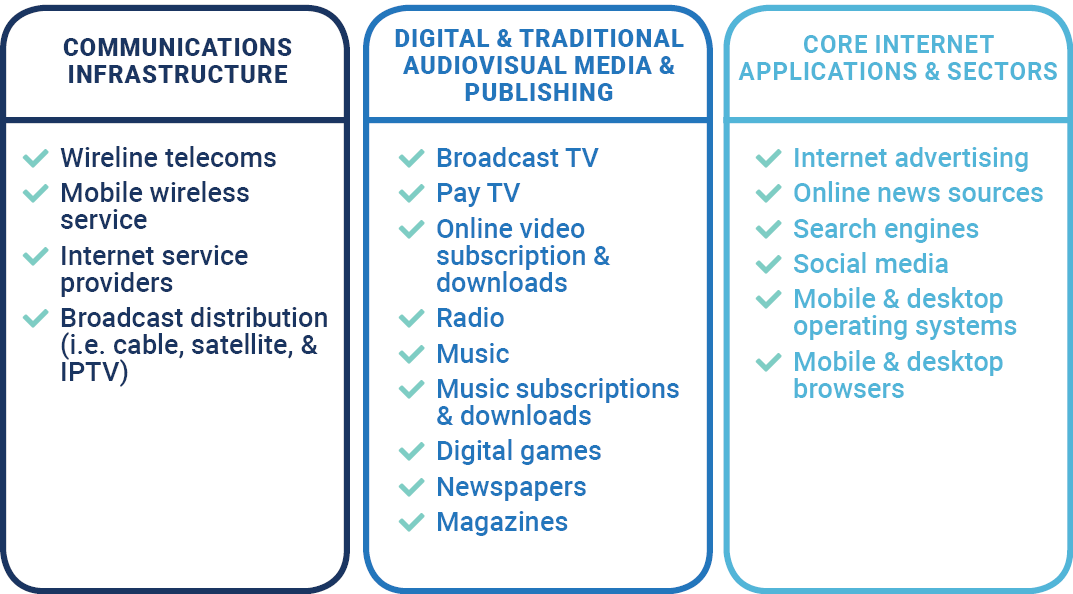

Given these challenges, it is essential to clearly delineate the scope of the terrain from the outset. This report—and the CMCR Project generally—does so by analyzing developments and trends across twenty of the largest sectors of the telecoms, Internet and media industries over a three-and-a-half decade period, as depicted in Figure 1 below. We refer to the totality of these sectors as the network media economy.

Figure 1: The Network Media Economy in Canada–What the CMCR Project Covers

Each of these media sectors is examined on its own, and then we group related, comparable industry sectors into three more general categories: the “communications infrastructure”, the digital and traditional AVMS and finally, “core Internet applications and sectors”. Ultimately, all twenty sectors are combined together to get a bird’s-eye view of the network media economy as a whole, taking care to explain how the sectors interact with one another and fit together. Two common tools are then used to assess the direction of trends one way or another within each sector individually, then for each of the three more general categories and, ultimately, across the network media economy as a whole: concentration ratios (CR) and the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI).

We call this the scaffolding approach, and its main purpose is to clearly and precisely define the media so that readers know what is included in our analysis and what is not. The objective is also to give both a detailed, micro-level analysis of individual communication and media sectors as well as a macro-level view of the whole, and to see how the former relate to one another and fit into the bigger picture. Lastly, the goal is to ensure that apples-to-apples comparisons are being made with other studies, both within Canada and internationally.

Why Media Concentration Matters

There are, broadly speaking, four schools of thought on the significance of media concentration in our current era, which we survey briefly to provide a sketch of the theoretical landscape that informs the analysis in this report.

Gales of Creative Destruction

The predominant school of thought argues that if there was ever a golden media age, we are living in it now.[6] MIT Professor Ben Compaine (2005) offers a terse one-word retort to anyone who thinks otherwise: Internet. Chris Dornan and the Public Policy Forum (PPF), the latter in its Shattered Mirror (2017) report, are emphatic that media ownership concentration is no longer a concern given that the range of information sources and how people communicate with one another have “exploded on the Internet”. If anything, this school is concerned more with the alleged fragmentation rather than concentration of media industries.

From this perspective, we are witnessing a battle of “the Stacks”, wherein vertical integration between telecoms operators and TV service providers is an integral part of dynamic competition and should not only be expected but welcomed. Seen from this angle, any attempt to shackle telecoms and media companies with ownership restrictions created in the 20th Century will put them at a disadvantage as they increasingly compete with global digital media behemoths.[7]

As proponents of this view see things, in the “digital ecosystem”, there are telecoms operators on one side of “the Stack” versus Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft (GAFAM), on the other, with their own forms of integration and operating rules. Amidst this “battle of the stacks”, many in this first school believe that focusing on “telecoms” and “media” is akin to seeing the future through the rearview mirror.

Quantifying Media Ownership and Media Bias

A second school of thought quantitatively analyzes media to see how changes in media ownership affects content, particularly in relation to the issue of media bias. However, this body of research is often driven more by a fixation on quantitative methods and mountains of data but without making explicit its underlying theoretical assumptions and a seeming belief in the naïve assumption that ‘the data speaks for itself’. Given such commitments, it is probably not surprising that even high quality research of this kind tends to find that the evidence on the issue at hand is “mixed and inconclusive”—a result that has stayed remarkably consistent for decades (here and here).[8]

Moreover, even the most judicious of such research tends to place undue concern on change in content to the detriment of investigation of a broader conception of consequences. Further, as Todd Gitlin put it in a classic essay on media effects research decades ago, perhaps “no effect” might be better seen as preserving the status quo. If so, that there is no change in media content attributable to changes in media ownership might be a problem in its own right because it signals the strength of said status quo.

Media Criticism and the Threat to Democracy

A third school of thought emerges out of the work of critics who see media, Internet, wealth, and corporate concentration as being corrosive forces in society and a threat to democracy. Robert McChesney (2014) is one of the best known voices from this point of view. He does not deny that the digital revolution is changing the world; instead, he emphasizes an often over-looked fact: just like the commercial mass media of the past 150 years, the core elements of the Internet are also prone to concentration.

Most critics also see the Internet as draining money away from the media and entertainment industries—newspaper advertising especially. McChesney, however, does not lament the loss of advertising-sponsored journalism but stresses the fact that the diversion of ad dollars away from journalism to the Internet giants exposes a fundamental truth about the news: it is a public good, and most people don’t want to pay full freight. This school argues that in recognizing this, governments can reprise the role played in the United States, Europe and Canada to varying degrees throughout history: subsidizing the news as the public good that it is.[9]

Beyond just the threat to news, increased concentration in digital markets is driving a renaissance of the anti-monopoly tradition that cuts across left-right political lines. A diverse range of concerns underpins this revival, from the use of predatory corporate strategies to cement dominance, to the seemingly unlimited harvesting and utilization of personal information. Indeed, while it would have seemed crazy just three years ago to talk about, for example, Facebook or Google destroying democracy and the need to break-up these digital behemoths, today such talk is commonplace—for better or worse.

