Growth and Upheaval in the Network Media Economy in Canada, 1984-2019

Contents

Summary of key findings and insights

The Network Media Economy in Canada: Contemporary Trends and Ongoing Policy Debates

The Telecoms and Internet Infrastructure Sectors: Bandwidth is King, Not Content

From Plain Old Telephone Service to Broadband Internet Access and Internet Protocol TV

Broadband Policy, Politics and Public Interests: One Step Forward, Two Steps Back?

As Internet Advertising Soars, Total Advertising Spending Slumps

The Rumoured Death of Television is Much Exaggerated

Pay and Specialty (Subscription) TV

Online Subscription and Download Audiovisual Media Services (AVMS)

The Total Television Landscape in Perspective

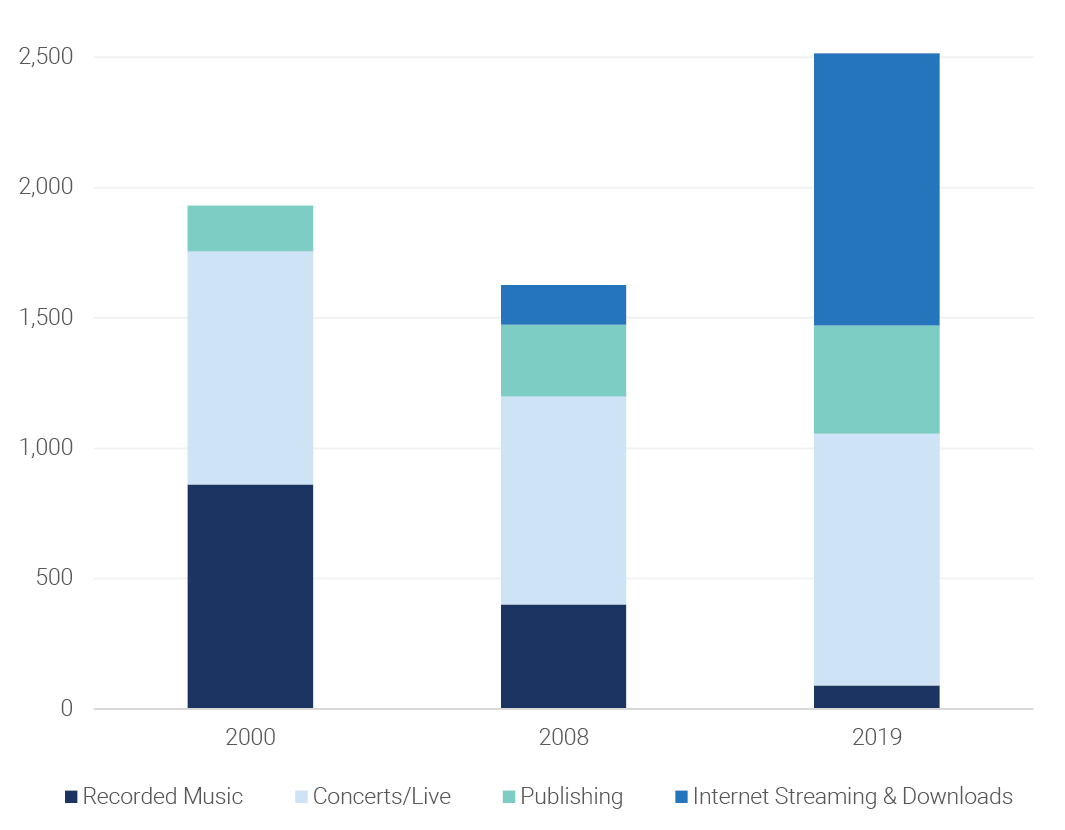

Remaking the Music Industry: From Ruin to Recovery

Newspapers and Magazine Publishers in Peril

ANALYSIS – Some Reflections on Journalism, Public Subsidies and Public Goods

Some Concluding Observations on the Political Economy and Power of Communication and Culture Policy

Every year the Canadian Media Concentration Research Project puts out a series of reports on the state of the telecoms, Internet, and media industries in Canada. This is the first installment in this year’s series (previous versions can be found here).

This report examines the development of the media economy over the past thirty-five years. Since beginning this project a decade ago, we have focused on analyzing a comprehensive as possible selection of the biggest telecoms, Internet and media industries (based on revenue) in Canada, including: mobile wireless and wireline telecoms; Internet access; cable, satellite & IPTV; broadcast television, specialty and pay television services as well as Internet-based video subscription and download services; radio; newspapers; magazines; music; Internet advertising; social media; operating systems; browsers, etc.

Beginning last year, we made some fairly dramatic changes by trying to capture a broader range of audiovisual media services that are delivered over the Internet beyond online video subscription and download services and Internet advertising. The new sectors brought into our analysis since then include:

- Online gaming, gaming applications, game downloads or in-game purchases (Digital Games);

- App stores, in particular Google Play and Apple Appstore;

- Music downloads and streaming music subscriptions.

We classify these sectors as the digital audiovisual media services, or digital AVMS for short, a category that also includes online video subscription and download services such as Netflix, Crave, Club illico, CBC Gem, Apple iTunes and Amazon Video. We also distinguish them from their legacy counterparts (e.g. broadcast TV, specialty and pay TV, radio, music, newspapers, and magazines) that do not depend on Internet aggregation and distribution as a core part of their business models and activities.

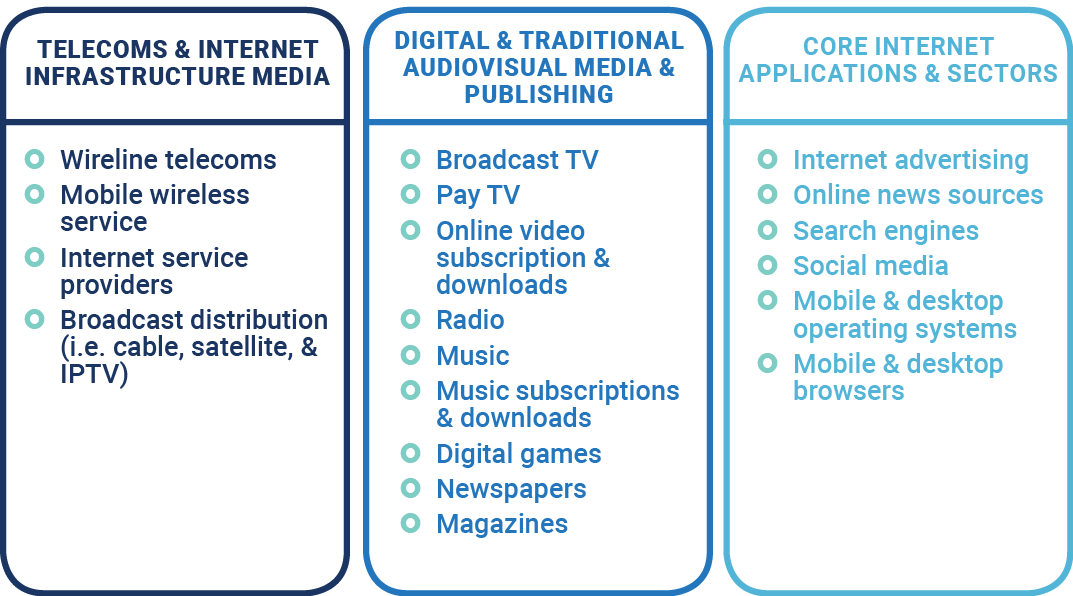

Figure 1 below depicts the segments of the digital and traditional media industries that collectively comprise what we call the network media economy.

Figure 1: The Network Media Economy in Canada–What the CMCR Project Covers

The research method that we use is simple: we begin by examining the individual components of the network media economy (i.e. the sectors indicated in Figure 1 above). This involves collecting, organizing, and publishing stand-alone data for each media industry individually. We then group related, comparable industry sectors into three more general categories: the “telecoms and Internet infrastructure media”, the digital and traditional AVMS and finally, “core Internet applications and sectors”. Ultimately, we combine them all together to get a bird’s-eye view of the network media economy, taking care to explain how the sectors interact with one another and fit together to form the network media economy as a whole. We call this the scaffolding approach.

Following this approach ensures that we start with a clear, precise definition of “the media” so that readers know what is included in our analysis and what is not. It also helps to ensure that apples-to-apples comparisons are being made with other studies and research reports, both within Canada and internationally. Too often, debates in this area proceed without such an explicit definition. As a consequence, some researchers cast a conceptual net so wide that the defining details of specific media are difficult to discern in their analysis, while others cherry pick sections of the media that support the story they want to tell.[1]

The scaffolding approach not only allows us to focus on the details and relative scale of the various individual segments of the network media economy, but it helps to see how they all fit together, and to understand where the many different actors fit within each sector and the network media economy as a whole. In concrete terms, this allows us to see how major domestic actors stack up when measured against the activities of major global players within the Canadian context. Lastly, this approach reveals which of these industries are growing, which are stagnating, which are in decline, and which appear to be recovering after years of misery. Table 1, below, offers a high-level snapshot of where things stood at the end of 2019.

Table 1: The Growth, Stagnation and Decline of Media within the Network Media Economy, 2019

Beyond the overall direction of developments within specific sectors over the past year, the report identifies several major ongoing developments in Canada’s network media economy:

- The overall story is one of ongoing growth, upheaval and increased complexity for the network media economy rather than a Cassandra story of widespread crisis.

- Despite a continued focus on advertising revenue in much communication and media scholarship, public debates and policy circles, the reality is that revenue from subscriber fees and direct purchases are at the centre of the media economy. Indeed, revenue from subscriber fees and direct purchases outstrip advertising revenue by a nearly 5 to 1 ratio. It is also critically important to note that the total scope of advertising spend for all media has been relatively fixed over time, and actually fell or stagnated for much of the last decade in inflation adjusted terms, on a per capita basis and relative to the size of the overall economy. At the same time, advertising revenue continues to shift to Internet behemoths such as Google and Facebook. This means that those sectors of the media and firms dependent on advertising are battling some of the world’s largest Internet companies to retain a share of relatively stagnant pool of advertising dollars.

- Contrary to narratives overly focused on broadcast television, Canada’s audiovisual media services market continues to grow swiftly, bolstered by a raft of online video services. The story is even stronger for investment in Canada’s film and television production sector, which has nearly doubled in the past decade.

- Rather than looking to historical approaches to broadcasting regulation, governments should heed experiences in telecom and banking regulation to inform their policy responses to the network media challenges of today. These approaches take seriously the need for structural and behavioural regulation of platforms, and potentially extending fiduciary duties to the inputs of the digital economy.

Ultimately, our goal is also to bring a wealth of historically- and theoretically-informed empirical evidence to bear on contentious claims about the media industries. Within a context where the role of policy and regulators looms large, knowing both the details and the broad sweep of the network media economy allows us to make informed contributions to the debate from an independent standpoint. This is especially necessary given the ongoing Parliamentary responses to recently concluded reviews of, for example, the Telecommunications Act, Broadcasting Act, Copyright Modernization Act and Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act (PIPEDA). In light of such realities we need the best, most independent view of the landscape that we can get, and that is what we strive to do with our annual reviews and regular updates to our public data sets.

This informed and independent view is also a key input to what could be considered the preeminent debate in this area of policy, the role of digital giants in the future of Canadian and global media markets. Indeed, in the last four to five years alone, there have been at least eighty public policy examinations of the digital platforms worldwide, as governments from India and Australia to the Netherlands, the United States and Canada all grapple with the potentially far-reaching implications of these new actors and their impacts on journalism, the media, economy and society (Winseck & Puppis, 2020).

Fundamental questions about whether the very business models and extraordinary market power of Internet giants such as Facebook and Google are inherently primed for nefarious possibilities[2], regardless of their owners’ best intentions to connect the world and foster community, are now on the table like never before.

Questions are also being raised about whether these entities have become too big to effectively govern—either through self-regulation or by existing democratic institutions[3]. As a general principle, unless the rules shaping such companies’ conduct are guided by duly constituted legal and democratic oversight by parliaments, the courts, or administrative agencies—as was the case for the recent changes to the Canada Elections Act—demands for the digital platforms to better govern themselves will likely make their “black box” character even more opaque than they already are. That Amazon, Facebook or Google could be broken up just like AT&T was in 1984 is no longer a far-fetched idea (Khan, 2017; Vaidhyanathan, 2018; United States Judiciary Committee, 2020; Wu, 2018). Indeed, the issue is no longer if the platforms and Internet content will be regulated but when and how they will.[4]

We are fully supportive of concerns regarding the scale of these companies, their clout, and the threats that they pose to the Internet, some media, democracy and society. We are also fully supportive of the idea that a whole new generation of Internet regulation may be needed to regulate them for precisely these reasons.