Digital Dominance and Cross Cutting Dynamics in Media Industries

The perspective agrees with the creative destruction school that the shift to the digital, Internet-centric media of the 21st Century entails enormous changes. However, rather than seeing this as reason to put away our tools because the problems of yesterday are no longer problems today, this fourth school of thought sees the ongoing shift now taking place as having unleashed a “battle over the institutional ecology of the digital environment”,[10] with the broad contours of what is to come still up for grabs. This perspective is also informed by the idea that the history of human communication is one of recurring ‘monopolies of knowledge”[11] and oscillations between consolidation and competition. Seen from this angle, it would be hubristic—or naïve—to think that our times will be any different.[12]

From this perspective, the core elements of the networked digital media may actually be more prone to concentration than in the past because digitization magnifies economies of scale and network effects in many areas: mobile wireless, search engines, Internet access (ISPs), music and book retailing, social media, browsers, operating systems, and access devices. At the same time, however, digitization greatly reduces barriers to entry in other areas, allowing many small players to flourish. In other words, the tendencies are not all to one side. As a result, a two-tiered digital media system appears to be emerging, with a few gigantic “integrator firms” at the centre and many small niche players revolving around them. Reflecting on the results of a thirty-country study, Noam (2016) observes that concentration levels for mobile wireless and other “network media” are “astonishingly high” and that while the data for content media is mixed, the trend is an upward direction.[13]

This school also takes clashes between the “tech titans” and “telecom behemoths” as critically important examples of how different factions of business battle for access to capital investment, influence over policy, and for wealth and prestige as well as political and cultural clout. The attention paid to dynamic competition retains a more appreciative role regarding the complexity, distinctiveness and contingent nature of markets. In this sense, it is closer to the Schumpeterian views of the market fundamentalists in the first school, while also retaining a more appreciative role regarding the complexity of markets, the distinctive features of different media sectors that continue to distinguish them from one another, as well as the contingency of outcomes that are often painted as all-but-inevitable in retrospect by celebrants and critics of markets and capitalism alike (“history is written by the winners…”).

It also sees cross-cutting forces at work that vary by media, time and place. Consequently, much more attention is given to empirical evidence and the details of media companies and markets in comparison to what we usually find in critical approaches or those who think that things are just fine. In this regard, our approach is deeply informed by the Cultural Industries School that has been spear-headed by Bernard Miege and colleagues in France for several decades, but which also has important adherents in Canada, South America, Europe and other parts of the world.[14]

The “fourth school” also rejects the insinuation that the alternative to the Schumpeterian dynamic, “clash of titans” view is a static and anachronistic view of markets. Unlike the market fundamentalists, it sees these clashes as constitutive of modern capitalism and the idea that we should accept this phenomenon as inevitable and consequently beyond investigation is a fantasy. Lastly, it rejects Schumpeter and the market fundamentalists’ disdain for people’s knowledge, the publics’ interests, and democracy. In fact, the extent to which neo-Schumpeterians skirt this disdain for democracy while celebrating the alleged unalloyed benefits of “creative destruction” is astonishing given that the issues in front of us are not just about any markets, technology and policy in general but communications, a subject where issues of human rights and democracy should be and are central not peripheral.[15]

The approach taken here, in contrast, sees the market as a means to an end and markets as being constituted by rules and laws forged in the hurly burly of political processes within the context of complex societies. Those rules and laws will vary by time, place and media, moreover, but the key point here is that, in a democracy, the first rule of governments is not to shield themselves, technology and or markets from the public and people’s interests but to work toward fulfilling those interests. Nor is it, as has been the case in recent years with respect to Internet governance, for governments to increasingly delegate public regulatory functions to private actors.[16] In other words, these discussions are inseparable from abiding concerns with human well-being, the rule of law and democracy. Given this, the so-called “fourth school” strives to take an expansive and complex view of all such matters, while insisting on the need to keep a sharp eye on both the details and the broad sweep of the nascent “digital media age”.

This report endorses the idea that the level of concentration in media industries matters. The more that core elements of the networked media economy are concentrated, for example, the easier it is for dominant players to use their control and influence over the various layers and elements of “the stack” they possess to blunt the sharp edges of competition and to shape the overall communications ecology (see here, here, here, here and here). Large companies that straddle the cross-roads of society’s communications also make juicy targets for those who would enroll them in efforts to promote cultural policy objectives, curb piracy, suppress “fake news”, filter and block adult content, and to otherwise serve the machinery of law enforcement and national security (see, for example, here, here, here, here, here and here).

To put it simply, the more concentrated communication and media industries are, the greater capacity for dominant players to impose their will on the communications environment without the consent of those affected—the prerequisites for legitimacy in a democracy. Some concrete examples along these lines include the ability to:

- Levels of market concentration and the number of mobile network operators and ISPs in a market have a significant effect on the price of mobile broadband and Internet access subscriptions, the price of data, and the size of monthly data allowances, all of which deeply influence how people use their mobile phones and Internet connections to access information, entertainment and educational resources and to communicate with others.

- Set the terms that influence how audiences access news, music and an ever-widening range of media forms and, consequently, the distribution of revenue and data with news media organizations, journalists, musicians, authors and other media creators and workers (i.e. Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon).

- Set exploitative privacy and data protection policy norms governing the collection, retention and disclosure of people’s information to commercial and government third parties.[17]

- Turn market power into gate-keeping power and moral authority by regulating which content and apps gain access to their operating systems and online retail spaces.[18]

- Exert inordinate amount over communication, Internet and media policy processes and regulators, with the threat of policy and regulatory capture lingering nearby, and use their gate-keeping power to enroll subscribers, audiences and media technologies in the pursuit of cultural policy goals.[19]

- Intervene in editorial matters to influence public policy, as was the case, for example, when then Bell Media Vice President, Kevin Crull meddled in CTV’s new coverage in a bid to influence the CRTC’s review of the company’s renewed bid to acquire Astral Media in 2013, and as newspaper owners in Canada have regularly done in elections. The 2015 federal election is an excellent case in point, wherein the owners of Postmedia directed the 16 dailies in its national chain of papers to endorse Steven Harper for Prime Minister (55% of expressed editorial opinion), while other dailies in Canada representing another 16% of the endoresements in that election did the same. In other words, editorial support for the Conservative party in the Canadian press in 2015 was roughly two-and-a-half times their low 30 percent standing in the polls and final voting tally.[20]

In sum, these points highlight the fact that while good analysis must flexibly adjust to new realities, it cannot do so at the expense of neglecting long-standing concerns. It also reveals that any discussion of media concentration is ultimately a proxy for larger conversations about the shape of the mediated technological environments through which we communicate, know and express ourselves in the world, consumer choice, freedom of the press, citizens’ communication rights and democracy. Of course, such discussions must adapt to new realities, but the advent of digital media does not render them irrelevant. In fact, given the great extent to which economy and society are underpinned by information and communication infrastructures, and our lives deeply immersed in such environments, thinking long and hard about these issues may be more relevant and important than ever.[21]

Measuring media concentration begins by setting out the communication, Internet and media industries to be studied. Revenue data for each of the sectors we cover, and for each of the firms within them with over a one percent market share, is collected and analyzed.

Each media sector is analyzed on its own and then grouped into three categories, before scaffolding upwards to get a birds-eye view of the whole network media ecology:

- the “communications infrastructure media”,

- the digital and traditional AVMS and finally,

- “core Internet applications and sectors”.

Results are analyzed from 1984 to 2019, with an eye to capturing changes over time, cross-media differences and making international comparisons. Lastly, two common tools—Concentration Ratios (CR) and the Herfindhahl-Hirschman Index (HHI)—are used to depict concentration levels and trends within each sector and across the network media ecology as a whole.

The CR method adds the shares of each firm in a market and makes judgments based on widely accepted standards, with four firms (CR4) having more than 50 percent market share and 8 firms (CR8) more than 75 percent seen as indicators of media concentration.[22] The Competition Bureau, however, uses a more relaxed standard, with a CR4 of 65% or more possibly leading to a deal being reviewed to see if it “would likely . . . lessen competition substantially” (p. 19, fn 31).

The HHI method is a more fine-tuned method that captures subtler changes and differences in media markets. It squares the market share of each firm in a given market and then totals them up to arrive at a measure of concentration. If there are 100 firms, each with 1% market share, then markets are thought to be highly competitive (shown by an HHI score of 100), whereas a monopoly prevails when one firm has 100% market share (with an HHI score of 10,000). The US Department of Justice embraced a revised set of HHI guidelines in 2010 for categorizing the intensity of concentration. The new thresholds are:

HHI < 1500 Unconcentrated

HHI > 1500 but < 2,500 Moderately Concentrated

HHI > 2,500 Highly Concentrated

At first blush, these higher thresholds relative to the ones they replaced seem to dilute the earlier standards that had been set back in 1992. While this may be true, the new guidelines can also be seen as being even more sensitive to reality and tougher than the ones they supersede.

This is because they give more emphasis to the degree of change in market power when ownership changes take place. For instance, “mergers resulting in highly concentrated markets that involve an increase in the HHI of more than 200 points will be presumed to be likely to enhance market power”, observes the DOJ (emphasis added, p. 19).

Second, markets are defined more precisely based on geography and the details of the good or service at hand versus loose amalgamations of things based on superficial similarities. This is critically important because it distinguishes those who would define the communications and media universe so broadly as to put photocopiers and chip makers alongside ISPs, newspapers, books, film and TV and call the whole thing “the media”.[23] In contrast, the scaffolding method that we use analyzes each sector of the communication, Internet and media industries individually before moving to successively higher levels of generality until reaching a birds-eye perspective on the network media as a whole.

Approaching the subject from multiple vantage points like this allows us to conduct integrated, empirical analysis based on observations about the realities and dynamics that are taking place within and across all levels of the network media economy. The ability to achieve this is simply not possible (and certainly would not be credible) without simultaneously paying close attention to the specific details of different media as well as “the big picture”.

Third, the new guidelines turn a circumspect eye on claims that enhanced market power will be good for consumers and citizens because they will benefit from the increased efficiencies that result. What is good for companies is not necessarily good for the country.[24]

Lastly, the DOJ’s new guidelines are emphatic that decisions turn on “what will likely happen . . . and that certainty about anticompetitive effect is seldom possible and not required for a merger to be illegal” (p. 1). In practice this means the goal is to nip potential problems in the bud before they happen. It also means that experience, the best available evidence, contemporary and historical analogies as well as reasonable economic theories form the basis of judgment, not deference to impossible (and implacable) demands for infallible proof (p. 1).

The shift towards a potentially more active approach on concentration issues in the US and EU had passed Canadian regulators by for years, but that seemed to be changing in the early-2010s. Before that change in direction, however, the CRTC’s tepid stance on concentration issues was exemplified by its 2008 Diversity of Voices policy. The policy established static and weak standards for reviewing mergers that have no sense of trends over time or capacity to analyze the drift of events across the media.

Not surprisingly, the Diversity of Voices policy has done nothing to stop consolidation within broadcasting let alone between broadcasting and the telecoms and Internet industries, as the evidence below demonstrates. The vertical integration code applied to large BDUs in control of “must have” programming services is also a weak reed in terms of protecting smaller BDUs and programming services. The CRTC, however, began to toughen its stance toward consolidation in 2012, with several rulings during the next five years suggesting that it had rediscovered market power and the will to do something about it.

In contrast to the CRTC, the Competition Bureau at least draws selectively from the US HHI guidelines while focusing on “the relative change in concentration before and after a merger” (p. 19, fn 31). However, the Bureau’s merger enforcement guidelines include a relatively aggressive “safe harbour” provision, indicating the Commissioner is unlikely to review a merger when the merged parties’ post-merger market share is less than 35%.[25] This threshold contrasts with the 30% threshold of presumptive illegality from the Philadelphia National Bank case in the United States,[26] which is seen as a sterling example of courts being attuned to the structural realities of markets by those in the progressive antitrust community. Although the Bureau’s guidelines were published in 2011, this difference is indicative of the broader history of merger enforcement in Canada, where only a single merger has been successfully challenged in court in the 110-year run of the Bureau’s merger powers.

We will return to this discussion in the context of specific CRTC and Competition Bureau decisions below. For now, the upshot of these observations is three-fold: first, concerns about the harmful potential of market concentration and the abuse of dominant market power have been found to be factually based and significant by the CRTC, the Competition Bureau and the courts. Second, these positive steps have been important because experience teaches us that, in the face of intransigent and self-serving opposition from incumbents, only principled governments and regulators can succeed in fostering more competition in the communications and media fields.[27]

Third, however, it is not clear whether the changes undertaken in Canada embody a genuine break from the institutionalized “regulatory hesitation” that has defined so much of the policy and regulatory culture in Canada in the past (Berkman, 2010, p. 163) or a mere interruption, with regulators already reverting to course after changes in leadership. Recent rulings by the CRTC with respect to affordable mobile wireless services and the Competition Bureau’s recent report, Delivering Choice: A Study of Broadband Competition in Canada’s Broadband Industry, are two of several examples that give serious pause for concern.