However, our analysis also suggests that claims that the Internet hypergiants’ fortunes are being made by cannibalizing the revenue that journalism and the music, movie, television and publishing industries need to survive should be met with a healthy dose of skepticism. There is also a need to be vigilant that the push for a new generation of Internet regulation does not just translate into harnessing the Internet-centric communications and media arrangements of today to protecting approaches to broadcasting regulation and cultural policy of the past. There is also ample reason for concern that the tough structural and behavioural regulatory remedies that are needed to counteract problems of consolidation at every level of the communications, Internet and media ecosystem, and the unlimited personal data harvesting models—that fuel the commercial Internet services but which are proving to be so corrosive of people’s trust, social relationships and democracy, are thoroughly addressed—rather than the pronounced tendency at present to skip those steps in favour of directly regulating Internet content in a misdirect gambit to solve all of society’s perceived ills by cleaning up the Internet and so-called “harmful content” online.[5]

To help understand this tangled knot of issues we need to better appraise where the Internet giants currently stand within Canada. And in so doing, our first question needs to be, of course, we know that these entities loom large, but how large and how will we know?

Our data show that the US-based Internet giants are consolidating their dominance of digital advertising markets in Canada and becoming increasingly dominant across the advertising landscape as a whole. Indeed, the shift to the “mobile Internet” has helped Google and Facebook, in particular, to consolidate their lock on both online advertising and, increasingly, advertising spending across all media, as we will show later in this report. In addition, as the global Internet giants increasingly aggregate and distribute media and cultural content, existing media groups are becoming more platform-dependent, potentially jeopardizing their own economic, technological and cultural autonomy for uncertain benefits (Nieborg & Poell, 2018; Myllylahti, 2019). All of this is critical to comprehending the bleak place in which many advertising-based media now stand.

However, while the growing clout of Internet hypergiants such as Google and Facebook is unmistakeable, it is a mistake to generalize from the digital duopoly’s dominance of the Internet advertising market in Canada to the $91.3 billion network media economy writ large. The same applies globally. Indeed, treating developments in the advertising-based sectors as representative of the overall direction of the industry obscures the reality that these sectors constitute a small and receding proportion of the network media economy as a whole. Moreover, while the influence of the big five digital platforms—i.e. Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft, aka GAFAM—and Netflix is significant, within countries (Canada in particular) they continue to be outstripped by a large margin by the biggest national telecommunications and media groups, as this and the next report in this series will show.

Ultimately, the media’s place in the economy, society and our everyday lives is changing dramatically and is currently up for grabs in ways seldom seen. Some communication historians call times like these a “critical juncture” (McChesney), or a “constitutive moment” (Starr), when decisions made will become embedded in technology, markets and institutions, and then press down on us, for perhaps a century or more if the lessons of “the industrial media age” offer any guide to the contemporary debates surrounding the “Internet” or “digital media age”. The CMCR Project does its best to engage with such realities in a bid to help secure the communication and media that we need and deserve.

- The network media economy has more than quadrupled in size, from $19.4 billion in 1984 to $91.3 billion last year, and continues to grow at a quick pace overall.

- Mobile wireless and Internet access services continued to grow briskly, as revenues rose to $29.2 billion and $12.7 billion, respectively; while revenue for cable, IPTV and satellite TV continued to slide to $8.3 billion in 2019. The communication networks that connect people to one another, to the Internet, other media and other services across the economy and society—i.e. mobile wireless, Internet access, cable, satellite and IPTV services—accounted for 70% of total revenue for the network media economy last year ($63.5 billion), while the media content sectors take up the rest ($27.6 billion). In short, bandwidth, not content, is king in the network media economy.

- Revenue for digital audiovisual media services (AVMS)—online video, music, gaming and app stores—soared to over $5.6 billion last year. Add Internet advertising ($8.8 billion), and the digital AVMS sectors constituted a $14.4 billion pillar of the network media economy in 2019, or 16% of all revenue.

- As a result of these developments, global actors like Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple, Microsoft and Netflix (the so-called GAFAM+ group of Internet giants) become central figures on the media landscape in Canada. Combined, they had $9.2 billion in revenue last year.

- While communication and media companies in Canada face intensifying competition in digital AVMS as a result, the “big 5” companies in Canada still account for nearly three-quarters of all revenue across the network media economy: Bell, Rogers, Telus, Shaw (Corus) and Quebecor. In contrast, the GAFAM+ group’s combined market share is 10%. As this report also emphasizes, the Canadian situation is unique insofar that all the major commercial TV services are owned by telecommunications firms whose operations span many aspects of the network media economy that go far beyond television and internet advertising.

- Although broadcast television is in dire straits, the TV marketplace is thriving due to the addition of new pay TV sectors over time, including over-the-Internet video services. Total TV revenues soared to $8.8 billion in 2019. Netflix had year-over year average of 6.4 million subscribers and $1.1 billion in revenue in Canada last year. At year’s end, 46% of households subscribed to Netflix (the CRTC reports far larger figures but we are skeptical of its estimates for reasons explained in this report). Record high levels of investment in television and film production continued last year, with total investments of $9.3 billion.

- As a result of downward pressure on total advertising revenue over the past decade and the rise of Internet giants such as Google and Facebook, media sectors that depend primarily on advertising are in crisis, e.g. broadcast TV, radio, newspapers and magazines. Collectively, these sectors have lost $4.9 billion, eight broadcast television stations have gone dark and numerous daily newspapers have been closed or pared back their publishing schedules since 2008.

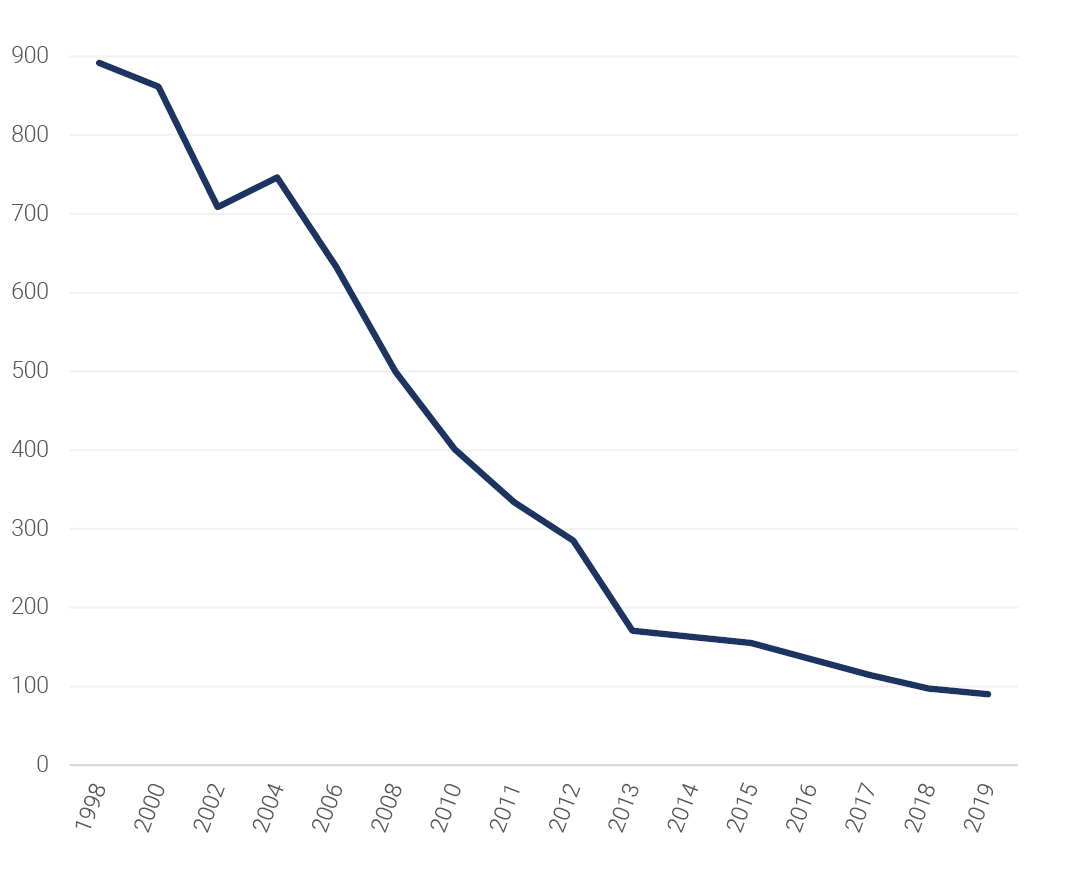

- Newspapers are in turmoil with revenue plunging from a high of $4.7 billion in 2008 to $2.2 billion last year. After rising steadily between 1987 until 2013, the number of full-time journalists has dropped by 30% in the last 6 years. As the number of journalists shrinks, the void is being filled by a vast expansion in the ranks of public relations, advertising and marketing professionals.

For nearly a decade, the CMCR Project has put out an annual series of reports on the state of the telecoms, Internet and media industries in Canada. This report is the first installment in this year’s series. It examines the development of the media economy since 1984, with the “media” defined broadly to include data for nineteen different sectors grouped into three categories, as depicted in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Key Sectors of the Network Media Economy in Canada, 2019

Ultimately, we combine all of these separate sectors together to get a bird’s-eye view of the network media economy.

The aim of this approach—and this report—is to get the best sense we can of how all the different sectors of the telecoms-Internet and media industries have developed over time, to understand the scale and pace of the changes that are taking place, and to see how all of the sectors that we cover fit together to form “the network media economy”. To this end, our approach begins by assembling a multisectoral body of data for the telecoms and Internet access, audio-visual media services and core Internet applications listed in Figure 1 above that collectively comprise “the network media economy”. The objective is also to determine which of these media sectors are growing, stagnating or in decline, while also highlighting those that have found renewed paths to growth, such as the music industry. To this end, the report pays close attention to, for instance, whether online audiovisual media services such as Netflix, Crave and Spotify, and online gaming, apps and app stores (digital games), are cannibalizing established media or helping to expand the size and diversity of the media economy. Other trends such as cord-cutting and cord-shaving are also examined.

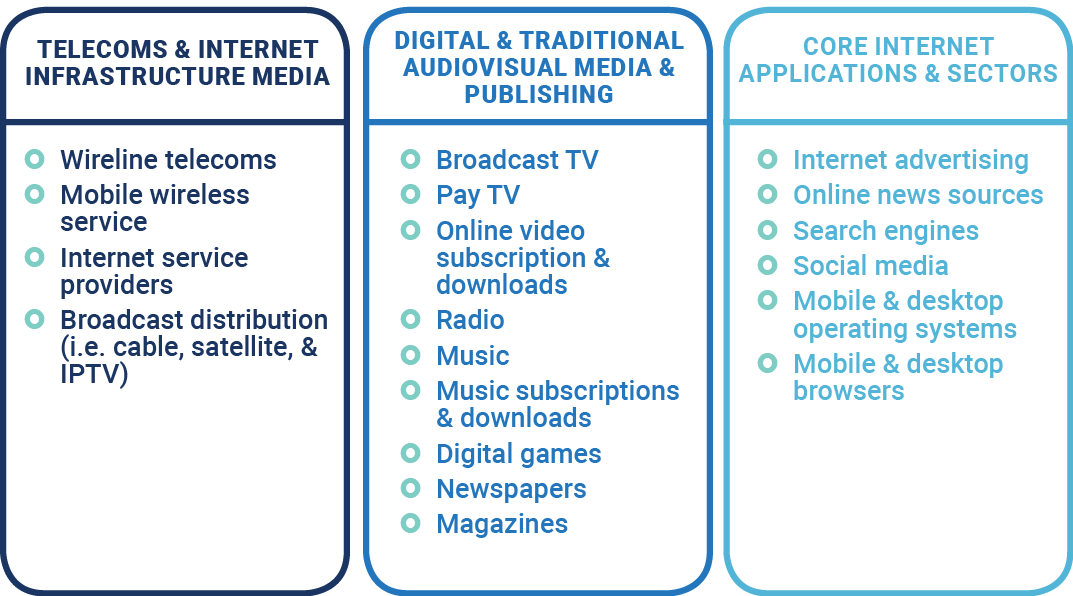

Over the past three-and-a-half decades, the rise of entirely new media sectors–e.g. mobile wireless, Internet access, pay and specialty TV, digital AVMS, and so forth—has added immensely to the size and complexity of the media economy. As a result, between 1984 and last year, total revenue for the network media economy in Canada more than quadrupled from $19.4 billion to $91.3 billion. In contrast to those who claim that the media economy in this country is a pygmy amongst giants, especially relative to the United States, it is important to highlight the fact that of the thirty countries examined in Who Owns the World’s Media, the sum total of which account for roughly 90% of the world’s media revenues, Canada ranked as having the 9th largest media economy (Noam, 2016, pp. 1018-19).