There has been an abiding interest in the issue of media concentration and its impact on society in Canada and the world over since the late-19th and early-20th centuries, even if such interest ebbs and wanes over time.

In 1910, for example, early concerns with the ill effects of market concentration were registered when the Board of Railway Commissioners (BRC)—the distant ancestor of today’s CRTC—broke up a three-way alliance between the two biggest telegraph companies[28] in Canada and the US-based Associated Press news wire service. Why?

It did this based on considerations central to the principle of common carriage that have played such an important and enduring role in communications history, at least in the North American context: namely, that communications carriers should not be editors who use their control over the wires (or spectrum) to decide who gets to speak to whom on what terms.

In the face of much corporate bluster, the regulator was emphatic that while allowing the dominant telegraph companies to give away the AP news service for free to leading newspapers in major cities across the country might be a good way for the companies to attract subscribers to their vastly more lucrative telegraph business, it would effectively “put out of business every news-gathering agency that dared to enter the field of competition with them” (1910, p. 275).

In a conscious effort to use telecoms regulation (operating under the auspices of railway legislation at the time) to foster competing news agencies and newspapers, Canada’s first regulator, the BRC, forced Western Union and CP Telegraphs to unbundle the AP news wire service from their telegraph service and charge a separate price for each of its two parts: one for transmission over the wires, the other to reflect the price of the AP news service. It was a huge victory for the Winnipeg-based Western Associated Press—the appellant in that case—and other ‘new entrants’ into the newspaper business as well. It was also the decisive moment when the principle of common carriage was firmly entrenched in Canadian communications policy and regulation.[29]

In short, the BRC acted to constrain corporate behavior out of the conviction that concentration within the telegraph industry as well as a kind of virtual vertical integration between telegraphs and news services would run counter to society’s broader interest in competitive access to communications and a plurality of voices in the press.

Throughout the 20th century, similar questions arose and were dealt with as the situation demanded. One guiding rule of communications policy, however, was that of the “separations principle”, whereby telecoms carriers[30] competed to carry messages from all types of users, and for all types of purposes, but were prevented by law from directly creating, owning or controlling the messages that flowed across the transmission paths they owned and controlled.

A general concern also hung in the air in government, business, broadcasting and reformist circles that those who made communications equipment, or operated transmission networks, should not operate broadcast stations, make movies or publish newspapers, books, software, etc. This could be seen, for example, when the original equipment manufacturing consortia behind the British Broadcasting Company in the UK and the National Broadcasting Company/Radio Corporation of America in the US, respectively, were ousted from the field in the latter half of the 1920s during the remaking of these entities into the stand-alone broadcasters that they eventually became. Nor should telephone companies such as AT&T play an active role in the film industry, as was the case when, after having wired movie theatres across the US and the Hollywood production studios for sound, circa 1927, AT&T took on a larger role by financing and vetting films during the 1930s.[31]

The consolidation of broadcasting under the CBC in the 1930s brought private broadcasters into the core of the Canadian ‘broadcasting system’ from the get-go. The creation of the CBC also, however, wiped out important local, foreign and educational voices, and even a small theatrical radio club in Winnipeg who were taking live theatre from the stage to the airwaves. In each case, it was the structure and organization of the communication/media system, and who owned what and in what proportions, that decided who got to talk to whom on what terms.

The separation of transmission and carriage from message creation and control was another principle that was worked out in a myriad of different ways. Aside from high-profile efforts to keep the telegraph companies out of the news business, and telephone companies out of radio broadcasting and the movie business, and the monumental impact that such decisions had on these critically important areas of the communication and media industries for the rest of the 20th Century, most of the time such concerns with the structural make-up of the communication and media industries and markets were considered tedious, boring, and tucked away in obscurity in parliamentary papers, legislation and corporate charters.

Bell’s charter, for instance, prohibited it from entering into ‘content and information publishing services’, from radio to cable TV and ‘electronic publishing’, until the early 1980s, when more and more exceptions to the general rule were adopted. The same was true for other telcos, private and public, across the country, even though Manitoba and Saskatchewan began to lay fibre rings in a handful of provincial cities and to offer modest cable TV services in the 1970s.[32]

Media concentration issues came to a head again in the 1970s and early 1980s when three major inquiries were held: (1) the Special Senate Committee on Mass Media and its two volume report, The Uncertain Mirror; (2) the Royal Commission on Corporate Concentration (1978); and (3) the Royal Commission on Newspapers (1981). While these proceedings did not amount to much in the way of concrete reform, they left a valuable historical and public record.

During the 1980s and early-1990s, the government introduced a series of gradual policy reforms that began to chip away at the previous era of telecoms monopolies and open up the broadcasting system to a range of new commercial operators and pay television services. For example, to foster the development of, and at least some limited rivalry in, new mobile wireless telecoms services, the Department of Communication licensed two competing sets of mobile wireless operators in 1983-1984: the first was a joint venture between cable television, broadcasting and publishing giant, Rogers, and AT&T-backed Cantel Communications; the second consisted of the eleven regional telephone monopolies operating across the country at the time (e.g. Bell Canada, MTS, Sastel, Telus, the Atlantic telcos), each of which now had a license to provide wireless services in addition to their plain old telephone services and to do so in competition with Rogers/Cantel in their respective operating territories (Klass, 2015, pp. 58-61).

As a more concerted effort to promote greater telecoms competition took hold, long distance competition was introduced in 1992, while two new national competitors in mobile wireless service followed in 1995 (Clearnet and Microcell). The Chretien Liberals also encouraged the telephone and cable companies to compete in one another’s former, mutually exclusive turf in 1996, while a year later the CRTC laid out its blueprint for local telephone competition. Overall, the government used several policy tools, including interconnection, interoperability and network unbundling rules, access to spectrum, wholesale pricing regulation, and market liberalization, in its bid to promote competition in telecoms and broadcasting. In some regards, the efforts were a success, as competition gained traction and concentration rates fell across the board as a result, except in cable television distribution.

The 1980s and 1990s were also characterized by the steady growth of broadcasting as well as the relatively swift rise of pay and subscription television services. These sectors were cultivated by a combination of well-established broadcast television and radio ownership groups as well as a few relative newcomers, such as Allarcom and Netstar. These newcomers, in turn, often entered the broadcasting field from unallied businesses. The BC-based television and radio broadcasting group Okanagan Skeena, for instance, was the off-shoot of a real estate development firm in the province, while Molson’s Brewery backed the advent of Netstar Communications—a pioneer in pay and specialty television services in Canada.

The general trend at them time was to encourage more players and more diversity in television and radio ownership. When bouts of consolidation did occur, it tended to be amongst individual players in single media markets, i.e. through horizontal integration. Conrad Black’s take-over of the Southam newspaper chain in 1996 was a case in point, while the amalgamation of several local and regional television ownership groups in the late 1990s to create a handful of national commercial television networks under common ownership further exemplified the point: CTV, Global, TVA, CHUM, TQS.

While weighty in their own right, these amalgamations did not have a big impact across the media. The CBC still remained prominent during this period, but public television and radio was also being steadily eclipsed by the expansion of commercial broadcasting services. As evidence of this, the CBC’s share of all resources in the television ‘system’ slid from 45 percent in 1984 to a little over a quarter of that amount today (12.5%).

Media conglomerates and vertical integration, of course, were not unknown at this time. To the contrary, their formation was seen by many as embodying the rising force of media convergence. Maclean-Hunter was a good example of just this type of media firm. Indeed, Rogers’ blockbuster take-over of Maclean-Hunter in 1994 was held up as the harbinger of a new era of convergence and marked the ascent of the vertically integrated communications and media conglomerate in Canada.

A half decade later, the second such firm in Canada emerged after Quebecor went on a fin-de-siècle buying spree to acquire the Sun chain of newspapers in 1999, the largest cable company in Quebec, Videotron, in 2000, and the French-language commercial television network, TVA the next year. Overnight, the former regional newspaper publishing and printing company had been remade into a communications and media conglomerate that towered over the television, cable television, newspaper, magazine, book and music markets in Quebec.

Bell Canada Enterprises (BCE) was the next to pursue the convergence holy grail. While BCE has been a communications colossus throughout the period covered by this report, it was not in the media business proper and had, in fact, historically been prevented by its charter and by law from being so. This changed in 2000, however, when BCE took advantage of the Chretien Government’s relaxed cross-media ownership rules to acquire the national English-language CTV television network, a stable of pay television services, and the Globe and Mail newspaper. This experiment in convergence, however, was short-lived, as Bell sold-off its stakes in CTV and The Globe and Mail in 2006, demonstrating in the process that convergence was by no means inevitable, despite government policies to promote it, and industrial interests like BCE that seemed to be forever enthralled by it.

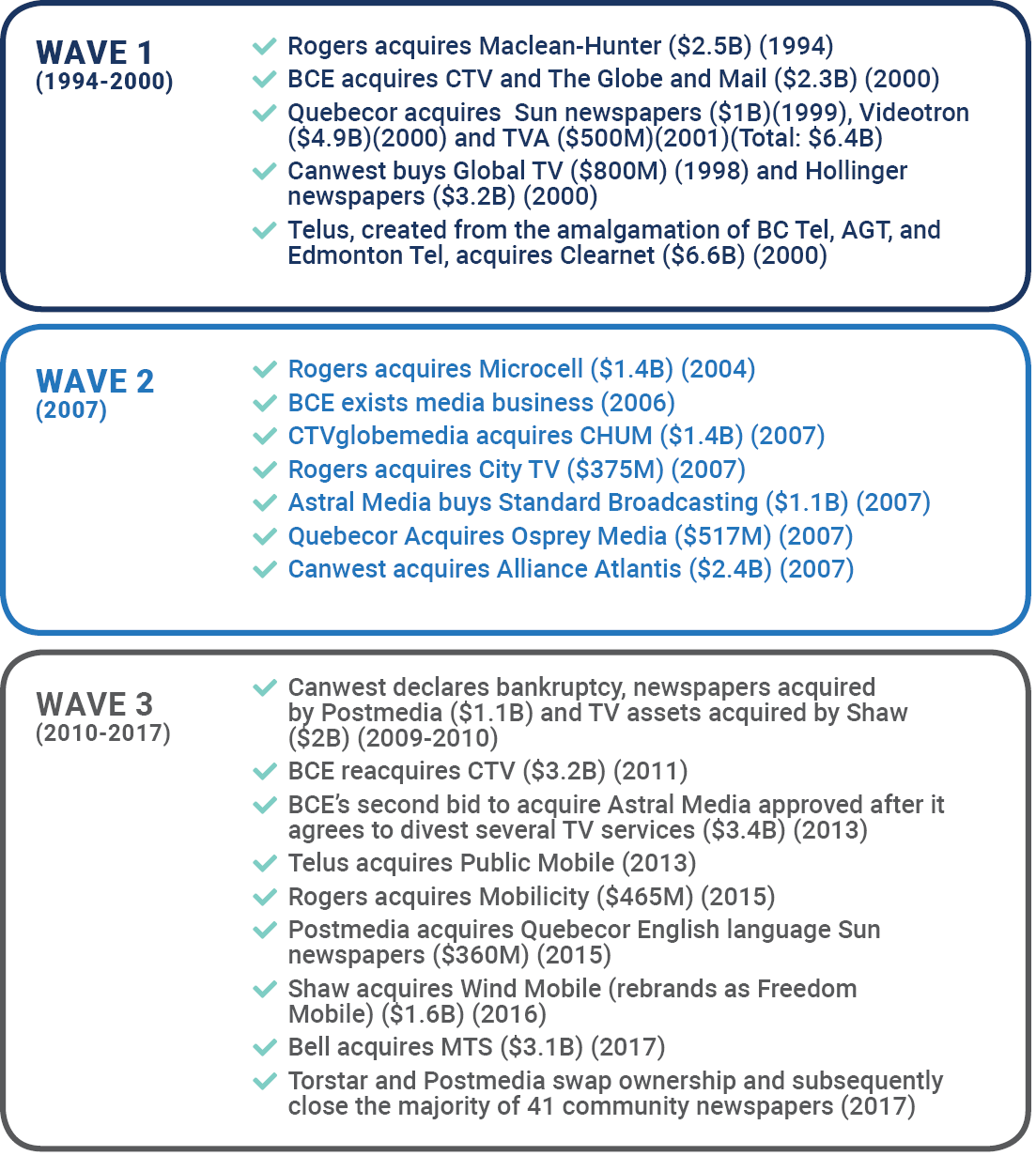

Whereas gradual change defined the 1980s and early-1990s, things shifted abruptly after the mid-1990s and carried on into the 21st century when three waves of consolidation swept across the telecom, Internet and media industries. Figure 2, below, reviews some of the major mergers and acquisitions that have reconfigured the communications, Internet and media landscape in Canada over the last quarter-of-a-century.