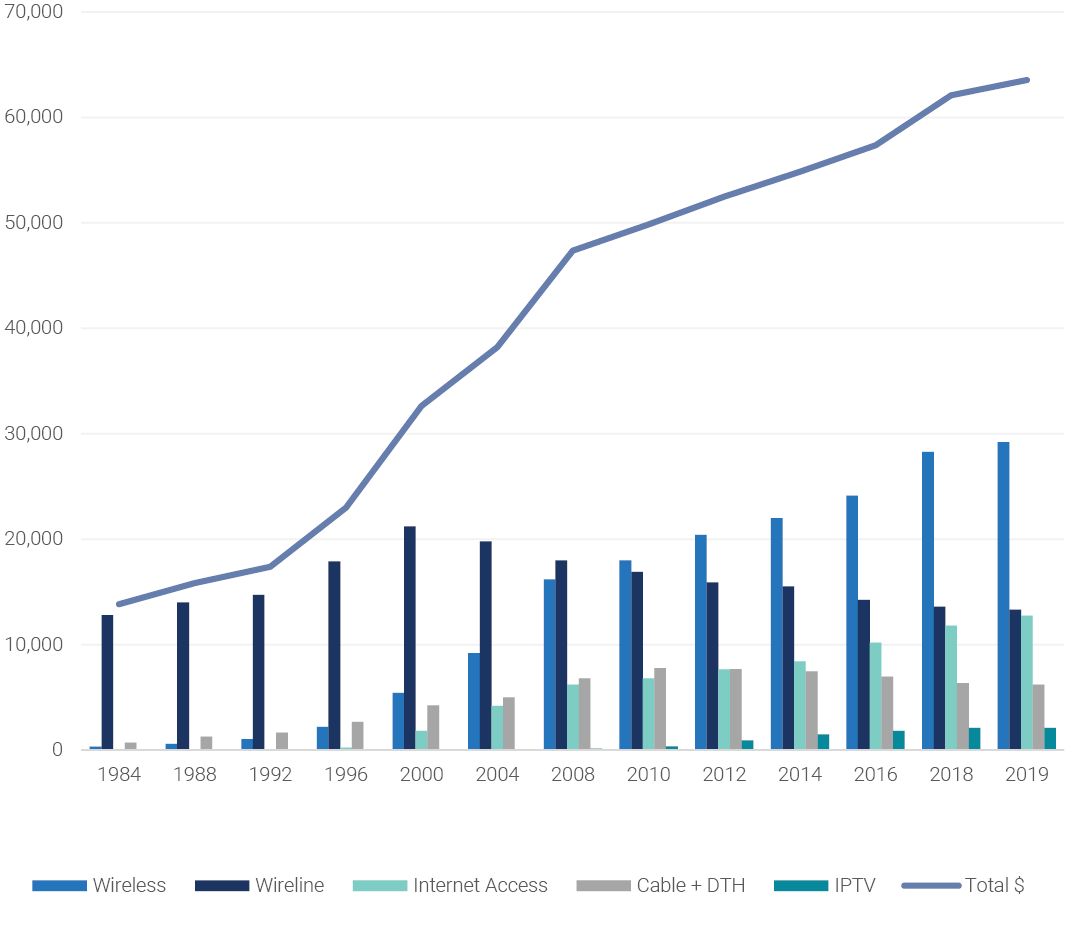

Figure 2 below illustrates the immense growth and transformations of the network media economy in Canada that has taken place over the past thirty-five years.

Figure 2: Development of Telecom & Internet Access Services vs Digital and Traditional Audiovisual Media, 1984-2019 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

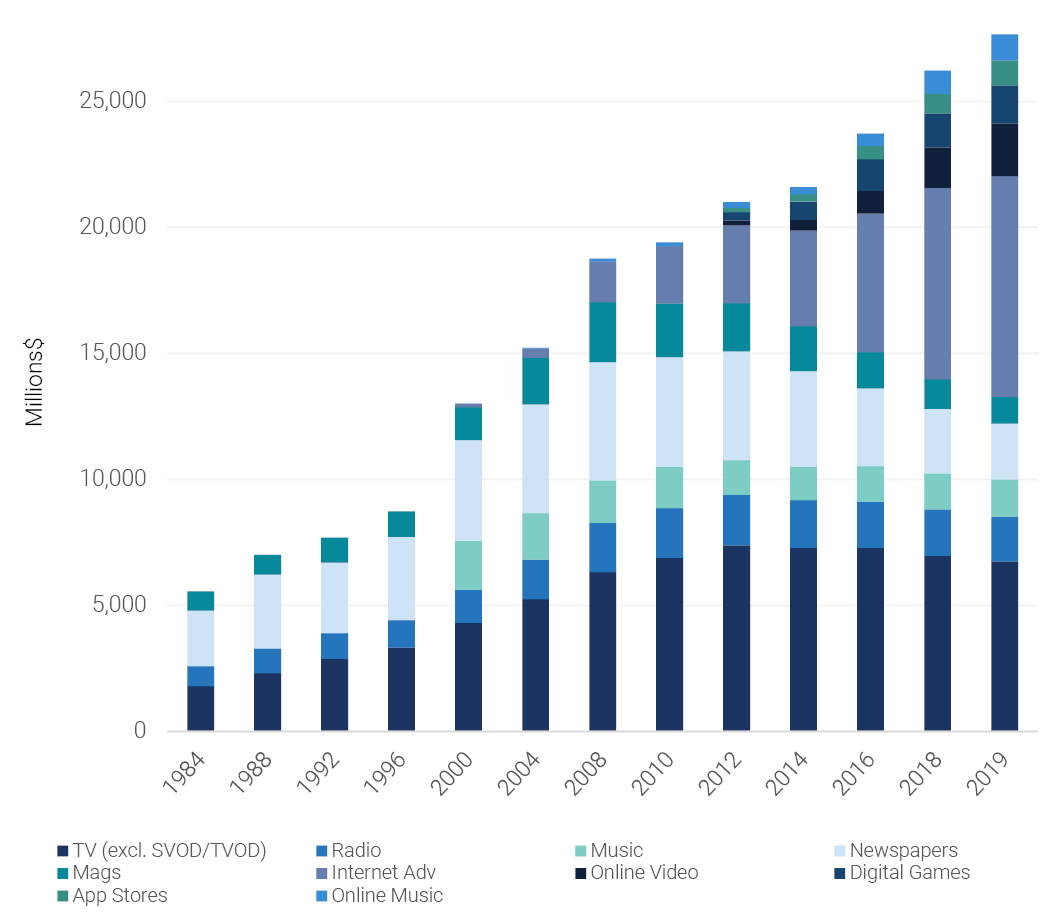

While all segments of the telecoms-Internet and media industries have grown substantially over the long-run, there are several trends and unique differences among them that merit closer attention. A key development identified in this report, for instance, is the extent to which advertising-funded media (i.e. broadcast television, radio, newspapers and magazines) have been steadily eclipsed by the telecoms and Internet access sectors as well as “pay-per” audiovisual media services.[6]

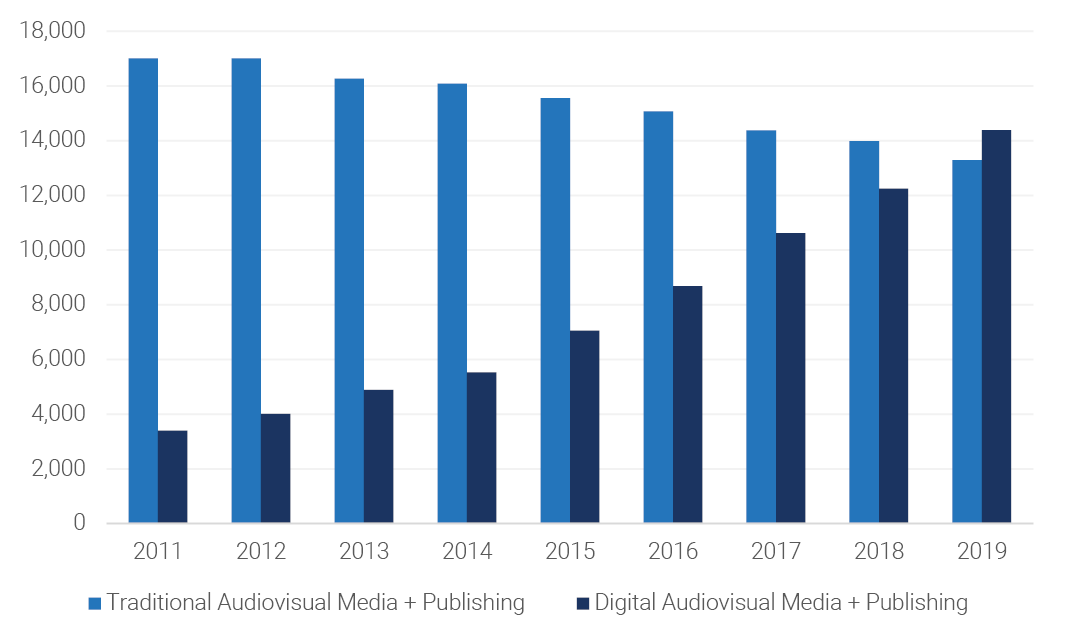

By 2019, the telecoms and Internet access segments—i.e. the pipes, bandwidth, and spectrum-based connections that are now central to effective participation in society, the economy and daily life—had total combined revenues of $63.6 billion, or 70% of all revenue generated within the network media economy, compared to the $15.6 billion generated by the advertising-funded media content industries. These sectors have grown far more quickly than others and are vastly larger than the content side of the media.

Adding to the shift away from ad-supported media, the combined revenue for online video, music, digital games and app stores has soared from $720 million in 2011 to $5.6 billion last year. In fact, combined revenue for telecoms and internet access services as well as subscription-based digital AVMS services now outstrip that of advertising-funded media, including Internet advertising, by a nearly five-to-one ratio. The upshot of these developments is that, in an increasingly Internet- and mobile wireless-centric world, it is network connectivity and subscriber fees, not advertising-supported media, that are king (see Odlyzko).[7]

While there is no doubt that advertising is and will continue to be an important part of the media economy, it only underpins a relatively small and steadily receding subset of the media. Altogether, advertising-funded media account for a modest 17% ($15.6 billion) of the $91.3 billion media economy. Moreover, as we will see, for those media that depend primarily on advertising revenue, a decade of intermittently slow, stagnating and slumping growth after the financial crisis of 2008 has had devastating effects. As a result of this “lost decade”, revenue for broadcast television, radio and magazines, for example, fell by a third, while newspaper revenue collapsed to levels less than half of what they were a little over a decade ago. That all of this took place at the moment when the global Internet giants such as Google and Facebook were coming into their own obviously dealt those media that rely mainly on advertising revenue a serious blow.

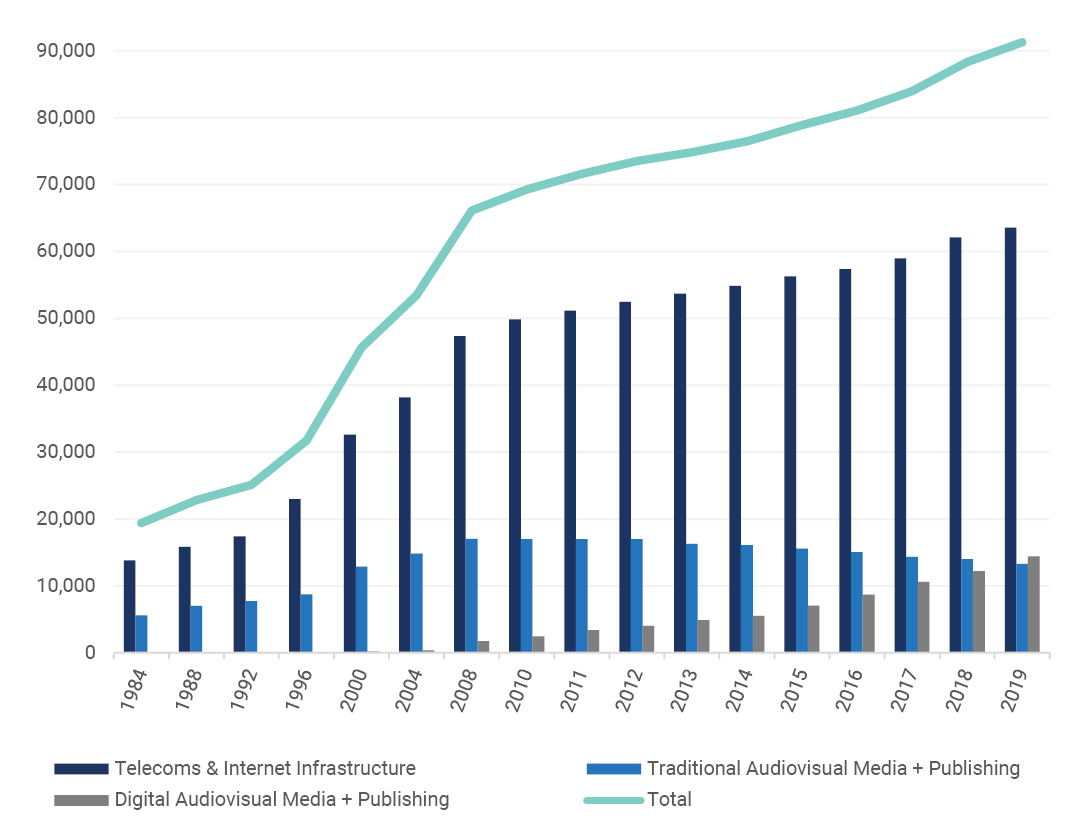

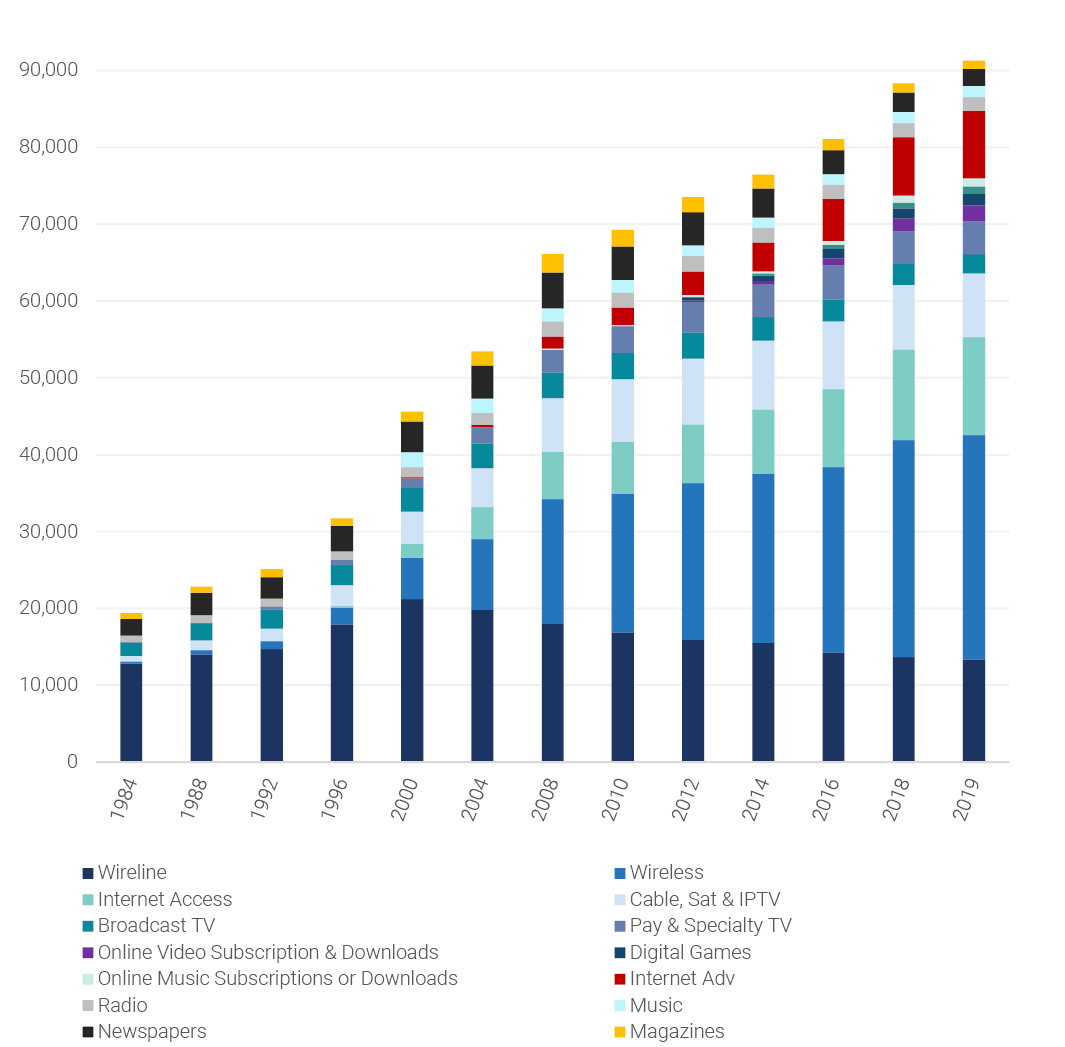

Figure 3 below goes a step further by separately depicting each sector covered in this report and its evolution over time. While all areas of the telecoms-Internet and media industries have grown substantially over the long-run, and changes have been especially fast moving with respect to the digital AVMS sectors in the last five or six years, there are also unique differences among all of them that merit closer attention.

Figure 3: Separate Media, Distinct Evolutionary Paths and the Network Media Economy, 1984–2019 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

To be sure, communication and media companies in Canada are facing intensifying competition with Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple and Microsoft (the so-called GAFAM group of Internet giants) as well as Netflix over this bigger pie as the latter move more deeply into various aspects of the media landscape in Canada than ever before. As they take on a growing role in the aggregation and distribution of media content, for instance, existing media groups are becoming more platform-dependent, at the risk of jeopardizing their own economic and cultural autonomy—and for uncertain benefits (see van Dijck, Nieborg & Poell, 2019; Myllylahti, 2019).

These developments have ignited fierce debates over the impact of GAFAM on the media in Canada—as well as other countries around the world—and are a key driver of calls for aggressive new forms of digital platform regulation that would have been unfathomable just a few years ago. They have also re-ignited long dormant debates over cultural nationalism and technological sovereignty that have not been seen with such intensity since the 1970s and 1980s.

These concerns have been coming to head in the last few years as scholars and policymakers around the world intensely scrutinize a litany of problematic practices arising from the growth of the tech giants. These include: the rise of platform power and “digital dominance”; potential threats to domestic media and cultures; privacy and data protection; “fake news” and hate speech; national sovereignty; the integrity of elections; and antitrust. Consequently, governments from India and Australia to the Netherlands and Canada are all grappling with the implications of these developments. Indeed, there have been at least eighty such public policy examinations in the last five years alone, as one ongoing tally of these inquiries chronicles (Winseck & Puppis, 2019).

Anchor Findings

• Mobile wireless and Internet access services continue to grow at a brisk pace, but Canada’s struggle to meet its targets for universal, affordable broadband internet access continues to be a significant issue.

• Canada’s adoption of IPTV is high relative to other countries, but it severely lags international peers in “fibre to the premises” access, the gold standard for communications infrastructure.

• Following favourable regulatory outcomes related to minimum service standard and net neutrality in the mid-2010s, a change in CRTC leadership has put the future of broadband regulation into question.

The telecoms and Internet access industries have grown enormously, from $13.1 billion in 1984 to $63.6 billion last year. They account for approximately 70% of all revenue, and are thus the fulcrum upon which the media economy pivots. Figure 4 illustrates their development over time.

Figure 4: Revenues for the Telecoms and Internet Access Sectors, 1984-2019 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Wireline”, “Wireless”, “ISPs” and “CableSatIPTV” sheets in the Excel Workbook.

Mobile wireless services have expanded quickly since the turn-of-the-21st century to become a cornerstone of the digital media ecology. They overtook plain old wireline telephone services in 2009 based on revenue, while in 2014 the number of Canadian households subscribing exclusively to mobile services for their voice calling needs exceeded those relying exclusively on landlines for the first time (CRTC, 2015, p. 1). The centrality of mobile wireless services is also underscored by the fact that they are now the largest sector of the network media economy, by far, with revenue having grown nearly six-fold from $5.4 billion in 2000 to an estimated $29.2 billion last year.

The sustained growth of mobile wireless services has tracked an expanding array of devices that people use to connect to mobile wireless networks—a sector that once primarily connected “feature phones” and pagers now provides connectivity to a constantly expanding range of different smartphones, tablets, and connected laptop PCs. As providers begin to debut “5G” networks, it is expected that this array will continue to expand in both scale and scope, with the emphasis shifting even further in the direction of data-based broadband services, rather than the traditional voice-based services that gave mobile services their start. Consistent with this trend, mobile data traffic doubled in Canada between 2012 and 2013, and has continued to grow in the 40-60% range every year since. Cisco projects that mobile data traffic will grow four-fold between 2017 and 2022.

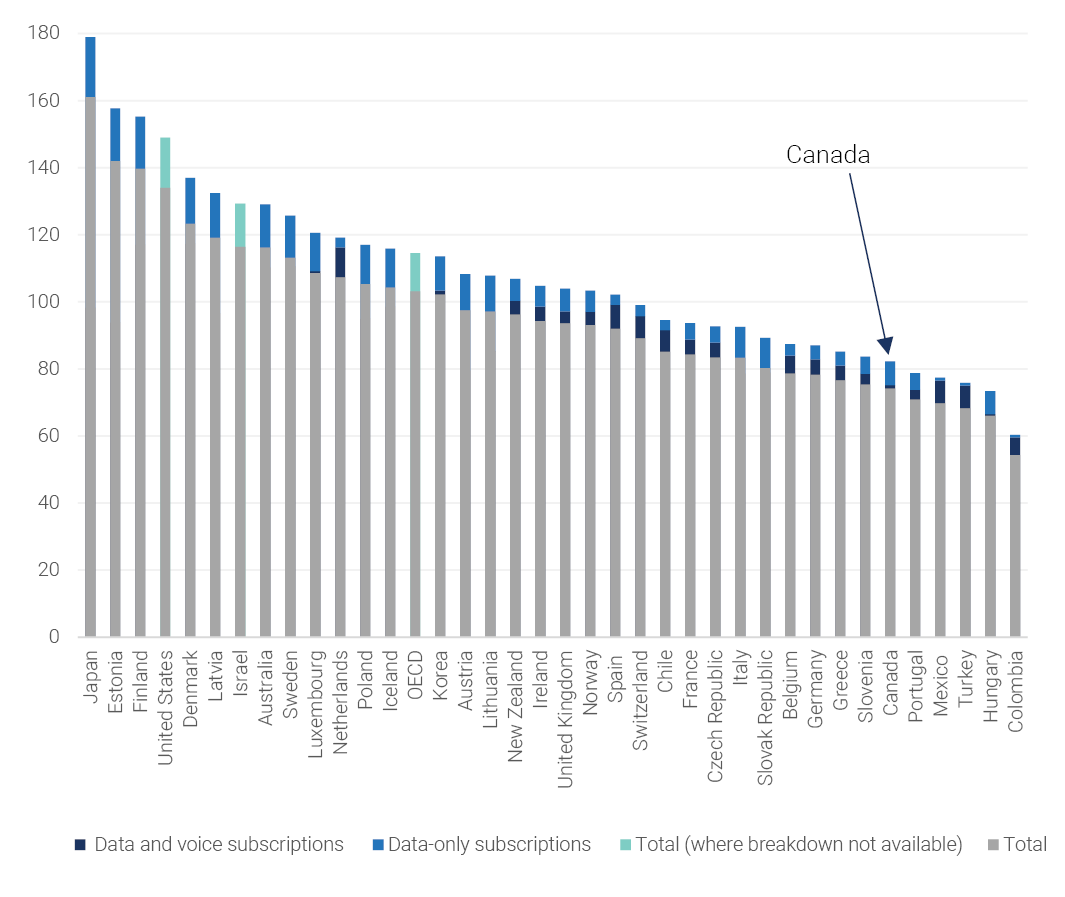

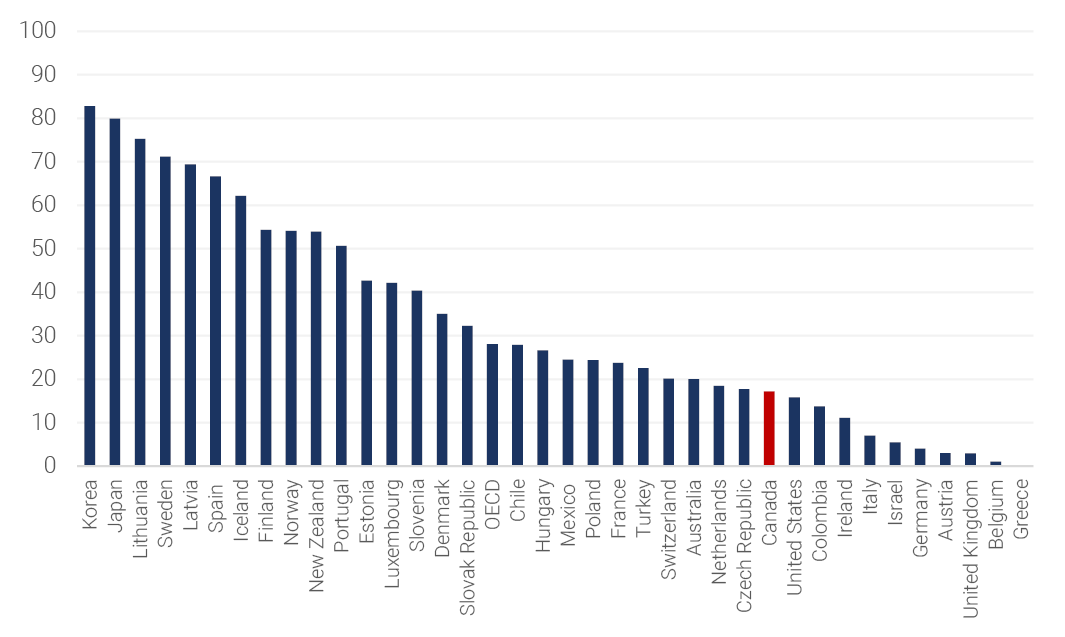

Despite this fast growth, mobile broadband (i.e. the mobile internet) adoption and usage in Canada continues to rank poorly against other OECD countries. Indeed, Canada ranks a lowly 32nd out of 37 OECD countries for broadband wireless penetration as of December 2019—a further drop in rank by one place of where it was last year and at levels well below those in the US, UK, Denmark, Australia, and the vast majority of other OECD countries. Figure 5, below, illustrates the point. Moreover, this is a position that Canada has languished in for a decade-and-a-half (Benkler, Faris, Glasser, Miyakawa, Schultze, 2010; OECD, 2011).