Figure 2: Major Communications & Media Ownership Changes in Canada, 1994-2019

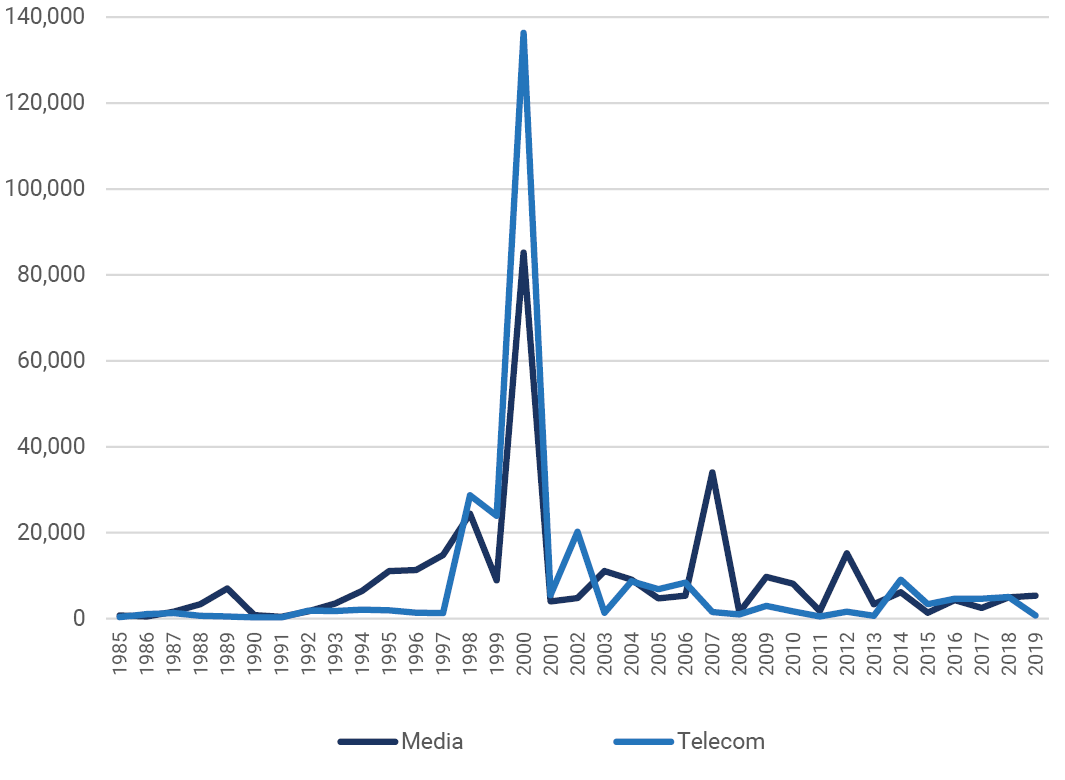

The waves of capital investment that drove consolidation across the telecom, media and Internet industries during these different phases is illustrated in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Mergers and Acquisitions in Telecoms & Media, 1985–2019 (Mill$)

Source: Redefinitive (formerly Thomson Reuters). Dataset on file with author.[33]

As Figure 3 illustrates, mergers and acquisitions rose between 1994-1996 but then soared to never-since-repeated heights before collapsing as the dot.com bubble burst in 2000. These processes reflected and embodied the business, political and regulatory climate of the time and the greatly expanded role of finance capital investment in the economy generally and in the telecoms, Internet and media sectors specifically.

After the euphoria of the dot.com era melted away, several companies stumbled on for several years before collapsing, either outright (e.g. Hollinger Newspapers, Craig Media, 360Networks) or jettisoned their ill-conceived attempts at communications and media convergence (e.g. BCE). At the same time, well-established players stepped in to pick up the wreckage, as Canwest did, for example, with respect to the Hollinger Newspaper chain and Craig Media (the A-Channel network), and BCE did with respect to 360Networks. In addition, two mobile wireless operators that had been created in the mid-1990s to compete with the national mobile wireless duopoly of the time—Clearnet and Microcell—were acquired by Telus in 2000 and Rogers in 2004, respectively, thereby putting an end to this early era of mobile wireless competition.

In broadcasting, the then-burgeoning pay television and newspaper publishing industries in Canada came in for a round of consolidation in the second half of the first decade of the 2000s. Four transactions, all of which took place in 2007, stood out:

- Canwest’s acquisition of Alliance Atlantis, one of Canada’s largest pay and specialty TV services at the time (CRTC, 2007).

- Astral Media’s acquisition of Standard Broadcasting, the third largest commercial radio ownership group (see CRTC, 2007).

- The complicated make-over of CTV that took place as Bell Canada exited the media industry and the newly formed CTVglobemedia took over Bell’s interest in CTV while also joining forces with Rogers to acquire CHUM—also one of the country’s largest and most iconic TV and radio broadcasters at the time (CRTC, 2007; CRTC, 2008)

- Quebecor acquired Osprey, a significant newspaper publisher operating largely in Ontario and Quebec.

By the time 2007 drew to a close, nearly all of the significant independent television, radio and newspaper publishing groups in Canada—Alliance Atlantic, Standard Broadcasting, CHUM, and Osprey—had been swallowed by a handful of national media conglomerates. It was a significant milestone marking the point at which the audiovisual and publishing media landscape across the country had been completely overhauled through a sweeping process of cross-media ownership consolidation within the span of just a year. As for the CRTC, wherever its mandate was engaged with respect to these transactions, it offered its blessing and little to no sense that it could, if it wanted to, serve as a countervailing force to the processes of market consolidation.

This run-of-events once again thrust concerns with media concentration back into the spotlight. In response, parliamentarians and regulators convened another round of inquiries between 2003 and 2008: (1) the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage, Our Cultural Sovereignty (2003); (2) the Standing Senate Committee on Transport and Communications, Final Report on the Canadian News Media (2006); (3) the CRTC’s Diversity of Voices report in 2008. Yet, as was the case with earlier such reviews, none of these inquiries amounted to much, and the CRTC’s weak Diversity of Voices may have even sent the signal that the Commission was loath to do much to stop consolidation and, moreover, that it believed that cultivating national champions in the communications and broadcasting industries was good public policy.

That stance certainly fits well with what followed next when, circa 2007 to 2013, commercial television was essentially taken over by three vertically integrated, national communications and media conglomerates: Rogers, Shaw and Bell. They were matched in Quebec by the regional communications and media conglomerate, Quebecor, a company that had been assembled at the turn-of-the-21st Century and, by this time, towered over the cable television, broadcast television, French-language pay television services, newspapers, magazines, book publishing and recorded music industry in the province.

This process of grafting television onto the immensely larger communications industry took place in, more or less, three steps between 2007 and 2011. The first step occurred in 2007 when Rogers—already a vertically integrated company on account of its history in radio broadcasting and its acquisition of Maclean Hunter in the early-1990s—acquired the City TV network of six stations and roster of pay television services after it took over part of the CHUM operations, as we saw a moment ago.

Three years later, Shaw, the Alberta-based cable communications giant that had been mainly operating in Western Canada up until this point, acquired Global TV from the bankrupt Canwest. Like Rogers, Shaw already had a modest stake in pay television services, television production (Nelvanna) and radio broadcasting through its ownership of Corus Entertainment (acquired in 1999). With its take-over of Canwest, however, Shaw was transformed into a major vertically integrated communications and media conglomerate with a stable of nine local television stations in major cities across the country, fifty-three radio stations and thirty pay television services.