Figure 5: OECD Wireless Broadband Subscriptions per 100 inhabitants, by Technology, December 2019

Source: OECD Broadband Portal.

Like other sectors, revenue growth in mobile wireless slowed post-2008. Already as early as 2013, some observers argued that this was the result of a maturing market (Church and Wilkins, 2013, p. 40), but this explanation is myopic and ignores the under-development of the mobile wireless market in Canada relative to all but a few of its OECD peers. In addition, the intervening years have shown this prediction to be incorrect. Although revenue continues to grow at a significant rate, adoption levels in Canada have not improved substantially, either in absolute terms or relative to our peers.

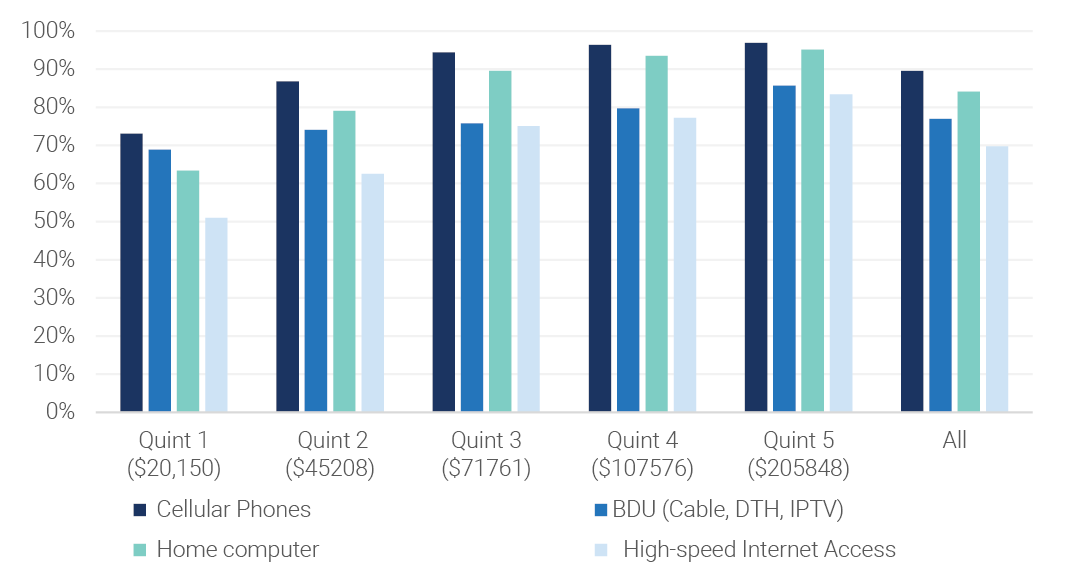

For households in the lowest income quintile, more than one-in-four do not subscribe to a mobile wireless service, while just a little over one-in-seven of those on the next rung up the income ladder stand in the same position. At the opposite end of the income scale, however, mobile wireless penetration is nearly universal at 97%. Figure 6 illustrates the levels of adoption for mobile phones by income quintiles in Canada as of 2017 (which is, unfortunately, still the most recent data from Statistics Canada), as well as for broadband Internet, home computers and cable television.

Figure 6: Household Adoption to Information and Communication Technologies by Income Quintile, 2017

Source: Statistics Canada (2019). Dwelling characteristics, by household income quintile in Canada. In Statistics Canada, 2018. Survey of Household Spending.

In the past, Rogers, Bell, Telus, and other observers who are content to serve “economic” customers (while ignoring those who struggle to afford access to this crucial service) have attempted to distract attention from these low levels of penetration by touting the supposedly large number of subscribers who have smartphones. However, as the OECD data presented above show, adoption of mobile broadband services in Canada—smartphone connectivity, that is—remains woefully low by international standards (OECD, 2019).

Canada does not fare well in terms of mobile data usage either, ranking 31st out of 35 OECD countries for which data was available last year. With an average of 2.9 GB of mobile data usage per subscriber per month last year, Canada was well below the OECD average of 5.8 GB per month, and dramatically behind usage levels in countries such as Finland (23.5 GB, the leader), Austria (19.1 GB), Denmark (9.6 GB) Sweden (8.9 GB) and considerably less than in France (7.7 GB), as well as the UK (4.1 GB) and Australia (7.6 GB) (OECD, 2019).

There are many reasons for this state of affairs, but price and affordability are certainly two key considerations (OECD, 2018; Klass & Winseck, 2019). The concentrated structure of mobile wireless markets and diagonally-integrated nature of the firms that operate in them are also key factors. Incoherent policies and inconsistent actions by the CRTC, Competition Bureau and ISED/Industry Canada also contribute greatly to this state of affairs (see Middleton, 2017 and Benkler, et. al. 2009). At present, the CRTC is undertaking a review of its policies directed toward the mobile wireless sector, with a specific focus on determining whether current levels of competition are sufficient to serve the interests of users. The above adoption and usage data suggest that they are not; we, along with many others in Canada, anxiously await the result of this consultation.

While wireless services now occupy the centre of the media universe, the wireline telecoms infrastructure that supports plain old telephone service (POTS), value-added business services, internet access, cable and IPTV networks continues in its place as a pillar in the network media economy. Combined, these services accounted for over half of all telecoms and internet access revenues (50.6%) in 2018, while mobile wireless services accounted for the rest.

On its own, however, plain old telephone service revenue fell to $13.4 billion last year—far off the high-water mark of $21.2 billion in 2000, but with the steep drop-off flattening out in recent years. Those decreases, however, have been offset by gains in internet access, IPTV and cable revenues. Most of the telecoms and cable companies such as Bell, Telus, Rogers, Shaw, Quebecor and Cogeco were also acquiring data centre operations in the early part of this decade but in the past few years, the latter three have reversed course and sold off their data centres to firms specializing in cloud computing. More recently, some firms have moved into the provision of specialized services; for instance Telus has begun to offer healthcare-related services accounted for within the ambit of its wireline division. The lack of available disaggregated data does not allow us to gauge the scale of these activities with any precision, but it is worth noting that they may be coming to play an increasing role in the wireline activities of major Canadian telecommunication companies.

Internet access revenues have grown immensely in the past decade, similar to mobile wireless. Internet access revenues were roughly $12.7 billion last year, up from $11.8 billion the previous year, and more than six times what they were at the turn-of-the-21st century ($1.8 billion). The adoption of wireline Internet access in Canada is high relative to other OECD countries, but so too are prices, while available speeds are mediocre, household data use comparatively low (192 GB per household per month in 2018), and data caps commonplace, whereas in most comparable countries they are rare and overage charges not nearly as punishingly expensive (OECD, 2018; FCC, 2017; ITU, 2018; Cisco, 2017).

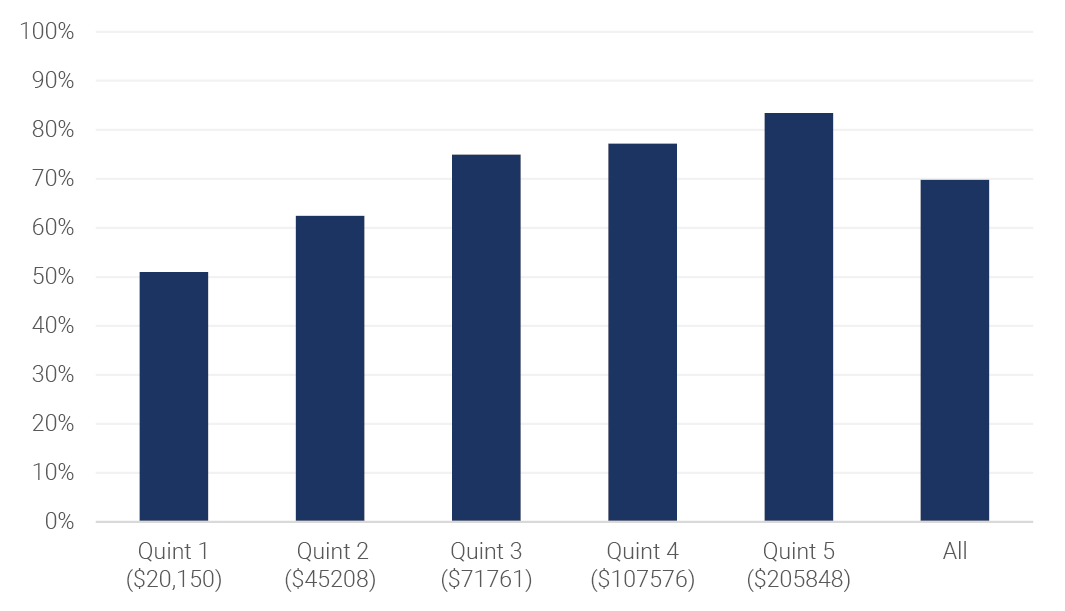

Also, like mobile wireless services, high-speed and broadband Internet access are far from universal. According to Statistics Canada’s most recent data (2017), 86% of households have adopted high-speed internet access service (i.e. > 1.5 Mbps). If we consider the uptake of services that meet the broadband universal service target of 50 Mbps up and 10 Mbps down adopted by the CRTC in 2016, half of Canadian households met that target in 2018 (CRTC, CMR 2019, p. 255). There are also significant disparities in access between urban versus rural and remote areas, and people’s adoption of broadband is divided starkly along income lines as well. Figure 7 below illustrates the point.

Figure 7: High-Speed Internet Adoption by Income Quintile, 2017

Source: Statistics Canada (2019). Dwelling characteristics, by household income quintile in Canada. In Statistics Canada, 2019. Survey of Household Spending.

A key development over the past decade-and-a-half has been the growth of the telephone companies’ (e.g. Telus, Bell, SaskTel) Internet Protocol TV (IPTV) services. This took place slowly at first but since 2010 the pace of IPTV development has quickened. By the end of last year, the incumbent telcos’ managed Internet-based television services had over 3 million subscribers between them. As a result, the telco’s IPTV services now compete extensively with traditional cable television services in cities across the country. Figure 8 below shows the growth in IPTV subscribers over the past decade-and-a-half.

Figure 8: The Growth of IPTV Subscribers in Canada, 2004-2019

Source: see the “IPTV” data sheet in the Excel Workbook.

The telcos’ revenue from IPTV service has also increased sharply from $1 billion in 2013 to nearly $2.1 billion last year–again, nearly double the amount six years earlier. Figure 9 below shows the trends.

Figure 9: The Growth of IPTV Revenues in Canada, 2004-2019

Source: see the “IPTV” data sheet in the Excel Workbook.

The addition of IPTV as a new television distribution platform has brought the telecoms operators deeper into the cable companies’ traditional turf. MTS, SaskTel and Telus first began to deploy IPTV in the prairie and western provinces in the mid-2000s, with Bell only following suit in the early 2010s, perhaps because it did not want to cannibalize its direct-to-home satellite television service. Fast forward to 2019, and the number of IPTV subscribers and revenue have grown considerably, accounting for over a quarter of the TV distribution market. Moreover, the fact that telecoms operators’ IPTV services have gained market share at the same time that “cord cutting” has picked up steam in the past five years has significantly added to the competitive pressure that the cable companies now face from the telcos’ IPTV services.

Figure 10 below illustrates these points.

Figure 10: Cable & Satellite Provider vs IPTV Revenues, 1984-2019 (current $, millions)

Sources: see the “IPTV” and “CableSatIPTV” data sheets in the Excel Workbook.

As Figure 10 also shows, cord cutting—the process whereby people drop their cable, IPTV or DTH service in favour of accessing audiovisual media services directly over the Internet (or over the air, or not at all)—has gained traction over the past five years. Thus, even though IPTV has grown substantially over the past decade, the number of subscribers for all broadcast distribution undertakings (BDUs as they are called in Canadian regulatory parlance) has slipped from 85.6% of households at its highpoint in 2011 to 75% last year. In short, the phenomenon of cord-cutting is real.

The loss in BDU subscribers that has taken place, however, has resulted only in modest revenue losses to the BDU sector; revenue fell from $8.9 billion in 2014 to $8.2 billion last year—a decline of 7%. This is largely because at the same time that cable subscribers were starting to cut the cord there have been steep increases in subscription prices for BDU services. Crucially, just as people have turned to access online subscription-based and download AVMS directly in lieu of a cable subscription, the price of Internet access has also jumped. In fact, the price of subscriptions for cable TV and Internet access have risen well above increases in the consumer price index, as Figure 11 below illustrates. The sharp rise in Internet access prices since 2010-2011, just as cord cutting was starting to cut into the cable operators’ revenues, is especially noteworthy.[8]

Figure 11: The Price of Communication Services and Devices vs the Consumer Price Index, 2002-2019

IPTV services are also critically important because they are the cornerstone of the telecoms operators’ efforts to bring next generation, fiber-based Internet networks closer to subscribers, mostly to neighbourhood nodes and increasingly to people’s doorsteps. In fact, the distribution of television and entertainment services are critical to driving the demand, and thus the revenue, that the telecoms operators need to invest in bringing next generation fibre optic broadband networks to people’s doorsteps (see below).