The next phase in this process revolved around BCE’ resurrection of its communications and media convergence vision. Over the next three years, Bell re-acquired CTV in 2011. A year later, Bell acquired a joint-ownership stake (37.5%) with Rogers (37.5%) and Kilmer Sports (25%) in Maple Leaf Sports and Entertainment, giving it part ownership of the Toronto Maple Leafs, the Toronto Raptors, the Toronto Blue Jays, the Air Canada Centre in Toronto, and three digital pay television services: Leafs TV, NBA TV Canada and GolfTV. Lastly, in 2013, Bell acquired Astral Media—the largest independent pay and specialty television service and radio broadcaster at the time (together with Astral’s rights to premium pay television content, i.e. HBO Canada).

By 2013, Bell was not only the largest communications company in Canada but also the biggest media content company. It still is, by far, with thirty local broadcast television stations, thirty-nine pay and specialty television services, the Crave streaming television service, and 105 radio stations in fifty-four cities nationwide (see the TV Services Ownership sheet in the CMCRP Workbook).

Once the dust had settled, the network media economy in Canada had been completely transformed and its fate harnessed to four vertically integrated communications and media conglomerates:

- Bell owned the CTV network, forty-plus pay television services, and the country’s largest commercial radio network;

- Rogers owned City TV, more than a dozen pay television services, and the second largest commercial radio network in Canada;

- Shaw owned the Global TV, a roster of fifty pay television services, and Canada’s third largest commercial radio group;

- Quebecor maintained its longer standing ownership of the French-language TVA network, a dozen pay television services, two French-language newspapers (i.e. Le Journal de Montréal and Le Journal de Québec) and the English-language Sun newspaper chain.

In comparison to these processes that bound the media content sectors of the network media economy to the communications industries, there was a comparative lull in the telecoms industry for the next several years after having engaged in its own orgy of consolidation in the 1990s and first five years of the 21st Century.

Indeed, it appeared as if the trend was toward diversification, when Industry Canada used the 2008 AWS spectrum auction to support the entry of a handful of new firms into the national mobile wireless market. This expansion of players, however, was beaten back when Telus bought the independent mobile wireless company, Public Mobile, in 2013, initiating a wave of reconsolidation. Bell added to the consolidation momentum in the telecoms industry the next year when it acquired the remaining ownership stakes in Bell Aliant it did not already own (Bell Aliant was a holding company that owned and operated telecoms systems in the Atlantic provinces). Rogers joined the fray in 2015 when it acquired (and then dismantled) one of the few remaining independent mobile wireless providers, Mobilicity.

Shaw further added to the consolidation trend in 2016 when it acquired Wind Mobile (since rebranded Freedom Mobile). This transaction was especially significant because it eliminated the last stand-alone mobile wireless network operator in the country. This, in turn, was a significant blow to competition given the tendency for the existence of stand-alone mobile network operators in a market to drive down the high cost of a wireless subscription and the cost of data while generally offering more generous data allowances (see the mobile wireless sector below for further details)(on these points, see Rewheel/Digital Fuel Monitor, 2020).

The Competition Bureau’s approval of Bell’s take-over of MTS in 2017 girded the trend and raised questions about the Bureau’s resolve on such matters. Its own staff analysis showed that oligopolistic behaviour by the big three national carriers—Bell, Rogers and Telus—is hobbling the availability of high quality, affordable mobile wireless services, especially in areas where there is no strong independent rival. Despite its own clearly presented conclusions regarding the likely drawbacks that would follow from the deal, however, the Competition Bureau gave the green light to Bell’s takeover of MTS, thereby removing Manitoba from the list of provinces and regions with a strong independent operator (see our report opposing the deal).

The Remarkable Rise of Vertically integrated Communications and Media Conglomerates in Canada, 2010-2019

The significance of the transformations discussed above not only led to higher levels of concentration within specific sectors but, more importantly, they yielded a specific type of company that now sits at the apex of the network media universe in Canada: the vertically integrated communications and media conglomerate. Levels of vertical integration soared between 2010 and 2013, and are now exceptionally high relative to historical conditions and in relation to the United States and internationally.

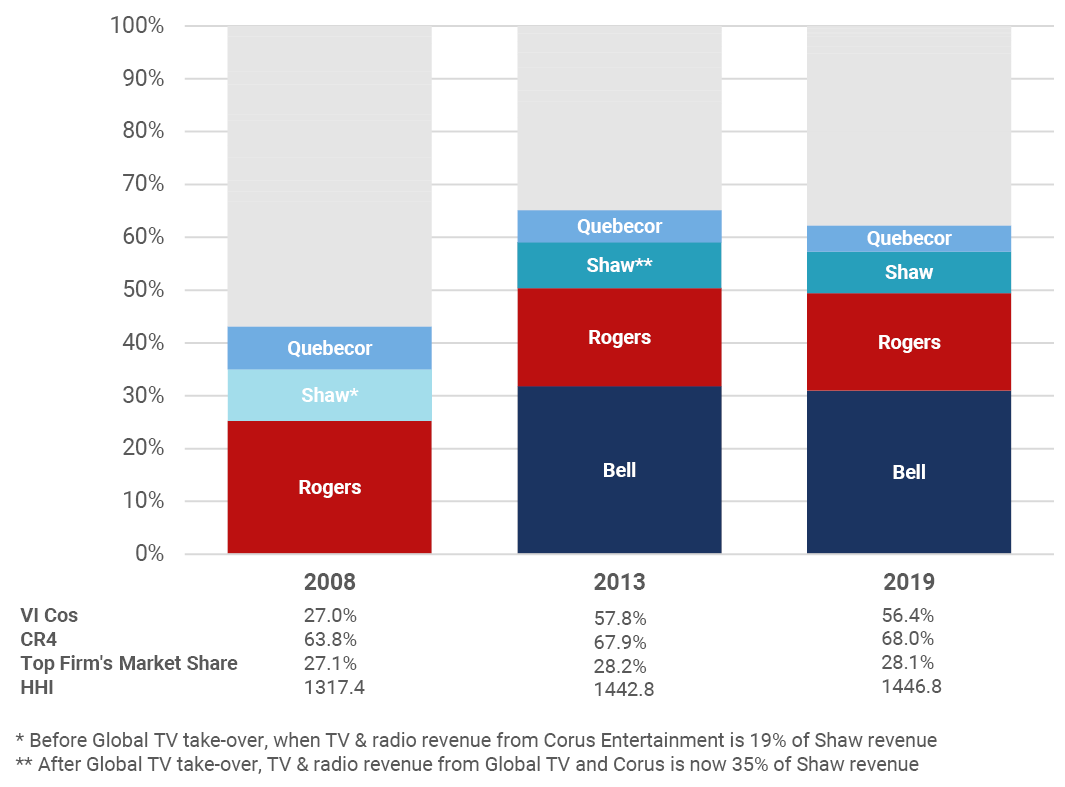

Figure 4, below, illustrate the steep increase in vertical integration that occurred between 2007 and 2018, with most of that change taking place between 2010 and 2013 when Shaw and Bell took over Global TV and CTV’s large portfolio of television and radio services, respectively.