The rate of IPTV adoption in Canada has been relatively high by international standards. Just over 20% of households in Canada subscribed to IPTV services in 2019. While comparable international data for 2019 is not publicly available, this level of IPTV adoption is comparable to adoption levels for 2016 in Spain (where uptake of IPTV reached 20% of households), China (where it was 21%) and Sweden (17%) but well above the US (9%), Japan (8%), Germany (6%), the UK (7%) and Australia (7%). However, IPTV uptake in Canada still lags far behind where adoption levels were as of 2016 in France (40%), Korea (32%) and the Netherlands (30%) (Ofcom, 2017 p. 106).

While Canada has done fairly well with respect to IPTV availability and adoption, the picture changes for fiber-to-the-premise/doorstep (FTTP), which, as Susan Crawford (2019) observes, represents the gold standard of telecommunications networks, and will be a requirement for future economic growth. Indeed, just 17.2% of broadband connections in Canada use FTTP compared to the OECD average of 28%. At the high end of the scale, in Norway, Finland, Sweden, Japan and Korea, one-half to four-fifths of all broadband connections are fiber-based. According to the OECD, Canada ranked 26th out of 36 countries on this measure as of December 2019. Figure 12 below illustrates the point.

Figure 12: Percentage of Fibre Connections Out of Total Broadband Subscriptions (December 2019)

Source: OECD (2020). Broadband Portal, Table 1.10.

In sum, when it comes to fibre-optic networks, the prairie telcos and Telus were the first do deply them in the mid-2000s while Bell only began to do so in a substantial way after 2010. Globally, Bell’s late turn to IPTV and FTTP in Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Provinces means that Canada continues to lag significantly behind comparable countries on this measure.

The general evolutionary pattern that we see replays a long-standing practice for new services to start out as luxuries for the rich before a combination of competitive markets, public pressures and public policies turn them into affordable necessities for people at large (see Richard John with respect to the US history, Robert Babe for Canada). Current debates over access to broadband infrastructure are the latest iteration of this old story (Winseck Reconvergence, Winseck and Pike, John, Babe, Middleton). In fact, this could be seen at the end of 2016, when the CRTC set new standards for universal and affordable broadband Internet service: minimum speeds of 50 Mbps up and 10 Mbps down to 90% of the population by 2021 (and the rest of the country a decade to a decade-and-a-half later), and with an unlimited option on offer—that is, an Internet connection with no data cap. While the idea of unlimited Internet service was the norm in Canada before 2010, and remains so for most people in the developed world, today it is just one available options amongst others and expensive in Canada. Policymakers have recognized that access to the Internet is no longer a luxury, and this has been made especially clear during the Covid-19 pandemic of 2020, large strides will be needed to ensure that aspirations meet the reality on the ground, as Canada’s standing with respect to deployment and adoption of fibre-to-the-doorstep reminds us.

A similar relatively large view of the public’s interests was pursued in early 2017 under the previous CRTC chair when the regulator adopted new rules that stop the telcos and ISPs from using zero-rating to pick and choose some services, apps and content that won’t count against subscribers’ monthly mobile wireless data caps while everything else does. While zero-rating can be attractive to the companies as a way to differentiate their services from those of competitors, and to some consumers who see this as way of getting data for “free”, such practices are better seen as marketing gimmicks propped up by artificially low data gaps and limited choices. In places where data caps are large or non-existent, zero-rating is rarely used, whereas in countries where they are low, like Canada, it is far more common—at least until the CRTC’s ruling that effectively banned it.

While mobile wireless markets tend to be highly concentrated wherever one looks around the world, it is the absence of stand-alone mobile network operators and maverick firms—a case that fits Canada—where data caps tend to be the lowest and the most extensively used. This phenomenon is further aggravated in contexts where telephone companies also own TV and entertainment services, as is in Canada, because under circumstances where vertical integration is the norm, carriers have both the incentive and the ability to zero-rate their own services while counting everything else towards subscribers’ monthly data allowance. In other words, several structural features of broadband and mobile wireless markets in Canada bias them toward low and restrictive data caps and pressure from service providers to adopt “zero-rating” as an alternative to giving subscribers bigger data allowances, or even making unlimited services the norm rather than an expensive and rare option (see, for example, Rewheel/Digital Fuel Monitor, 2018).

Ultimately, questions about zero-rating embody a philosophy of communication, one that says that when data caps are high or non-existent, people can use bandwidth to communicate, entertain, express themselves, work and do with as they want— within the limits of the law, of course. When they are low, however, what people can and cannot do with “the means of communication” at their disposal is restricted. Seen from this angle, the issues at stake are not just about prices but whether the speech and editorial rights of people, “content creators and distributors”, apps makers and service providers come first or whether those of the telephone companies and ISPs are paramount. In early 2017, the CRTC ruled in favour of the first group, and drew on the principles and history of common carriage[9] to do so (see Klass, Winseck, Nanni & McKelvey, 2016).

Both rulings—the new basic service standard and the zero-rating decisions—staked out a fairly ambitious view of what Canadians need and deserve in “the digital media age”. On the one hand, it includes affordable access to high quality communication services and gives priority to the speech and expressive rights of people, content creators, apps developers and service providers over the those who own broadband Internet access and mobile wireless networks. Consequently, people do not have to accept only what the market gives them because communication needs have been recast in a more expansive way in the light of conditions in the 21st Century.

On the other hand, the telephone companies do not like this run-of- events and have wasted no effort fighting to change it over the course of the last year. Thus far, however, their main success appears to have been only to slow down the pace of change. The ongoing reviews of the Telecommunications Act and Broadcasting Act, and the swapping out of the public interest friendly J.P. Blais for an industry insider in September 2017, however, are fraught with risk and there is already some evidence of back-peddling by the Commission.

When the new Chair of the Commission, Ian Scott, was given the reins of the CRTC he was met with skepticism but also a willingness amongst critics, reformers and public interest advocates to suspend judgement because in the recent past their early suspicions of appointees who seemed too close to industry—i.e. Tom Wheeler’s position at the helm of the FCC in the US in 2013—or too close to the government—i.e. Daniel Therrien, a former national security specialist in the Harper Government, as the head of the Office of the Privacy Commissioner a year later—ended up pursuing courses of actions that confounded early expectations, and with impressive results. That well of goodwill, however, is beginning to run dry in light of, for example:

- the new Chair’s seeming deference to industry insiders,

- the call to “harness” the internet to a model of cultural policy created over a half-century ago and maintained since, reinforced by a call from the Chair for an ISP levy in support of Canadian content (CRTC, 2018),

- the constrained basis for the Commission’s rejection of an industry proposed website blocking scheme designed to combat piracy (CRTC, 2018, TD 2018-384),

- and a seeming reluctance by the Chair to gird the CRTC’s collective spine to face the realities of persistently high levels of concentration and sky-high levels of vertical integration in key communications and media sectors that have that have not served citizens, consumers, creators or the public sphere well.

It may still be too early to render a final judgment on the current approach to policy and regulation at the CRTC. However, numerous warning signs have been sounded that should not be ignored.

Traditional and Digital Audiovisual Media Services (AVMS): From Ad-Supported Content Media to Fast Growing Subscription-based Digital Media

The remainder of this report shifts gears to examine ongoing developments in the media content sectors—also referred to as the AVMS sectors—in the context of the following four over-arching trends:

- the explosive growth of online advertising;

- the faltering growth for the rest of advertising spending across all media. Although advertising spending has remained fairly fixed relative to the size of the Canadian economy for decades, over the past decade it has fallen by about 10%, or approximately $1.5 billion per year based on the value of advertising spending last year. As a result, traditional media sectors and firms that depend primarily on advertising funding as the core of their business model are battling internet giants like Google and Facebook for a stagnant/shrinking pool of revenue;

- the core of the media economy is not advertising but a rapidly growing group of pay-per media and digital AVMS that are based primarily on subscriber fees and direct payments, although after growing rapidly for three decades, specialty and pay TV services have seen their revenue taper off since 2016.

These over-arching trends, in turn, are taken up in relation to an analysis of the following digital and traditional audiovisual media services (AVMS) that make up the content media sectors of the media economy:

- Internet advertising

- broadcast TV;

- pay and specialty TV;

- online video subscriber and download services such as Netflix, Crave, Amazon Prime Video and Illico;

- radio;

- music, including recorded music, live concerts and revenues from publishing royalties;

- online music subscription and download services such as Apple iTunes and Spotify;

- online gaming, gaming applications, game downloads or in-game purchases;

- app stores (e.g. Google Play and Apple Appstore);

- newspapers;

- magazines;

- online news.

Anchor Findings

• online advertising continues to grow rapidly, with nearly all growth captured by Google and Facebook.

• regulators must contend with the consequences of this duopoly not only in online advertising, but also to curb their ability to leverage that dominance into adjacent media sectors.

While overall advertising spending has been buffeted by unsteady economic conditions for more than a decade, the growth of online advertising has continued to surge ahead. By last year, Internet advertising revenue in Canada had reached $8.8 billion—up from $7.7 billion a year before that and worth more than four times what it had been a decade ago.

It is clear that the two biggest beneficiaries of this soaring growth have been Google and Facebook, with estimated revenue from online advertising of $4.4 billion and $2.6 billion, respectively, last year. Google single-handedly now accounts for half of the Internet advertising market, while Facebook’s share is rapidly approaching the one-third mark. Together, they controlled four-fifths of the online advertising market in Canada in 2019—up significantly from a little over two-thirds share of the market five years ago.

Moreover, a majority of the new growth in Internet advertising revenue between 2018 and 2019 ended up in their coffers, although the pace of this development was down substantially from previous years when Google and Facebook took four-out-of-five dollars in new growth. In short, the digital duopoly now stand in a league of their own and their grip on the online advertising market is tightening.

Open the lens wider to examine the adverting spending in all media, e.g. Internet, television, radio, newspapers, magazines and out-of-home—and the picture, however, becomes more complicated.

First, total advertising spending in Canada last year reached $15.6 billion, but growth remains sluggish. Yet, within the context of the much larger but sluggish overall advertising market, Google and Facebook have emerged as the two biggest recipients of advertising revenue as well, light years ahead of Bell, Shaw, Rogers, Quebecor, Postmedia, Torstar and the CBC, in that order. Google, for example, now accounts for 28% of all advertising spending in Canada, while Facebook’s share has risen rapidly to just under 17% last year.

In sum, the digital advertising behemoths had an outsized 45% stake of the advertising market last year, up from 36% two years earlier. Bell, by comparison, attracted just over 10% of all advertising spending in Canada at the time. All told, these changes have propelled Google into being the fifth largest company operating in the media economy in Canada, after Bell, Rogers, Telus and Shaw; Facebook comes seventh after Quebecor.

That said, it is essential to simultaneously grasp the quick growing influence that Google and Facebook have amassed while not overstating the scale and scope of their clout across the media landscape. In the present case, for example, while their dominance of online advertising is clear-cut, their influence on the advertising market across all media requires a more nuanced assessment.

On the one hand, there is little doubt that controlling more than a quarter of all advertising revenue in Canada gives Google enormous power over the advertising market. Google and Facebook’s combined market share of 45% points in a similar direction. On the other hand, however, the assessment is mixed when using standard indicators of market concentration. For example, using the CR4 method[10], the “total advertising market” is only modestly concentrated, with the top four firms—Google, Facebook, Bell and Shaw (Corus)—accounting for 62% of the market. However, by the lights of the HHI approach, it remains highly competitive, with the HHI score of 1272 being at the low end of the scale (see “Internet Advertising Market share, 2014-2019” and “Ad$ All Media” sheets in the Excel Workbook). We will deal more with the implications and possible responses to Google and Facebook’s lock on online advertising, and their growing influence over the advertising market writ large, and potential regulatory responses to that growing clout, in the second report in this year’s series.

Within Canada and globally, Google’s dominance of online advertising is girded by the fact that it has vertically integrated its search and online advertising functions with its own proprietary digital advertising exchange, to say nothing of the dominant position it holds in relation to mobile and desktop browsers, the Android mobile operating system, and Google Play app store (typically in duopolistic rivalry with Apple in each of these areas). The cornerstone in Google’s sprawling reach across the Internet stack, however, is the online advertising system that it has assembled through a series of acquisitions over the last decade (e.g. DoubleClick, AdMob, etc.). By assembling its own online advertising exchange, Google has, in essence, erected a walled garden around its services as well as the buying and selling of audiences on the Internet, a stark contrast from its early promise to help people navigate the ‘open Internet’ and slay the walled gardens that had emerged in the late-1990s.

While Facebook does not have its own digital advertising exchange, both it and Google share the fact that they control the common currency used to buy and sell audiences and advertising inventory on the Internet: detailed and intimate knowledge of their audiences. Each company also has its own audience measurement and rating system that allows them to control the terms of trade upon which the online advertising system functions.[11] By controlling the building blocks of the online advertising system both companies are able to effectively hold third party advertising campaigns hostage because neither of them interconnect with one another, or with other digital platforms. Consequently, advertising campaigns, and the data, costs, and labour behind them, are not portable between competing advertising exchanges, thereby allowing Google and Facebook, in effect, to use this control to hold audiences and advertisers hostage. This raises the prospect of using mandated data portability, network interoperability and interconnection obligations to put a dent in their dominance(another point we will return to in the next report).

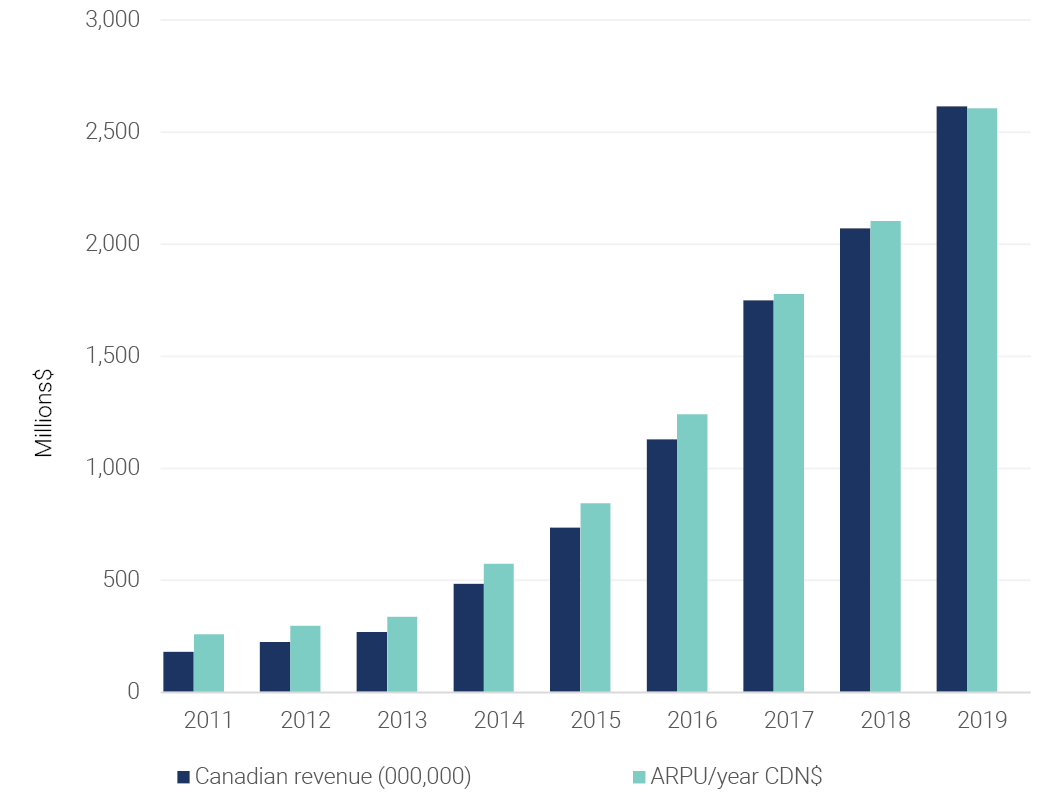

For its part, Facebook had 21.5 million users in Canada at the end of 2019 and revenue of $2,614 million. The company has benefitted in particular from the shift from “desktop Internet” to the mobile Internet. Thus, while Facebook had only a few dozen people working on the mobile Internet version of its app as late as 2012, by the end of that year it had done an about face as it set out to make the mobile Internet its new frontier of expansion. As a result, the mobile version of Facebook’s service is now the centre of the companies’ operations.

The growth rate for the number of people using the company’s three main services—Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp—in Canada has been swift, to say the least, over the past decade but it has slowed in recent years. Slowing growth in the size of Facebook’s user based has not caused revenue growth to stall, however, because the company has focused on sharply increasing the monetary value of each user. And it has succeeded at this as well. The annual average revenue per Facebook user (ARPU) in Canada last year was $121.58—double what it was three years ago and ten times what it was in 2011.[12]

Figure 13 below depicts the growth of Facebook’s revenue and ARPU in Canada since 2011.

Figure 13: Facebook’s Revenue (millions$) and Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) Soar, 2011-2019

Source: see “App Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

In sum, Google and Facebook have become major players in Canada in a short period of time. They form a duopoly in Internet advertising and the scope of their influence is growing in relation to the overall advertising market. Based on these trends, it has become an article of faith in many quarters—academic, industry, think tanks and advocacy groups, policy-makers and regulators—that Google and Facebook are primarily to blame for the existential crisis now being faced by the media in Canada. While this account of the domestic media industries being decimated by a clutch of rapacious Internet giants headquartered in Silicon Valley might seem to be compelling at first blush, it is superficial and deeply misleading.

For one, most sectors of the content media are vibrant and have grown considerably over the thirty-five years covered by our project. However, there are four exceptions to this general rule: broadcasting television, radio, newspapers and magazines, all of which rely primarily on advertising funding and have been in decline since 2008.

While advertising continues to be the most significant source of revenue for the media content sectors, it is swiftly being eclipsed by others that depend mainly on subscriber fees and direct payments. For example, revenue for specialty and pay TV services doubled in the last decade to $4.4 billion in 2016, before tapering off to $4.2 billion last year. Simultaneously, however, subscription-based and download video and music services as well as online games, apps, downloads and app stores are rapidly becoming the engines of growth across the AVMS sectors. The combined revenue for these sectors soared eight-fold from $719 million to $5.6 billion between 2011 and last year. Taken in their entirety, and in sharp contrast to the usual story, there is no general crisis of the media in Canada and the content media sectors have grown immensely over time: their revenue in 1984, was $5.6 billion; last year it was $27.7 billion.

Figure 14 below depicts the long-term growth of the content media sectors over the period covered by this project.

Figure 14: Rising Revenues for the Content Media Industries, 1984-2019 (current $, millions)

Source: see the “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Growth for nearly all content media sectors was steady, even brisk, until the financial crisis of 2008, except for several years in the early 1990s recession and again just after the collapse of the dot.com bubble at the turn-of-the-century. Since 2008, however, revenue for advertising-funded AVMS sectors have fallen sharply, while those based on subscriber fees and direct purchases have proved far more resilient and, in the vast majority of cases, have grown rapidly. These ongoing trends and patterns reflect the fact that advertising spending—and thus the fate of advertising-funded media—follows the twists and turns of the economy in lockstep fashion (see Picard, Garnham, Miege, and Vogel).

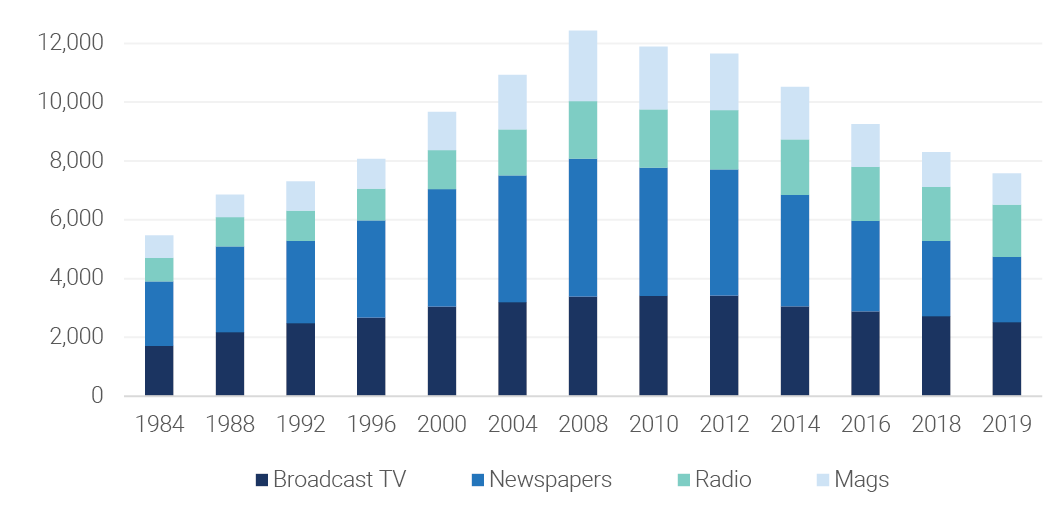

Since 2008, total advertising spending has slowed, stagnated or shrunk, in real dollar terms, relative to the size of the Canadian economy (gross domestic income), in relation to the size of the media economy and on a per capita basis. Although this trend has abated in the past two- to three years, the “lost decade” before that brought about by slumping, stagnant and/or slow advertising growth since 2008 means that $800 million to $2.3 billion in ad revenue per year has vanished relative to what it would have otherwise been had “normal” growth rates held steady—roughly a billion-and-a-half dollars per year if we split the difference.[13] Figure 15 below illustrates the wreckage.

Figure 15: The Rise and Fall of Advertising-funded Traditional Media, 1984-2019 (millions, current$)

Source: see “Media Economy” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

All told, the contraction in advertising spending has hit the four sectors of the media that have historically been the most reliant on advertising hard: broadcast television, radio, newspapers and magazines. Collectively, their revenue has plummeted by $4.9 billion since 2008. This trend is unlikely to turn around any time soon.

That the fate of advertising spending—and thus the media that rely on it—hinges on the state of the economy can be seen by tracking the ups and downs of advertising revenue since 2008. During this time, for example, advertising spending grew from $11.5 billion to $15.6 billion in nominal terms. However, almost all of that growth occurred in the last three years. Also, if you switch the metric to real dollars, the story is even grimmer; revenue hovered between $13.5 and $14 billion from 2008 to 2015 (CAGR of .44%) before slowly rising again to $15.6 billion last year (i.e. CAGR of 1.3%).

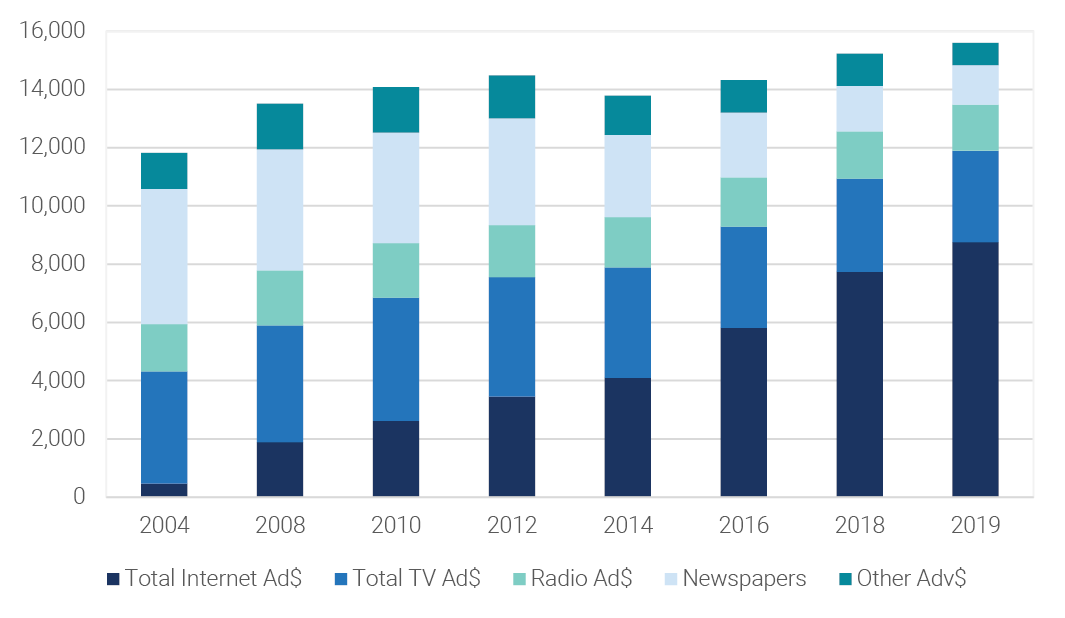

Figure 16 below reveals the period of relatively low to no growth between 2010 and 2016, and the slow increase since, as well as changes over time in terms of which media type gets how much of the advertising pie.

Figure 16: The Stagnating Advertising Economy, 2004-2019, I—Advertising Revenue for Television, the Internet and “All Media” (real $ 2019, millions)

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Looking at advertising revenue on a per capita basis (in real dollars), advertising spending fell sharply from $405.90 per person in 2008 to $388.20, then bounced around at relatively low levels for a decade, before finally returning to its previous levels in the last year or two. In 2019, advertising spending was $420.10 per capita—a painfully slow CAGR of .33% for just over a decade. In terms of advertising earmarked for television, it has slid continuously from the first decade of the 21st Century when it hovered around $110-$120 per person (in real dollars) to $84.40 per capita last year. The fortunes of Internet advertising, of course, have run in exactly the opposite direction, quadrupling from $57 per person in 2008 to $233 last year. Figure 17 below depicts these points.

Figure 17: A Ceiling for Ad Spending?: Advertising Spend per Capita, 2004-2019 (real $ 2019)

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

Figures 18 below also reveals a pattern of stagnating or shrinking advertising spending relative to the size of the network media economy over the last decade. In this case, advertising spending levels remain lower today than they were a decade ago.