Figure 4: The Rise of Vertically Integrated Communications and Media Conglomerates, 2008, 2013 and 2019

Sources: see the “Top 20 w Telecoms” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook.

As Figure 4 illustrates, between 2008 and 2013, vertically integrated companies’ share of the network media economy in Canada more than doubled to levels that they have stayed the same ever since. By 2019, four such conglomerates accounted for 56.4% revenue across the network media economy: Bell (CTV), Rogers (CityTV), Shaw (Global) and Quebecor (TVA).

The levels of vertical integration in Canada are not just high by historical standards, but relative to those in the United States and internationally. In the most comprehensive and recent review of media ownership and concentration, Who Owns the World’s Media (Noam, 2016), Canada had the third highest level of vertical integration out of the 28 countries examined.

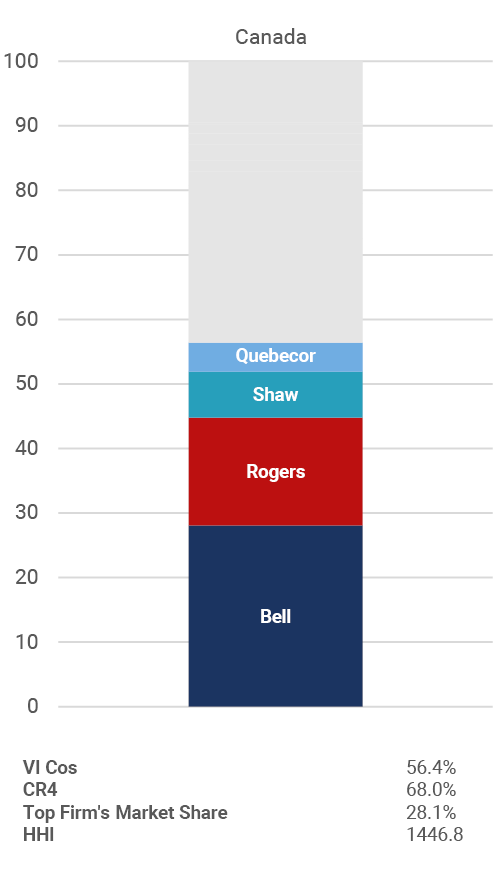

Figure 5 below illustrates the point with respect Canada and the United States for 2019.

Figure 5: Vertical Integration in Communication and Media Sectors – United States vs Canada, 2019

Sources: see the “Top US Telecom + Mediacos” and the “Top 20 w Telecoms” sheets in the CMCRP Workbook Note: Charter and Liberty in the United States are treated as being commonly owned because of John Malone’s controlling shareholder stakes in each company.

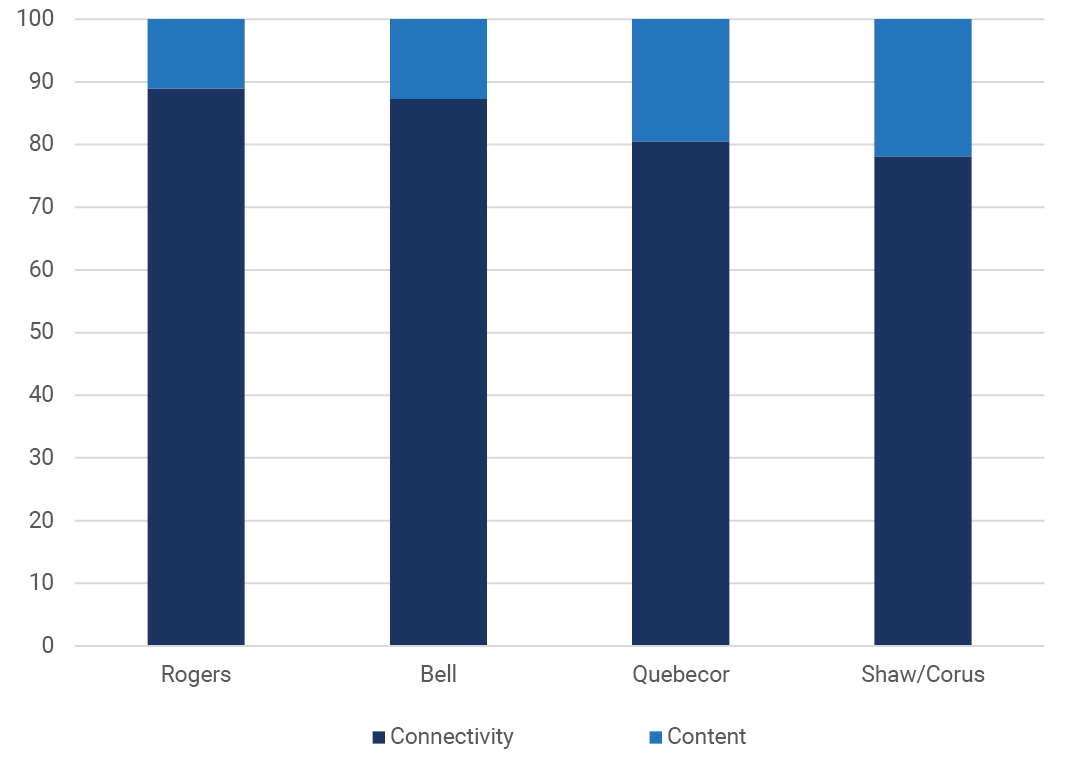

Before 2010, vertically integrated firms were modest in stature and exceptional, but afterwards the top four such firms came to occupy centre stage: Bell, Rogers, Shaw and Quebecor. For each of these firms, control over communications infrastructure is the pivot around which the rest of their operations—and the media economy—swivels. Although their stakes in audiovisual media services are extensive, they are also modest in comparison to their communications services. For Quebecor, Shaw, Bell and Rogers, 78-89% percent of their revenues flows from this side of their business rather than from media content creation. Figure 5 below illustrates the point.

Figure 6: Connectivity vs Content within Canada’s Vertically integrated Telecoms and Media Companies, 2019 (Ratio by Revenue)

Sources: see the “Top 20 w Telecoms” sheet in the CMCRP Workbook.

Another way to put this is that audiovisual media in Canada have largely become ornaments on the national carriers’ corporate edifice. They are strategically important, but their real purpose seems to be to drive the take-up of the companies’ vastly more lucrative wireless, broadband Internet, and cable, satellite and IPTV services. That Bell owns roughly half of the services on its Mobile TV roster, for example, illustrates the point.[34]