Figure 18: Ad Spend as a Percentage of the Network Media Economy, 2004-2019

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

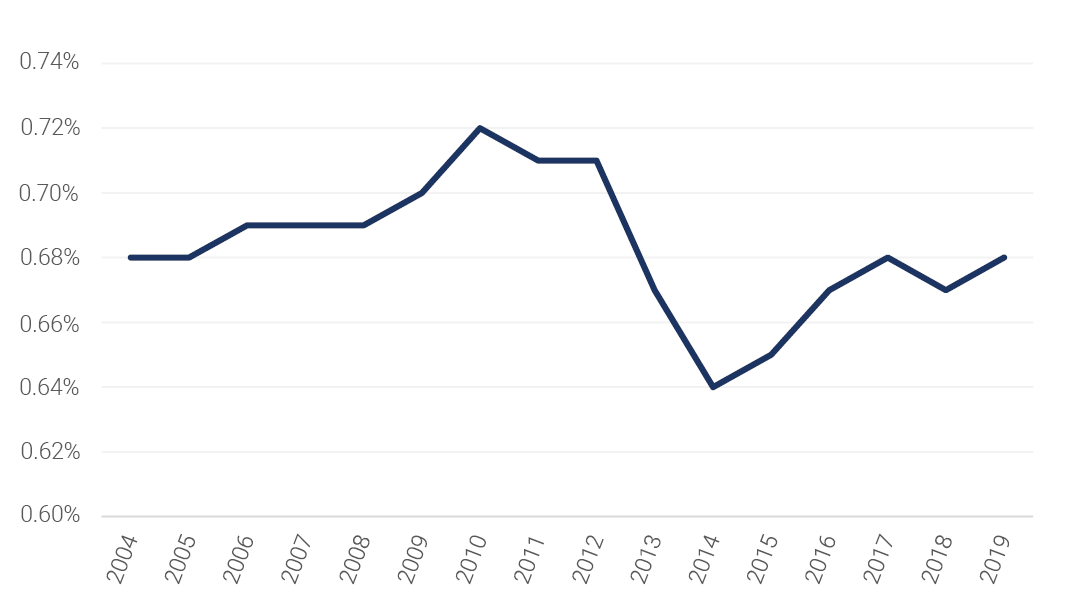

The downward pressure on advertising can also be seen in terms of GDI, as shown in Figure 19 below. Historically, advertising spending as a portion of the Canadian economy has stayed relatively fixed at roughly .68 to .7% of gross domestic income (GDI), a rate, incidentally, that is significantly lower than in the United States, probably serving as an index of the less commercialized character of the media and society in Canada relative to the US. In 2019, however, after nearly a decade of anemic and unsteady economic growth, this measure, too, still sat at the lower ends of that range.

Figure 19: Ad Spending as a Percentage of Canadian Gross Domestic Income, 2004-2019

Source: see the “Ad$ All Media” sheet in the Excel Workbook.

The upshot of these observations cannot be understated. While Google and Facebook are undoubtedly implicated in the dire situation faced by those media sectors and firms that rely primarily on advertising revenue as the centre of their business models, they are not the primary cause of it.

Instead, the situation reflects a confluence of structural conditions stemming from the state of the economy as well as self-inflicted wounds incurred over a quarter-of-a-century of excessive mergers and acquisitions that have since taken their toll (see the next report for more detail). To date, however, those who blame Google and Facebook for stealing away ad revenue from media companies in Canada—and precipitating a “crisis of the media”—have had nothing to say about these other deeper and broader forces, preferring to focus the blame on a convenient scapegoat—the “Web Giants”—instead.

Anchor Findings

• Broadcast television has been in decline since 2011.

• After several decades of strong growth, specialty and pay television services have also seen revenue slip since 2016.

• Rather than cannibalizing existing revenues, online video services have substantially grown the market for audiovisual media content in Canada.

• Canada’s film and television production industry has seen record high investment in new productions in the past several years, with investment levels in 2019 nearly double what they were a decade ago.

• The integration of broadcasting and pay television industries with one another—and into the operations of the country’s largest telecoms operators—is unique to Canada and may have dampened competitive pressure and reduced their ability to respond to market developments and broader shifts in AVMS, as seen in other international markets.

Advertising for broadcast television grew more or less steadily until reaching a high point of $2.5 billion in 2010 and 2011. Despite suffering the initial shock of the 2008 financial crisis like the rest of the commercial media, advertising revenue for broadcast television rebounded for the next few years but the reprieve was short-lived. Despite some fluctuations along the way, advertising spending on broadcast television has dropped from $2.5 billion in 2011 to $1.8 billion last year. The shift of some advertising dollars to specialty cable and satellite channels such as Discovery, TSN, RSN, the Cartoon Network, etc. has helped to recover some of the slack, but overall advertising across the total TV landscape has declined from a high of $3.8 billion in 2011 to $3.1 billion last year.

We see similar trends playing out in the radio sector, where revenues peaked in 2011, at $2,016 million (including the CBC’s parliamentary appropriation). They have fallen slowly but steadily since, reaching $1,779 million last year (current dollars).

Cut-backs by the previous Conservative Government to the CBC of $126 million after 2012, and the loss of $121.1 million in payments from the Local Program Improvement Fund after 2013 until it was phased out completely by 2015, further compounded the woes facing the CBC and broadcast television stations earlier this decade (see the CBC, Annual Reports and the CRTC, CBC Aggregate Annual Return French and English for these years).

Overall broadcast TV revenues, including the CBC and its annual Parliamentary funding, slid from an all-time high in 2011 of $3,501.7 million to $2,518.6 million last year—a 28% decline. As a result of these trends, eight local TV stations have been shuttered since 2009: CHCA (Red Deer), CKNX (Midwest ON), CKX (Brandon), Sun News (Toronto), three of Rogers Omni affiliates in BC, Alberta and Ontario, and another station in Kenora that was closed by Shaw in 2017 (Lindgren & Corbett, 2020).

Alongside these trends, job lay-offs and cut-backs have become a constant theme. Between 2012 and 2015, for example, local news staff at broadcast TV stations was cut by 4%, according to Colette Brin’s contribution to the Reuters Institute’s 2016 Digital News Report (p. 80).[14]

A study prepared for the Friends of Canadian Broadcasting and Unifor by Peter Miller (2015) estimated that half the local TV stations in fifty-six small and mid-size cities across Canada, and an additional 900 jobs, could be lost by 2020 if the major policy changes advocated by the report were not adopted (pp. 14-15). While such outcomes would decimate local broadcasting if they came to pass, we have reached the date of that dire scenario and can say that the report’s predictions have not come to pass. This outcome, in turn, serves as a reminder that ongoing tallies of job losses as well as predictions from lobby groups and hired consultants along the lines just reviewed are often sensationalist and wide of their mark.

Conditions have been severe enough, however, to have spawned two reviews in 2016 of the state of local news and journalism in communities, one by the Canadian Heritage Parliamentary Committee and another by the CRTC. Both reviews added further insights into the situation but ultimately struggled to come up with workable solutions to the problems at hand. That said, they were part and parcel of broad ranging efforts in many quarters that led the Liberal Government later that year to add $675 million to the CBC’s annual funding envelope spread out over the next five years. While these new funds countered the cuts to the CBC undertaken by the previous government, they do not come close to offsetting the decline in advertising revenue at the CBC.

In sum, four points help to explain the stagnation and decline of broadcast TV over the last decade:

- declining advertising revenue since 2011;

- budget cuts to the CBC;

- the phasing out of the Local Program Improvement Fund between 2012 and 2015;

- the big four commercial TV providers – Shaw, Bell, Rogers and Quebecor – shift of resources from their broadcast TV holdings to the vast stable of pay, specialty and other subscriber-based TV services that they own (i.e. mobile, IPTV) (see the CRTC’s Individual Financial Summaries for a list of the 105 pay and specialty services the big four combined owned as of 2019).

While the dire condition of broadcast TV in Canada is obvious, a crucial question remains as to why things are so poor relative to conditions in the US and some other countries? To put this another way, while broadcast TV is not thriving anywhere, the turmoil in Canada is especially severe. Why?

While we must be cautious about identifying any one cause for the dramatically different situations in Canada versus the US (and elsewhere), one key difference stands out: broadcast TV providers in the US (and elsewhere) are not nearly as integrated into the telecoms-Internet sectors and specialty and pay TV services as they are in Canada (a point that will be taken up in greater detail in the second report of our annual series). In fact, broadcast TV ownership groups in the US are sizeable, independent entities in their own right, unlike Canada—where all of the biggest commercial broadcast TV as well as pay and specialty TV services are owned by one and the same players, e.g. Bell, Shaw (Corus), Rogers and Quebecor (see FCC, 2018, para 90). Other than Comcast’s ownership of NBC Universal, for example, none of the main broadcast TV ownership groups in the US have been owned by telecoms companies or BDUs (although this changed somewhat after AT&T’s take-over of a raft of pay television services, including HBO, when it acquired Time Warner in 2018) (see FCC, 2018, para 67).

Yet, even accounting for AT&T’s acquisition of Time Warner in 2018, Canada still stands alone from its international peers in terms of its extraordinarily high levels of diagonal and vertical integration across the entirety of the network media economy (for a fuller elaboration of this claim, see CMCRP, 2016). Despite this, the current chair of the CRTC acknowledges the high levels of vertical integration in Canada but appears to take a sanguine view of such matters when he, incorrectly, asserts that “this trend toward vertical integration was not unique to Canada” (Scott, 2019).

The existence of separate broadcast TV and pay TV ownership groups in the US creates conditions that drive them to compete head-on with one another rather than to function as arms of the telecoms giants that then operate with one eye fixed on their rivals and the other on ensuring that whatever competitive strategies they adopt do not side-swipe other aspects of their vertically and diagonally-integrated telecoms-Internet and TV operations. Conditions similar to those in the US also hold true in Europe.

Second, because of their independent ownership, stand-alone broadcast TV services in the US compete vigorously with specialty and pay TV services as well as online video rivals like Netflix, Hulu, CBS All Access, Disney+, Viacom-owned PlutoTV and Amazon Prime. Indeed, big broadcast groups in the US are sizeable entities in their own right; notable examples include CBS, Sinclair, TEGNA, Comcast, E.W. Scripps, Gray, Nexstar, Univision, Walt Disney, Fox, and Media General. Other than Disney (the ABC network) and Fox, however, broadcast TV ownership groups tend not to also own a fleet of specialty and pay TV services – again, unlike Canada—where all of the large commercial broadcast TV as well as pay and specialty TV services are owned by one and the same players, e.g. Bell, Shaw (Corus), Rogers and Quebecor.

Consequently, the US broadcasters are more eager to exploit the opportunities of putting their programming online to allow audiences to watch programs from anywhere using any device and to engage in “catch-up” viewing outside the constraints of the over-the-air broadcast schedule than their Canadian counterparts. Putting programming online also opens a new line of advertising revenue that they have exploited to far greater extent than Canadian broadcasters. As a result, online advertising has contributed more to the bottom line of broadcast television stations in the US than in Canada, growing from 5% of their revenue in 2012 to 8% in 2017 (FCC, 2017, para 119; (see FCC, 2018, para. 101). By contrast, online advertising revenue for television services in Canada lags considerably, rising from 3.2% in 2012 to 6% in 2019 (see the Ad$ All Media sheet in the Excel workbook).

In other words, common ownership of distribution and broadcast services has taken significant sources of revenue off the table for broadcasters in Canada. This has no doubt contributed to the severity of their woes. Yet, once again, instead of considering these self-induced structural sources of the plight of broadcasting in Canada, however, most observers are content to blame the Internet, GAFAM and Netflix.

In addition, as a result of their structural independence,[15] broadcast TV ownership groups in other countries are compelled to compete vigorously on their own—they sink or swim on the merits of their service offerings. Unlike their Canadian counterparts, they have no integrated or affiliated operations in adjacent markets to fall back on or strategically consider. The results of this dynamic can be seen, for instance, in the fact that the number of US households that are broadcast-only has steadily risen in recent years, from 10% in 2015 to 13% in 2017 (see FCC, 2016; FCC, 2018, para 109). Broadcast network affiliates’ and independent TV stations’ “total day share of viewing” has also increased from 30% in the 2012-2013 to 33% in the 2015-2016 season, while prime time viewing rose from 33% to 36% over the same period. Overall, broadcast TV revenue in the US rose from $24.3 billion in 2013 to $30.7 billion in 2017 as well (see FCC, 2018, para. 101; FCC, 2017, paras 116-119; FCC, 2016, paras 116-119).

For all the woes affecting broadcast TV, the overall TV universe continues to expand and to offer people a richer and more diverse range of choices. Looking beyond the Cassandra calls of industry-friendly policy rhetoric, one quickly discovers vibrant, new centres of development, while established operators are forced to adapt to changes in technology, the structure of markets, and how people watch and use television. As has been emphasized throughout this report, the real growth in television has been in subscriber fees and the pay-per and internet-based streaming and download audiovisual media services—a case that it is just as true in Canada as it is in many countries around the world.

The UK regulator, Ofcom, underscores the point: “Subscription revenues [worldwide] continue to be the key driver of this growth, rising by 5.4% to reach £125bn, just over half of total revenue”, and a cumulative annual growth rate of 5.3% over the last five years (Ofcom, 2015, pp. 139-141). As Ofcom’s (2017) most recent report observes, “Pay TV remains the largest source of TV revenue across comparators” (p. 97). The same applies to Canada.